Food production facilities are facing greater scrutiny from both the public and the government to provide safe foods. FSMA is being rolled out now, with new regulations in place for large corporations, and compliance deadlines for small businesses coming up quickly. Coverage of food recalls is growing in the era of social media. Large fines and legal prosecution for food safety issues is becoming more commonplace. Improved detection methods are finding more organisms than ever before. Technologies such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) can be used to track organisms back to their source. PFGE essentially codes the DNA fingerprint of an organism. Using this technology, bacterial isolates can be recovered and compared between sick people, contaminated food, and the places where food is produced. Using the national laboratory network PulseNet, foodborne illness cases can be tracked back to the production facility or field where the contamination originated. With these newer technologies, it has been shown that some pathogens keep “coming back” to cause new outbreaks. In reality, it’s not that the same strain of microorganism came back, it’s that it was never fully eradicated from the facility in the first place. Advances in environmental monitoring and microbial sampling have brought to light the shortcomings of sanitation methods being used within the food industry. In order to keep up with the advances in environmental monitoring, sanitation programs must also evolve to mitigate the increased liability that FSMA is creating for food manufacturers.

Paul Lorcheim of ClorDiSys Solutions will be speaking on a panel of Listeria Detection & Control during the 2016 Food Safety Consortium, December 8 | LEARN MOREPersistent Bacteria

Bacteria and other microorganisms are able to survive long periods of time and become reintroduced to production facilities in a variety of ways. Sometimes construction or renovation within the facility causes contamination. In 2008, Malt-O-Meal recalled its unsweetened Puffed Rice and Puffed Wheat cereals after finding Salmonella Agona during routine testing of its production plant. Further testing confirmed that the Salmonella Agona found had the same PFGE pattern as an outbreak originating from the same facility 10 years earlier in 1998. This dormant period is one of the longest witnessed within the food industry. The Salmonella was found to be originating from the cement floor, which had been sealed over rather than fully eliminated. This strategy worked well until the contamination was forgotten and a renovation project required drilling into the floor. The construction agitated and released the pathogen back into the production area and eventually contaminated the cereal product. While accidental, the new food safety landscape looks to treat such recurring contaminations with harsher penalties.

One of the most discussed and documented cases of recurring contamination involves ConAgra’s Peter Pan peanut butter brand. In 2006 and 2007, batches of Peter Pan peanut butter produced in Sylvester, GA were contaminated with Salmonella and shipped out and sold to consumers nationwide. The resulting outbreak caused more than 700 reported cases of Salmonellosis with many more going unreported. Microbial sampling determined that the 2006 contamination resulted from the same strain of Salmonella Tennessee that was found in the plant and its finished product in 2004. While possible sources of the contamination were identified in 2004, the corrective actions were not all completed before the 2006–2007 outbreak occurred. Because of the circumstances surrounding the incomplete corrective actions, ConAgra was held liable for the contamination and outbreak. A settlement was reached in 2015, resulting in a guilty plea to charges of “the introduction into interstate commerce of adulterated food” and a $11.2 million penalty. The penalty included an $8 million criminal fine, which was the largest ever paid in a food safety case. While the problems at the Sylvester plant were more than just insufficient contamination control, the inability to fully eliminate Salmonella Tennessee from the facility after the 2004 outbreak directly led to the problems encountered in 2006 and beyond.

Many times, bacteria are able to survive simply because of limitations of the cleaning method utilized by the sanitation program. In order for any sanitation/decontamination method to work, every organism must be contacted by the chemical/agent, for the proper amount of time and at the correct concentration by an agent effective against that organism. Achieving those requirements is difficult for some sanitation methods and impossible for others. Common sanitation methods include steam, isopropyl alcohol, quaternary ammonium compounds, peracetic acids, bleach and ozone, all of which have a limited ability to reach all surfaces within a space, and some are incapable of killing all microorganisms.

Liquids, fogs and mists all have difficulty achieving an even distribution throughout the area, with surfaces closer or easier to reach (i.e., the top or front of an item), receiving a higher dosage than surfaces further away or in hard-to-reach areas. Such hard-to-reach areas for common sanitation methods include the bottom, back or insides of items and equipment that don’t receive a “direct hit” from the decontaminant. Liquids, fogs and mists land on and stick to surfaces, which makes it harder for them to reach locations outside the line of sight from where they are injected or sprayed. Hard-to-reach areas also include ceilings, the tops of overhead piping lines, HVAC vents, cooling coils and other surfaces that are located at greater heights than the liquids, fogs and mists can reach due to gravitational effects on the heavy liquid and vapor molecules.

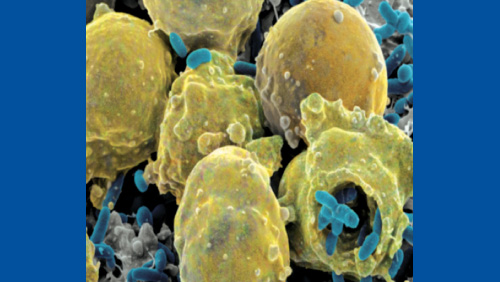

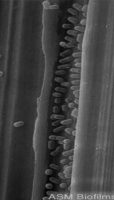

Another common but extreme hard-to-reach area includes any cracks and crevices within a facility. Although crevices are to be avoided within production facilities (and should be repaired if found), it is impossible to guarantee that there are no cracks or crevices within the production area at all. Liquid disinfectants and sterilant methods deal with surface tension, which prevents them from reaching deep into cracks. Vapor, mist and fog particles tend to clump together due to strong hydrogen bonding between molecules, which often leave them too large to fit into crevices. Figure 1 shows bacteria found in a scratch in a stainless steel surface after it had been wiped down with a liquid sterilant. The liquid sterilant was unable to reach into the scratch and kill/remove the bacteria. The bacteria were protected by the crevice created by the scratch, giving them a safe harbor location where they could replicate and potentially exit in the future to contaminate product itself.

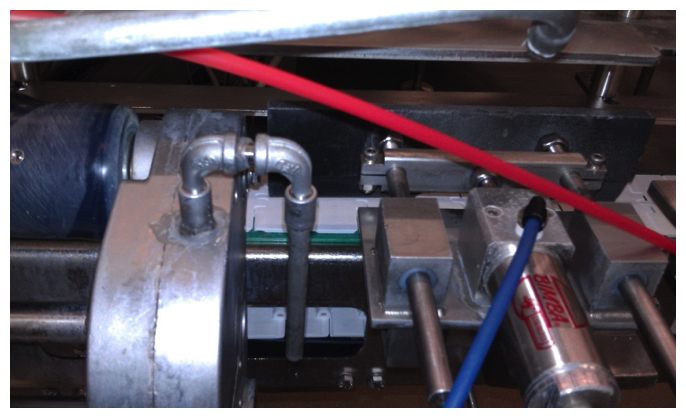

Processing equipment and machinery in general contain many hard-to-reach areas, which challenge the routine cleaning process. In sanitation, “hard to reach” is synonymous with “hard to clean”. Figure 2 shows processing equipment from an ice cream manufacturing facility. Processing equipment cannot be manufactured to eliminate all hard-to-clean areas. As such, even with all the sanitary design considerations possible, it is impossible to have equipment that does not contain any hard-to-clean areas. While sanitary design is essential, additional steps must be taken to further reduce the possibility of contamination and the risk that comes along with it. This means that in order to improve one’s contamination control and risk management programs, improvements must also be made to the sanitation program and the methods of cleaning and decontamination used.

Chlorine Dioxide Gas

Food safety attorney Shawn K. Stevens recently wrote that “given the risk created by the FDA’s war on pathogens, food companies should invest in technologies to better control pathogens in the food processing environments.”1 One method that is able to overcome the inherent difficulties of reaching all pathogens within a food processing environment is chlorine dioxide gas (ClO2 gas). ClO2 gas is a proven sterilant capable of eliminating all viruses, bacteria, fungi, and spores. As a true gas, ClO2 gas follows the natural gas laws, which state that it fills the space it is contained within evenly and completely. The chlorine dioxide molecule is smaller than the smallest viruses and bacteria. Combined, this means that ClO2 gas is able to contact all surfaces within a space and penetrate into cracks further than pathogens can, allowing for the complete decontamination of all microorganisms with the space. It also does not leave residues, making it safe for the treatment of food contact surfaces. It has been used to decontaminate a growing number of food facilities for both contamination response and contamination prevention in order to ensure sterility after renovations, equipment installations and routine plant shutdowns.

Conclusion

“If food companies do not take extraordinary measures to identify Lm in their facilities, perform a comprehensive investigation to find the root cause or source, and then destroy and eliminate it completely, the pathogen will likely persist and, over time, intermittently contaminate their finished products,” wrote Stevens.1 Environmental monitoring and sampling programs have been improved in terms of both technology and technique to better achieve the goal of identifying Lm or other pathogens within a food production environment. The FDA will be aggressive in its environmental monitoring and sampling under the food safety guidelines required by FSMA. Food production facilities will be closely monitored and tracked using PulseNet, with contaminated product being traced back to their source. Recurring contamination by a persistent pathogen will be viewed more severely. While there are many reasons that pathogens can persist within a food manufacturing environment, insufficient cleaning and decontamination is the most common. Traditional cleaning methods are incapable of reaching all surfaces and crevices within a space. In order to eliminate the risk of pathogens re-contaminating a facility, the pathogens need to be fully eliminated from their source and harbor locations. ClO2 gas is a method capable of delivering guaranteed elimination of all pathogens to maintain a pathogen-free environment. With the new era of food safety upon us, ensuring a clean food production environment is more important than ever, and ClO2 gas is uniquely situated to help reduce the risk and liability provided by both the government and the public.

In the summer of 2015, multiple ice cream manufacturers were affected by Listeria monocytogenes contamination. Part two of this article will detail one such company that utilized ClO2 gas to eliminate Listeria from its facility.

Reference

- Stevens, S.K. (June 3, 2016). “Find Contamination, Reduce Pathogens, and Decrease Criminal Liability”. Retrieved from https://foodsafetytech.com/column/find-contamination-reduce-pathogens-decrease-criminal-liability/