Preventing Outbreaks a Matter of How, Not When

When it comes to preventing foodborne illness, staying ahead of the game can be an elusive task. In light of the recent outbreaks affecting Chipotle (norovirus, Salmonella, E. coli) and Dole’s packaged salad (Listeria), having the ability to identify potentially deadly outbreaks before they begin (every time) would certainly be the holy grail of food safety.

One year ago IBM Research and Mars, Inc. embarked on a partnership with that very goal in mind. They established the Consortium for Sequencing the Food Supply Chain, which they’ve touted as “the largest-ever metagenomics study…sequencing the DNA and RNA of major food ingredients in various environments, at all stages in the supply chain, to unlock food safety insights hidden in big data”. The idea is to sequence metagenomics on different parts of the food supply chain and build reference databases as to what is a healthy/unhealthy microbiome, what bacteria lives there on a regular basis, and how are they interacting. From there, the information would be used to identify potential hazards, according to Jeff Welser, vice president and lab director at IBM Research–Almaden.

“Obviously a major concern is to always make sure there’s a safe food supply chain. That becomes increasingly difficult as our food supply chain becomes more global and distributed [in such a way] that no individual company owns a portion of it,” says Welser. “That’s really the reason for attacking the metagenomics problem. Right now we test for E. coli, Listeria, or all the known pathogens. But if there’s something that’s unknown and has never been there before, if you’re not testing for it, you’re not going to find it. Testing for the unknown is an impossible task.” With the recent addition of the diagnostics company Bio-Rad to the collaborative effort, the consortium is preparing to publish information about its progress over the past year. In an interview with Food Safety Tech, Welser discusses the consortium’s efforts since it was established and how it is starting to see evidence that using microbiomes could provide insights on food safety issues in advance.

Food Safety Tech: What progress has the Consortium made over the past year?

Jeff Welser: For the first project with Mars, we decided to focus around pet food. Although they might be known for their chocolates, at least half of Mars’ revenue comes from the pet care industry. It’s a good area to start because it uses the same food ingredients as human food, but it’s processed very differently. There’s a large conglomeration of parts in pet food that might not be part of human food, but the tests for doing the work is directly applicable to human food. We started at a factory of theirs and sampled the raw ingredients coming in. Over the past year, we’ve been establishing whether we can measure a stable microbiome (if we measure day to day, the same ingredient and the same supplier) and [be able to identify] when something has changed.

At a high level, we believe the thesis is playing out. We’re going to publish work that is much more rigorous than that statement. We see good evidence that the overall thesis of monitoring the microbiome appears to be viable, at least for raw food ingredients. We would like to make it more quantitative, figure out how you would actually use this on a regular basis, and think about other places we could test, such as other parts of the factory or machines.

FST: What are the steps to sequencing a microbiome?

Welser: A sample of food is taken into a lab where a process breaks down the cell walls to release the DNA and RNA into a slurry. A next-generation sequencing machine identifies every snippet of DNA and RNA it can from that sample, resulting in huge amounts of data. That data is transferred to IBM and other partners for analysis of the presence of organisms. It’s not a straightforward calculation, because different organisms often share genes or have similar snippets of genes. Also, because you’ve broken everything up, you don’t have a full gene necessarily; you might have a snippet of a gene. You want to look at different types of genes and different areas to identify bad organisms, etc. When looking at DNA and RNA, you want to try to determine if an organism is currently active.

The process is all about the analysis of the data sequence. That’s where we think it has a huge amount of possibility, but it will take more time to understand it. Once you have the data, you can combine it in different ways to figure out what it means.

FST: Discuss the significance of the sequencing project in the context of recent foodborne illness outbreaks. How could the information gleaned help prevent future outbreaks?

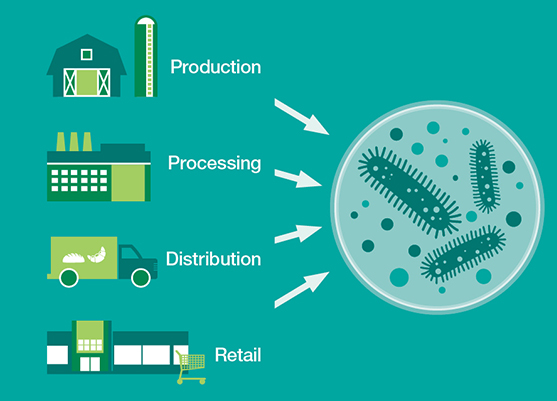

Welser: In general, this is exactly what we’re hoping to achieve. Since you test the microbiome at any point in the supply chain, the hope is that it gives you much better headlights to a potential contamination issue wherever it occurs. Currently raw food ingredients come into a factory before they’re processed. If you see the problem with the microbiome right there, you can stop it before it gets into the machinery. Of course, you don’t know whether it came in the shipment, from the farm itself, etc. But if you’re testing in those places, hopefully you’ll figure that out as early as possible. On the other end, when a company processes food and it’s shipped to the store, it goes onto the [store] shelves. It’s not like anyone is testing on a regular basis, but in theory you could do testing to see if the ingredient is showing a different microbiome than what is normally seen.

The real challenge in the retail space is that today you can test anything sitting on the shelves for E. coli, Listeria, etc.— the [pathogens] we know about. It’s not regularly done when [product] is sitting on the shelves, because it’s not clear how effectively you can do it. It still doesn’t get over the challenge of how best to approach testing—how often it needs to be done, what’s the methodology, etc. These are all still challenges ahead. In theory, this can be used anywhere, and the advantage is that it would tell you if anything has changed [versus] testing for [the presence of] one thing.

FST: How will Bio-Rad contribute to this partnership?

Welser: We’re excited about Bio-Rad joining, because right now we’re taking samples and doing next-generation sequencing to identify the microbiome. It’s much less expensive than it used to be, but it’s still a fairly expensive test. We don’t envision that everyone will be doing this every day in their factory. However, we want to build up our understanding to determine what kinds of tests you would conduct on a regular basis without doing the full next-gen sequencing. Whenever we do sequencing, we want to make sure we’re doing the other necessary battery of tests for that food ingredient. Bio-Rad has expertise in all these areas, and they’re looking at other ways to advance their testing technology into the genomic space. That is the goal: To come up with a scientific understanding that allows us to have tests, analysis and algorithms, etc. that would allow the food industry to monitor on a regular basis.

FST: What is the next step for the sequencing project?

Welser: Once we finish the current work, we want to expand to a larger list of ingredients and do testing on the factory floor. In parallel, this coming year we expect to start addressing the question of how this would be used in a factory. Assuming I’m going to start by mapping the food ingredients that come in, what’s the right protocol for testing? What would be a prototype of how one could use a factory sequencing on a regular basis? That’s where Bio-Rad comes in as well, because the answer is not just scientific, it’s economic. How can this be done in a way that is economically feasible? To what extent does this complement existing testing versus whether it can replace certain [types of] testing over time? What else does this teach you in terms of the knowledge that comes out from it? How do you implement both the software and the testing protocols?

One of the most exciting things to Mars is seeing how we could implement this in a factory. Today, they and every food producer, do huge amounts of testing daily and spend millions of dollars doing it. Fortunately, 99.999% they find nothing. That means they’ve spent all that money and haven’t learned anything. The hope is that once you do [this sequencing], you’ll find what the microbiome looks like on that day and build up a huge database of how the microbiome shifts over time. We’re not talking about dangerous shifts or indicating that anything is wrong. But we know from other research on microbiomes that it changes daily and seasonally.

What can we learn from this to help us make further improvements? Maybe we will find that certain microbiomes preserve food longer, particularly in the fresh produce area. Are there certain microbiomes that would keep a tomato fresher on the shelves longer? Are there microbiomes that would be healthier for someone to eat? The hope is that running this [sequencing] everyday in the factory will give you information in the database that you can build on and gain analytics. Thus the money is serving two purposes: To keep food safe and to increase our knowledge about how to make food more healthful and nutritional.