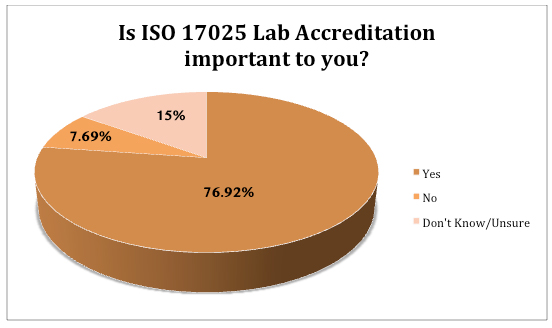

With the increasing globalization of the food industry, ensuring that products reaching consumers are safe has never been more important. Local, state and federal regulatory agencies are increasing their emphasis on the need for food and beverage laboratories to be accredited to ISO/IEC 17025 compliance. This complicated process can be simplified and streamlined through the adoption of LIMS, making accreditation an achievable goal for all food and beverage laboratories.

With a global marketplace and complex supply chain, the food industry continues to face increasing risks for both unintentional and intentional food contamination or adulteration.1 To mitigate the risk of contaminated products reaching consumers, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), using a consensus-based approval process, developed the first global laboratory standard in 1999 (ISO/IEC 17025:1999). Since publication, the standard has been updated twice, once in 2005 and most recently in 2017, and provides general requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories.2

In the recent revision, four key updates were identified:

- A revision to the scope to include testing, calibration and sampling associated with subsequent calibration and testing performed by a laboratory.3

- An emphasis on the results of a process instead of focusing on prescriptive procedures and policies.4

- The introduction of the concept of a risk-based approach used in production quality management systems.2

- A stronger focus on information technologies/management systems, specifically Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS).4

As modern-day laboratories reduce their reliance on hard copy documents and transition to electronic records, additional emphasis and guidance for ISO 17025 accreditation in food testing labs using LIMS was greatly needed. Food testing laboratories have increased reliance on LIMS to successfully meet the requirements of accreditation. Food and beverage LIMS has evolved to increase a laboratory’s ability to meet all aspects of ISO 17025.

Traceability

Chain of Custody

A key element for ISO 17025 accredited laboratories is the traceability of samples from accession to disposal.5 Sometimes referred to as chain of custody, properly documented traceability allows a laboratory to tell the story of each sample from the time it arrives until the time it is disposed of.

LIMS software allows for seamless tracking of samples by employing unique sample accession numbers through barcoding processes. At each step of sample analysis, a laboratory technician updates data in a LIMS by scanning the sample barcode, establishing time and date signatures for the analysis. During an ISO 17025 audit, this information can be quickly obtained for review by the auditor.

Procurement and Laboratory Supplies

ISO 17025 requires the traceability of all supplies or inventory items from purchase to usage.6 This includes using approved vendors, documentation of receipt, traceability of supply usage to an associated sample, and for certain products, preparation of supply to working conditions within the laboratory. Supply traceability impacts multiple departments and coordinating this process can be overwhelming. A LIMS for food testing labs helps manage laboratory inventory, track usage of inventory items, and automatically alerts laboratory managers to restock inventory once the quantity falls below a threshold level.

A food LIMS can ensure that materials are ordered from approved vendors only, flagging items purchased outside this group. As supplies are inventoried into LIMS, the barcoding process can ensure accurate storage. A LIMS can track the supply through its usage and associate it with specific analytical tests for which inventory items are utilized. As products begin to expire, a LIMS can notify technicians to discard the obsolete products.

One unique advantage of a fully integrated LIMS software is the preparation and traceability of working laboratory standards. A software solution for food labs can assist a technician in preparing standards by determining the concentration of solvents needed based on the input weight from a balance. Once prepared, LIMS prints out a label with barcodes and begins the supply traceability process as previously discussed.

Quality Assurance of Test and Calibration Data

This section of ISO 17025 pertains to the validity of a laboratory’s quality system including demonstrating that appropriate tests were performed, testing was conducted on properly maintained and calibrated equipment by qualified personnel, and with appropriate quality control checks.

Laboratory Personnel Competency

Laboratory personnel are assigned to a specific scope of work based upon qualifications (education, training and experience) and with clearly defined duties.7 This process adds another layer to the validity of data generated during analysis by ensuring only appropriate personnel are performing the testing. However, training within a laboratory can be one of the most difficult components of the accreditation process to capture due to the rapid nature in which laboratories operate.

With a food LIMS, management can ensure employees meet requirements (qualifications, competency) as specified in job descriptions, have up-to-date training records (both onboarding and ongoing), and verify that only qualified, trained individuals are performing certain tests.

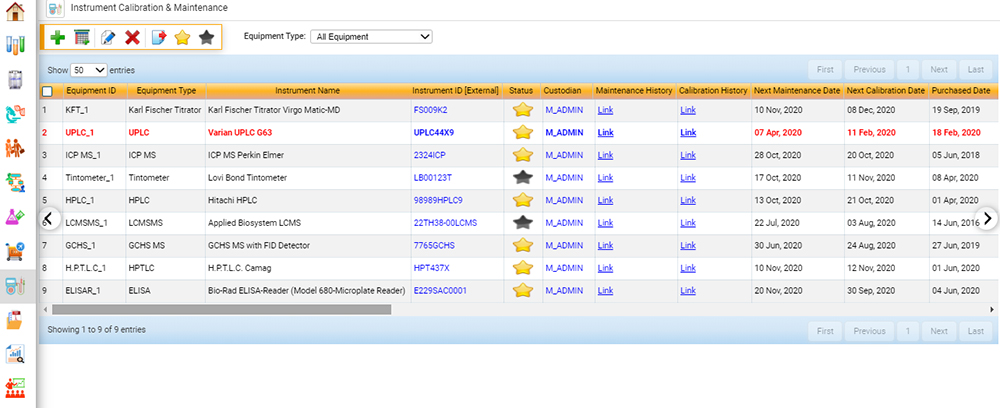

Calibration and Maintenance of Equipment

Within the scope of ISO 17025, food testing laboratories must ensure that data obtained from analytical instruments is reliable and valid.5 Facilities must maintain that instruments are in correct operating condition and that calibration data (whether performed daily, weekly, or monthly) is valid. As with laboratory personnel requirements, this element to the standard adds an additional layer of credibility that sample data is precise, accurate, and valid.

A fully integrated software solution for food labs sends a notification when instrument calibration is out of specification or expired and can keep track of both routine internal and external maintenance on instruments, ensuring that instruments are calibrated and maintained regularly. Auditors often ask for instrument maintenance and calibration records upon the initiation of an audit, and LIMS can swiftly provide this information with minimal effort.

Measurement of Uncertainty (UM)

Accredited food testing laboratories must measure and report the uncertainty associated with each test result.8 This is accomplished by using certified reference materials (CRM), or known spiked blanks. UM data is trended using control charts, which can be prepared using labor-intensive manual input or performed automatically using LIMS software. A fully integrated food LIMS can populate control data from the instrument into the control chart and determine if sample data analyzed in that batch can be approved for release.

Valid Test Methods and Results

Accurate test and calibration results can only be obtained with methods that are validated for the intended use.5 Accredited food laboratories should use test methods that are current and contain embedded quality control standards.

A LIMS for food testing labs can ensure correct method selection by technicians by comparing data from the sample accession input with the test method selected for analysis. Specific product identifiers can indicate if methods have been validated. As testing is performed, a LIMS can track time signatures to ensure protocols are properly performed. At the end of the analysis, results of the quality control samples are linked to the test samples to ensure only valid results are available for clients. Instilling checks at each step of the process allows a LIMS to auto-generate Certificates of Analysis (CoA) knowing that the testing was performed accurately.

Data Integrity

The foundation of a laboratory’s reputation is based on its ability to provide reliable and accurate data. ISO 17025:2017 includes specific references to data protection and integrity.10 Laboratories often claim within their quality manuals that they ensure the integrity of their data but provide limited details on how it is accomplished making this a high priority review for auditors. Data integrity is easily captured in laboratories that have fully integrated their instrumentation into LIMS software. Through the integration process, data is automatically populated from analytical instruments into a LIMS. This eliminates unintentional transcription errors or potential intentional data manipulation. A LIMS for food testing labs restricts access to changing or modifying data, allowing only those with high-level access this ability. To control data manipulation even further, changes to data auto-populated in LIMS by integrated instrumentation are tracked with date, time, and user signatures. This allows an auditor to review any changes made to data within LIMS and determine if appropriate documentation was included on why the change was made.

Sampling

ISO 17025:2017 requires all food testing laboratories to have a documented sampling plan for the preparation of test portions prior to analysis. Within the plan, the laboratory must determine if factors are addressed that will ensure the validity of the testing, ensure that the sampling plan is available to the laboratory (or the site where sampling is performed), and identify any preparation or pre-treatment of samples prior to analysis. This can include storage, homogenization (grinding/blending) or chemical treatments.9

As sample information is entered into LIMS, the software can specify the correct sampling method to be performed, indicate appropriate sample storage conditions, restrict the testing to approved personnel and provide electronic signatures for each step.

Monitoring and Maintenance of the Quality System

Organization within a laboratory’s quality system is a key indicator to assessors during the audit process that the facility is prepared to handle the rigors that come with accreditation.10 Assessors are keenly aware of the benefits that a food LIMS provides to operators as a single, well-organized source for quality and technical documents.

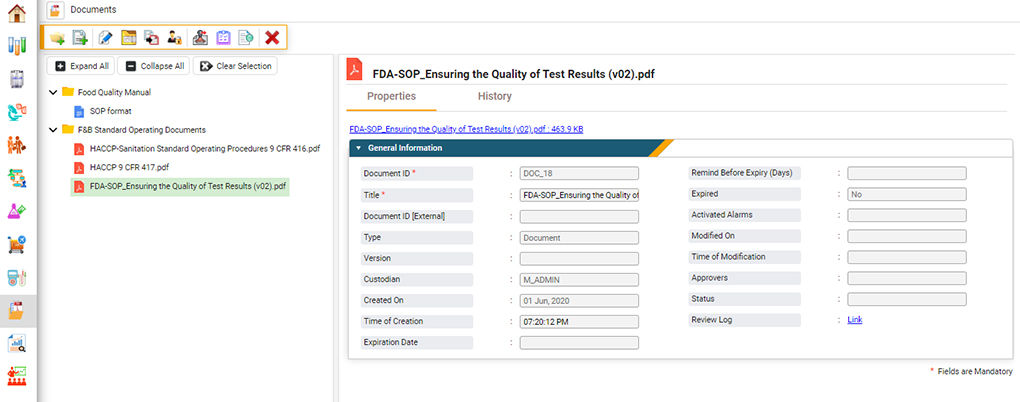

Document Control

An ISO 17025 accredited laboratory must demonstrate document control throughout its facility.6 Only approved documents are available for use in the testing facility, and the access to these documents is restricted through quality control. This reduces the risk of document access or modification by unauthorized personnel.

LIMS software efficiently facilitates this process in several ways. A food LIMS can restrict access to controlled documents (both electronic and paper) and require electronic signatures each time approved personnel access, modify or print them. This digital signature provides a chain of custody to the document, ensuring that only approved controlled documents are used during analyses and that these documents are not modified.

Corrective Actions/Non-Conforming Work

A fundamental requirement for quality systems is the documentation of non-conforming work, and subsequent corrective action plans established to reduce their future occurrence.5

A software solution for food labs can automatically maintain electronic records of deviations in testing, flagging them for review by quality departments or management. After a corrective action plan has been established, LIMS software can monitor the effectiveness of the corrective action by identifying similar non-conforming work items.

Conclusion

Food and beverage testing laboratories are increasingly becoming accredited to ISO 17025. With recent changes to ISO 17025, the importance of LIMS for the food and beverage industry has only amplified. A software solution for food labs can integrate all parts of the accreditation process from personnel qualification, equipment calibration and maintenance, to testing and methodologies.11 Fully automated LIMS increases laboratory efficiency, productivity, and is an indispensable tool for achieving and maintaining ISO 17025 accreditation.

References

- Spink, J. (2014). Safety of Food and Beverages: Risks of Food Adulteration. Encyclopedia of Food Safety (413-416). Academic Press.

- International Organization for Standardization (October 2017). ISO/IEC 17025 General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories. Retrieved from: https://www.iso.org/files/live/sites/isoorg/files/store/en/PUB100424.pdf

- 17025 Store (2018). Transitioning from ISO 17025:2005 to ISO/IEC 17024:2017. Standards Store.

- Perry Johnson Laboratory Accreditation (2019). An Overview of Changes Between 17025:2005 and 17025:2017. ISO/IEC 17025:2017 Transition. https://www.pjlabs.com/downloads/17025-Transition-Book.pdf

- Analytical Laboratory Accreditation Criteria Committee. (2018). AOAC INTERNATIONAL Guidelines for Laboratories Performing Microbiological and Chemical Analyses of Food, Dietary Supplements, and Pharmaceuticals, An Aid to Interpretation of ISO/IEC 17025. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Cokakli, M. (September 4, 2020). Transitioning to ISO/IEC 17025:2017. New Food Magazine.

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017. General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories.

- Bell, S. (1999). A Beginner’s Guide to Uncertainty of Measurement. Measurement Good Practice Guide. 11 (2).

- 17025Store (2018). Clause 7: Process requirements. Standards Store.

- Dell’Aringa, J. (March 27, 2017). Best Practices for ISO 17025 Accreditation: Preparing for a Food Laboratory Audit (Part I). Food Safety Tech.

- Apte, A. (2020). Preparing for an ISO 17025 Audit: What to Expect from a LIMS?