We developed a system that tracks food fraud records using four categories: Incidents, inference records, surveillance records and method records. Food fraud incidents are documented occurrences of fraud that include contextual information about location, perpetrators, timeframe, geographic location and other characteristics. In many ways, incidents are the gold standard of food fraud records. However, there have been unsubstantiated reports of food fraud that were subsequently discredited (such as the “plastic rice” scandal of a few years ago). For this reason, for every incident we capture, we assign a “weight of evidence” classification to provide our assessment of the strength of the evidence. For example, incidents reported directly by regulatory agencies with supporting documentation will generally be assigned a “high” weight of evidence classification.

We also work diligently to avoid “double counting” food fraud incidents, although at times this can be challenging. Incidents may be reported in multiple media outlets and, at times, the reports may not include enough information to determine if it is a new report or related to an issue already reported. We cross-reference the dates and locations of reports, along with information about the ingredients and adulterants, to help ensure that isolated food fraud cases are reported as one incident.

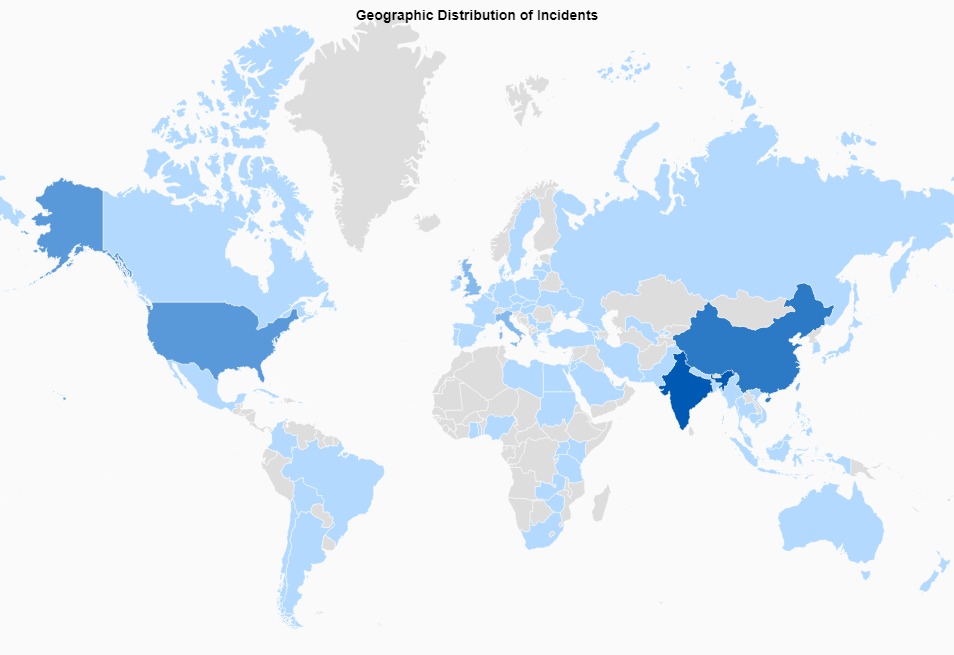

Incidents we have captured in the past two months include $14 million of counterfeit wine discovered in China, which was reportedly based on a tip off. The Carabinieri and ICQRF in Italy discovered wines with added flavorings and other additives. The Guardia di Finanza in Italy also seized adulterated extra virgin olive oil. Counterfeit liquor was discovered in Russia and bootleg liquor containing methanol caused deaths in Malaysia.

Expired (possibly rotting) eggs intended to be powdered and used in food production were discarded by regulatory authorities in India. A customer in China reported that expired carrots were being re-labeled with new dates. Adulterated milk was discovered in Pakistan. In Kenya, reports surfaced of sodium metabisulfite being used on meat to enhance its appearance. Finally, in the United States, two companies were indicted for importing giant squid and selling it domestically as octopus (which usually has a higher retail price) over a period of three years. A review of these reports illustrates how challenging it can be to collect and standardize food fraud information, especially when it is reported in media sources.