Anyone who has attended a food safety conference in the last few years has experienced some type of whole genome sequencing (WGS) presentation. WGS is the next big thing for food safety. The technology has been adopted by regulatory agencies, academics, and some food companies. A lot has been said, but there are still some questions regarding the implementation and ramifications of WGS in the food processing environment.

There are a few key acronyms to understand the aspects of genomics in food safety (See Table I below).

| PFGE | Pulse Field Gel Electrophoresis | Technique using restriction enzymes and DNA fragment separation via an electronic field for creation of a bacterial isolate DNA fingerprint; PFGE is being replaced by WGS at CDC and other public health laboratories |

| WGS | Whole Genome Sequencing | The general term used for sequencing—a misnomer—the entirety of the genome is not used, and depends on the analytical methodology implemented |

| NGS | Next Generation Sequencing | NGS is the next set of technology to do WGS and other genomic applications |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms | A variation in a single nucleotide that occurs in specific position of an organism’s genome; Used in WGS as a methodology for determining genetic sameness between organisms |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing | A methodology for determining genetic sameness between organisms; Compares internal fragment DNA sequences from multiple housekeeping genes |

| 16S | 16s RNA sequencing | A highly conserved region of the bacterial genome used for species and strain identification |

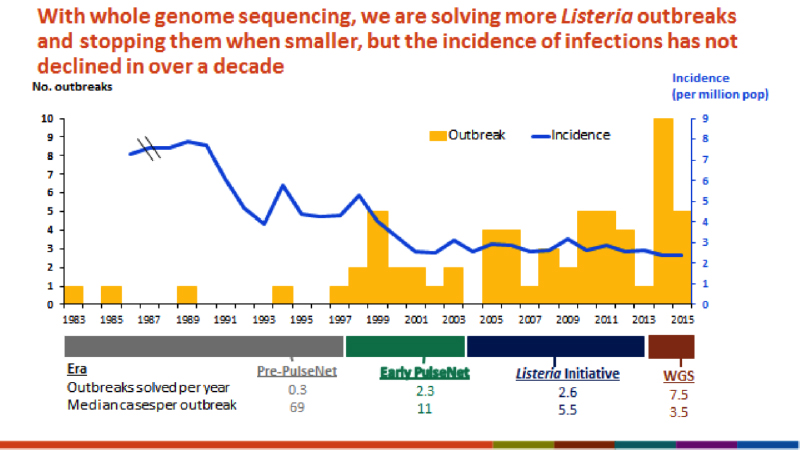

Joseph Heinzelmann will be presenting: Listeria Testing Platforms: Old School Technology vs New Innovative Technology during the 2016 Food Safety Consortium | LEARN MOREIn 1996, the CDC established the PulseNet program for investigating potential foodborne illness outbreaks. PulseNet has relied on using bacterial DNA fingerprints generated via PFGE as comparisons for mapping potential sources and spread of the outbreaks. Due to a number of advantages over PFGE, WGS is quickly becoming the preferred method for organism identification and comparison. Moving to WGS has two critical improvements over PFGE: accuracy and relatedness interpretation. Like PFGE there are nuances when defining the difference between two very closely related organisms. However, instead of defining restriction enzymes and comparing the number of bands, the language changes to either single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) or the number of alleles. The other important aspect WGS improves is the ability to determine and interpret the relatedness of organisms more broadly. The frequent Listeria outbreaks and incidence from 1983-2015 provide an insight to what the future might hold with WGS implementation.1 The incidence report shows the increased ability to quickly and more accurately define relatedness between clinical cases creates a link of potential cases much faster.

WGS also provides key practical changes for outbreaks and recalls in the food industry. Sequencing provides a much faster response time and therefore means the outbreaks of foodborne illness decrease, as does the number of cases in each outbreak. As the resolution of the outbreaks increases, the number of outbreaks identified increases. The actual number of outbreaks has likely not increased, but the reported number of outbreaks will increase due increased resolution of the analytical method.

WGS continues to establish itself as the go-to technology for the food safety agencies. For example, the USDA food safety inspection service recently published the FY2017–2021 goals. The first bullet point under modernizing inspection systems, policies and the use of scientific approaches is the implementation of in-field screening and whole genome sequencing for outbreak expediency.

Agencies and Adoption

The success of FDA and CDC Listeria project provides a foundation for implementation of WGS for outbreak investigations. The three agencies adopting WGS for outbreak investigations and as replacement for PulseNet are the CDC, FDA and USDA. However, there are still questions on the part of the FDA for when WGS is utilized, including under what circumstances and instances the data will be used.

In recent public forums, the FDA has acknowledged that there are situations when a recall would be a potential solution based on WGS results in the absence of any clinical cases.2 One critical question that still exists in spite of the public presentations and published articles is a clear definitions of when WGS surveillance data will be used for recall purposes, and what type of supporting documentation a facility would need to provide to prove that it had adequate controls in place.

A key element is the definition between agencies for sameness or genetic distance. The FDA and FSIS are using a SNP approach. A sequence is generated from a bacterial isolate, then compared with a known clinical case, or a suspected strain, and the number of different SNPs determines if the strains are identical. The CDC is using the Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) approach.

Simple sequence comparisons are unfortunately not alone sufficient for sameness determination, as various metabolic, taxa specific and environmental parameters must also be considered. Stressful environments and growth rates have significant impact on how quickly SNPs can occur. The three primary pathogens being examined by WGS have very different genetic makeups. Listeria monocytogenes has a relatively conserved genomic taxa, typically associated with cooler environments, and is gram positive. Listeria monocytogenes has a doubling time of 45–60 minutes under enrichment conditions.3 These are contrasted with E. coli O157:H7, a gram negative bacteria, associated with higher growth rates and higher horizontal gene transfer mechanisms. For example, in an examination of E. coli O104, and in research conducted by the University in Madurai, it showed 38 horizontal gene elements.4

These two contrasting examples demonstrate the complexity of the genetic distance question. It demonstrates a need for specific definitions for sameness within a microbiological taxa, and with potential qualifiers based on the environment and potential genetic event triggers. The definitions around SNPs and alleles that define how closely related a Listeria monocytogenes in a cold facility should be vastly different from an E. coli from a warm environment, under more suitable growth conditions. Another element of interest, but largely unexplored is convergent evolution. In a given environment, with similar conditions, what is the probability of two different organisms converging on a nearly identical genome, and how long would it take?

MLST vs. SNP

As previously stated, the three agencies have chosen different approaches for the analytical methodology: MLST for CDC and SNP of the FDA and USDA. For clarity, both analytical approaches have demonstrated superiority over the incumbent PFGE mythology. MLST does rely on an existing database for allele comparison. A SNP based approach is supported by a database, but is often used in defining genetic distance specifically between two isolates. Both approaches can help build phylogenetic trees.

There are tradeoffs with both approaches. There is a higher requirement for processing and bioinformatics capabilities when using a SNP based approach. However, the resolution between organisms and large groups of organisms is meaningful using SNP comparison. The key take away is MLST uses a gene-to-gene comparison, and the SNP approach is gene agnostic. As mentioned in Table 1, both approaches do not use every A, T, C, and G in the analytical comparisons. Whole genome sequencing in this context is a misnomer, because not every gene is used in either analysis.

Commercial Applications

Utilizing WGS for companies as a preventive measure is still being developed. GenomeTrakr has been established as the data repository for sequenced isolates from the FDA, USDA, CDC and public health labs. The data is housed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The database contains more than 71,000 isolates and has been used in surveillance and outbreak investigations. There is a current gap between on premise bioinformatics and using GenomeTrakr.

The FDA has stated there are examples where isolates found in a processing facility would help support a recall in the absence of epidemiological evidence, and companies are waiting on clarification before adopting GenomeTrakr as a routine analysis tool. However, services like NeoSeek, a genomic test service by Neogen Corp. are an alternative to public gene databases like GenomeTrakr. In addition to trouble shooting events with WGS, NeoSeek provides services such as spoilage microorganism ID and source tracking, pathogen point source tracking. Using next generation sequencing, a private database, and applications such as 16s metagenomic analysis, phylogenetic tree generation, and identification programs with NeoSeek, companies can answer critical food safety and food quality questions.

References

- Carleton, H.A. and Gerner-Smidt, P. (2016). Whole-Genome Sequencing Is Taking over Foodborne Disease Surveillance. Microbe. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/pdf/wgs-in-public-health-carleton-microbe-2016.pdf.

- Institute for Food Safety and Health. IFSH Whole Genome Sequencing for Food Safety Symposium. September 28–30, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.ifsh.iit.edu/sites/ifsh/files/departments/ifsh/pdfs/wgs_symposium_agenda_071416.pdf.

- Jones, G.S. and D’Orazio, S.E.F. (2013). Listeria monocytogenes: Cultivation and Laboratory Maintenance. Curr Proto Microbiol. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3920655/.

- Inderscience Publishers. “Horizontal gene transfer in E. coli.” ScienceDaily, 19 May 2015.

- Gerner-Smidt, P. (2016). Public Health Food Safety Applications for Whole Genome Sequencing. 4th Asia-Pacific International Food Safety Conference. Retrieved from http://ilsisea-region.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2016/10/Session-2_2-Peter-Gerner-Smidt.pdf.