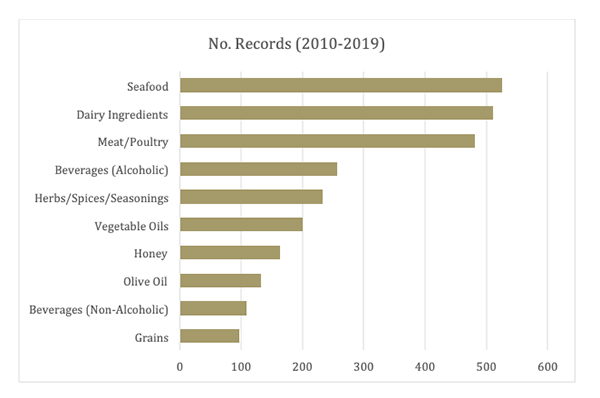

I recently attended two webinars that highlighted distinct perspectives on two challenging aspects of food fraud prevention. First, Chris Elliott from Queen’s University Belfast discussed the current situation with meat fraud. He cited his “top three” fraud-prone foods as meat, olive oil and honey. While we cannot determine the true scope of food fraud globally, looking at the data we have collected from the past 10 years, meat is also in our “top three.”

Meat is prone to fraud in many ways, including misrepresenting the animal species, fraudulent labeling of production practices (organic, kosher, halal, etc.), the use of unapproved additives, the addition of non-meat-based protein ingredients, and misrepresentation of geographic origin (among others).

Elliott discussed some of the reasons that meat is prone to fraud, which included the fact that the industry is highly competitive, relies on low profit margins, and the supply network can be complex. Discussing specifically the horsemeat scandal in Europe a few years ago, he cited the “mess of subcontracts” involved in the adulterated meat, which were based primarily on price. He finished his presentation by noting that certain aspects of meat authentication are still challenging from an analytical perspective, such as ensuring country of origin and verifying the claims about animal feed consumption.

The final in a series of food fraud webinars sponsored by the IAFP Food Fraud Professional Development Group (PDG) focused on another aspect of food fraud: E-commerce. One of the big challenges with food fraud is the intentional nature of the crime, which can make anticipation of adulterants and fraud methods difficult.

GFSI has stated “any plans and activities to mitigate, prevent or even understand the risks associated with food fraud should consider an entire company’s activities, including some that may not be within the traditional food safety or even HACCP scope, applying methods closer to criminal investigation.” This is particularly true for fraud involving intellectual property (IP) infringement, which adds another layer of complexity to detection and prevention strategies. We have more than 200 records documenting fraud involving “counterfeit” products. Counterfeit products are a problem both because of the IP infringement and because, often, the actual contents of the product cannot be verified. Many of the records we have documented involve counterfeit vodka, whiskey, and wine, as well as non-alcoholic soft drinks.

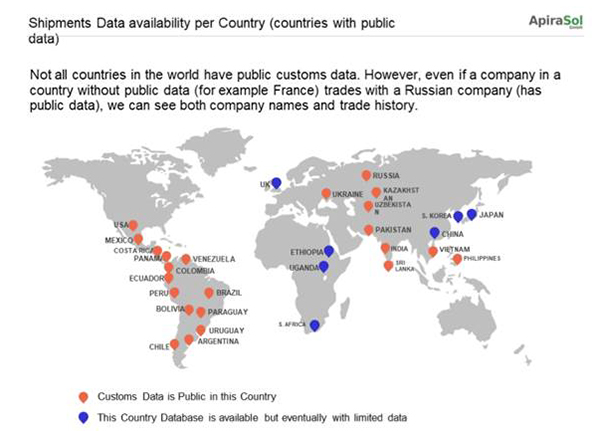

As part of the IAFP webinar, Axel Hein from ApiraSol discussed their work using global customs data to detect counterfeit products, so-called “fantasy trademarks,” and geographical indication infringements.

Many countries provide public access to customs data which, when aggregated and combined with other sources (such as Alibaba transactions), allows mapping of supply chains and detection of unusual patterns that may indicate fraud. In school, I spent many months digging through U.S. customs data trying to uncover patterns that might indicate fraud, so I was very interested to see this being done on a larger scale.

Although each webinar was distinct in its focus, each highlighted the importance of supply chain control and monitoring in mitigating food fraud risk. To paraphrase a point made by Elliott, each arrow in a supply network is a potential vulnerability. The continued globalization of the food supply requires new and innovative ways to reduce these supply chain vulnerabilities.