The COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated existing disconnects between food supply and demand. While some may be noticing these issues on a broader scale for the first time, the reality is that there have been challenges in our food supply chains for decades. A lack of accurate data and information sharing is the core of the problem and had greater impact due to the pandemic. Outdated technologies are preventing advancements and efficiencies, resulting in the paradox of mounting food insecurity and food waste.

To bridge this disconnect, the food industry needs to implement innovative AI and machine learning technologies to prevent shortages, overages and waste as COVID-19 subsides. Solutions that enable data sharing and collaboration are essential to build more resilient food supply chains for the future.

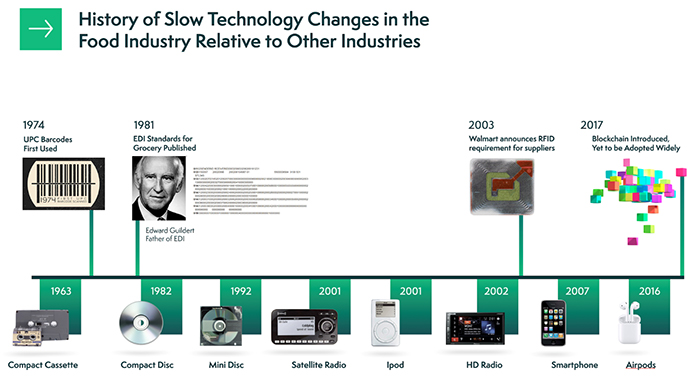

Data-sharing technologies that can help alleviate these problems have been under development for decades, but food supply chains have been slow to innovate compared to other industries. By reviewing the top four data-sharing technologies used in food industry and the year they were introduced to food supply chains, it’s evident that the pace of technology innovation and adoption needs to accelerate to advance the industry.

A History of Technology Adoption in the Food Industry

The Barcode – 19741

We’re all familiar with the barcode—that assemblage of lines translated into numbers and letters conveying information about a product. When a cashier scans a barcode, the correct price pops up on the POS, and the sale data is recorded for inventory management. Barcodes are inexpensive and easy to implement. However, they only provide basic information, such as a product’s name, type, and price. Also, while you can glean information from a barcode, you can’t change it or add information to it. In addition, barcodes only group products by category—as opposed to radio-frequency identification (RFID), which provides a different code for every single item.

EDI First Multi-Industry Standards – 19812

Electronic data interchange (EDI) is just what it sounds like—the concept of sharing information electronically instead of on paper. Since EDI standardizes documents and the way they’re transferred, communication between business partners along the supply chain is easier, more efficient, and human error is reduced. To share information via EDI, however, software is required. This software can be challenging for businesses to implement and requires IT expertise to handle updates and maintenance.

RFID in the Food Supply Chain – 20033

RFID and RFID tags are encoded with information that can be transmitted to a reader device via radio waves, allowing businesses to identify and track products and assets. The reader device translates the radio waves into usable data, which then lands in a database for tracking and analysis.

RFID tags hold a lot more data than barcodes—and data is accessible in remote locations and easily shared along the supply chain to boost transparency and trust. Unlike barcode scanners, which need a direct line of sight to a code, RFID readers can read multiple tags at once from any direction. Businesses can use RFID to track products from producer to supplier to retailer in real time.

In 2003, Walmart rolled out a pilot program requiring 100 of its suppliers to use RFID technology by 2005.3 However, the retail giant wasn’t able to scale up the program. While prices have dropped from 35–40 cents during Walmart’s pilot to just 5 cents each as of 2018, RFID tags are still more expensive than barcodes.4 They can also be harder to implement and configure. Since active tags have such a long reach, businesses also need to ensure that scammers can’t intercept sensitive data.

Blockchain – 20175

A blockchain is a digital ledger of blocks (records) used to record data across multiple transactions. Changes are recorded in real-time, making the history unfalsifiable and transparent. Along the food supply chain, users can tag food, materials, compliance certificates and more with a set of information that’s recorded on the blockchain. Partners can easily follow the item through the physical supply chain, and new information is recorded in real-time.

Blockchain is more secure and transparent, less vulnerable to fraud, and more scalable than technologies like RFID. When paired with embedded sensors and RFID tags, the tech offers easier record-keeping and better provenance tracking, so it can address and help solve traceability problems. Blockchain boosts trust by reducing food falsification and decreasing delays in the supply chain.6

On the negative side, the cost of transaction processing with blockchain is high. Not to mention, the technology is confusing to many, which hinders adoption. Finally, while more transparency is good news, there’s such a thing as too much transparency; there needs to be a balance, so competitors don’t have too much access to sensitive data.

Cloud-Based Demand Forecasting – 2019 to present7

Cloud-based demand forecasting uses machine learning and AI to predict demand for various products at different points in the food supply chain. This technology leverages other technologies on this list to enhance communication across supply chain partners and improve the accuracy of demand forecasting, resulting in less waste and more profit for the food industry. It enables huge volumes of data to be used to predict demand, including past buying patterns, market changes, weather, events and holidays, social media input and more to create a more accurate picture of demand.

The alternative to cloud-based demand forecasting that is still in use today involves Excel or manual spreadsheets and lots of number crunching, which are time-intensive and prone to human error. This manual approach is not a sustainable process, but AI, machine learning and automation can step in to resolve these issues.

Obtaining real-time insights from a centralized, accurate and accessible data source enables food suppliers, brokers, distributors, brands and retailers to share information and be nimble, improving their ability to adjust supply in response to factors influencing demand.8 This, in turn, reduces cost, time and food waste, since brands can accurately predict how much to produce down to the individual SKU level, where to send it and even what factors might impact it along the way.

Speeding Up Adoption

As illustrated in Figure 1, the pace of technology change in the food industry has been slow compared to other industries, such as music and telecommunications. But we now have the tools, the data and the brainpower to create more resilient food supply chains.

Given the inherent connectivity of partners in the food supply chain, we now need to work together to connect information systems in ways that give us the insights needed to deliver exactly the rights foods to the right places, at the right time. This will not only improve consumer satisfaction but will also protect revenue and margins up and down food supply chains and reduce global waste.

References

- Weightman, G. (2015). The History of the Bar Code. Smithsonian Magazine.

- Locken, S. (2012). History of EDI Technology. EDI Alliance.

- Markoff, R, Seifert, R. (2019). RFID: Yesterday’s blockchain. International Institute for Management Development.

- Wollenhaupt, G. (2018). What’s next for RFID? Supply Chain Dive.

- Tran, S. (2019). IBM Food Trust: Cutting Through the Complexity of the World’s Food Supply with Blockchain. Blockchain News.

- Galvez, J, Mejuto, J.C., Simal-Gandara, J. (2018). Future Challenge on the use of blockchain for food traceability analysis. Science Direct.

- (2019). Crisp launches with $14.2 million to cut food waste using big data. Venture Beat.

- Dixie, G. (2005). The Impact of Supply and Demand. Marketing Extension Guide.