The seafood supply chain handles 158 million metric tons of product every year, 50% of which comes from wild sources. Operating in every ocean on the planet, the industry is struggling to figure out how to overcome the numerous obstacles to traceability, which include unregulated fishing, food fraud and unsustainable fishing practices. With these and other problems continuously plaguing the supply chain, distributors and importers cannot consistently guarantee the validity, source or safety of their products. Furthermore, there are limits to what a buyer or retailer can demand of the supply chain. Niche solutions abound, but a panacea has yet to be found.

In this complex environment, there are increasing calls for better supply chain management and “catch to plate” provenance. One problem, however: The industry as a whole still regards traceability as a cost rather than an investment. There are signs this attitude is changing, however, perhaps due to pressure from consumers, governments and watchdog-type organizations to “clean up” the business and address the mounting evidence that unsustainable fishing practices cause significant environmental problems. Today, we’ve arrived at a moment when industry leaders are being proactive about transparency and technologies such as mobile applications and environmental monitoring software can genuinely help reform the seafood supply chain.

A Global Movement for Seafood Traceability

There are several prominent examples of the burgeoning worldwide commitment to traceability (and, by default, the use of new technologies) in the seafood supply chain. These include the Tuna 2020 Traceability Declaration, the Global Tuna Alliance, and the Global Dialogue on Seafood Traceability. Let’s focus on the latter to illustrate the efforts to bring traceability to the industry.

The Global Dialogue on Seafood Traceability. The GDST, or the Dialogue, is “an international, business-to-business platform established to advance a unified framework for interoperable seafood traceability practices.” It comprises industry stakeholders from different parts of the supply chain and civil society experts from around the world, working together to develop industry standards to, among other things, improve the reliability of information, make traceability less expensive, help reduce risk in the supply chain, and facilitate long-term social and environmental sustainability.

On March 16, 2020, the Dialogue launched its GDST 1.0 Standards, which will utilize the power of data to support traceability and the ability to guarantee the legal origin of seafood products. These are guidelines, not regulations; members who sign a pledge commit themselves to bringing these standards to their supply chains.

GDST 1.0 has two objectives. First, it aims to harmonize data standards to facilitate data sharing up and down the supply chain. It calls for all nodes to create Electronic Product Code Information Services (EPCIS) events to make interoperability possible (EPCIS is a GS1 standard that allows trading partners to share information about products as they move through the supply chain.). Second, it defines the key data elements that trading partners must capture and share to ensure the supply chain is free of seafood caught through illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and to collect relevant data for resource management.

Why Transparency Is Critical

By now it’s probably clear to you that the seafood sector is in dire need of a makeover. Resource depletion, lack of trust along the supply chain, and the work of global initiatives are just a few of the factors forcing thought leaders in the industry to rethink their positions and make traceability the supply chain default.

However, despite more and more willingness among stakeholders to make improvements, the fact is that the seafood supply chain remains opaque and mind-bogglingly complex. There are abundant opportunities for products to be compromised as they change hands over and over again across the globe on their journey to consumers. The upshot is that the status quo rules and efforts to change the supply chain are under constant assault.

You may ask yourself what’s at stake if things don’t change. The answer is actually quite simple: The future of the entire seafood sector. Let’s look at a few of the most pressing problems facing the industry and how transparency can help solve them.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. IUU fishing includes fishing during off-season breeding periods, catching and selling unmanaged fish stocks, and trading in fish caught by slaves (yes, slaves). It threatens the stability of seafood ecosystems in every ocean.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, IUU fishing accounts for as much as 26 million tons of fish every year, with a value of $10–23 billion. It is “one of the greatest threats to marine ecosystems” and “takes advantage of corrupt administrations and exploits weak management regimes.” It occurs in international waters and within nations’ borders. It can have links to organized crime. It depletes resources available to legitimate operations, which can lead to the collapse of local fisheries. “IUU fishing threatens livelihoods, exacerbates poverty, and augments food insecurity.”

Transparency will help mitigate IUU fishing by giving buyers and wholesalers the ability to guarantee the source of their product and avoid seafood that has come from suspect sources. It will help shrink markets for ill-gotten fish, as downstream players will demand data that proves a product is from a legal, regulated source and has been reported to the appropriate government agencies.

International food fraud. When the supply for a perishable commodity such as seafood fluctuates, the supply chain becomes vulnerable to food fraud, the illegal practice of substituting one food for another. (For seafood, it’s most often replacing one species for another.) To keep an in-demand product flowing to customers, fishermen and restaurateurs can feel pressure to commit seafood fraud.

The problem is widespread. A 2019 report by Oceana, which works to protect and restore the Earth’s oceans, found through DNA analysis that 21% of the 449 fish it tested between March and August 2018 were mislabeled and that one-third of the establishments their researchers visited sold mislabeled seafood. Mislabeling was found at 26% of restaurants, 24% of small markets, and 12% of larger chain grocery stores. Sea bass and snapper were mislabeled the most. These results are similar to earlier Oceana reports.

Consumer health and food safety. It’s difficult to guarantee consumer health and food safety without a transparent supply chain. End-to-end traceability is critical during foodborne illness outbreaks (e.g., E. coli) and recalls, but the complex and global nature of the seafood supply chain presents a particularly daunting challenge. Species substitution (i.e., food fraud) has caused illness and death, and mishandled seafood can carry high histamine levels that pose health risks. Consumers have expectations that they are eating authentic food that is safe; the seafood industry has suffered from a lack of trust, and is starting to realize that the modern consumer landscape demands transparency.

Why Seafood Traceability Supports the Whole Supply Chain

Most seafood supply chain actors are well-intentioned companies. They regard themselves as stakeholders of a well-managed resource whose hardiness and survival are critical to their businesses and the global food supply chain. Many have implemented policies that require their buyers to verify—to the greatest extent possible—that the seafood they procure meets minimum standards for sustainability, safety and quality.

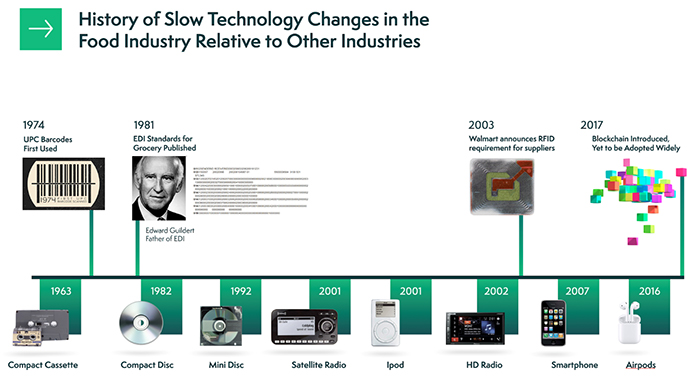

This kind of self-regulation has been an important first step, but enforcing such standards has been hampered by the lack of validated traceability systems in a digital supply chain. Of course, it costs money to implement these systems, which has been a sticking point, but industry leaders are starting to realize the value of the investment.

Suppliers. A key benefit of traceability for suppliers (i.e., processors and manufacturers) is that it allows them to really protect their business investments. Traceability achieves this because it demonstrates to consumers and trading partners that suppliers are doing things the correct way. Traceability also gives them better control over their supply chains and improves the quality of their product—other important “indicators” for consumers and trading partners.

These advantages also create opportunities for suppliers to build their brand reputations. For example, they can engage with consumers directly, using traceability data to explain that they are responsible stewards of fish populations and the environment and that their products are sustainably sourced and legitimate.

The bottom line is that suppliers that don’t modernize and digitize their supply chains probably won’t be able to stay in business. This stark realization should make them embrace traceability, as well as adopt practices that comply with the regulations that govern their operations. And once they “get with the program,” they should also be more inclined to follow initiatives and guidelines such as the GDST 1.0 Standards. This will invariably create more trust with their customers and partners.

Brands (companies) and distributors. These stakeholders also have a lot to gain from traceability. In a nutshell, they can know exactly what they’re purchasing and have peace of mind about the products’ origins, sustainability, and legitimacy. Like suppliers, they can readily comply with regulations, such as the U.S. Seafood Import Monitoring Program (SIMP), a risk-based traceability effort that requires importers to provide and report key data about 13 fish and fish products identified as vulnerable to IUU fishing and/or seafood fraud.

And, of equal importance to their own fortunes, brands and distributors can use traceability to bolster their reputations and build and solidify their relationships with customers. Being able to prove the who, what, when, where, how, and why of the products they’re selling is a powerful branding and communications tool.

The end of the supply chain: Retailers, food service groups/providers, and consumers. High-quality products with traceable provenance mean retailers and food service companies will have better supply chain control and more “ammunition” to protect their brands. As with the stakeholders above, they’ll also garner more customer loyalty. For their part, consumers will know where their seafood comes from, be assured that their food is safe, feel good about being responsible buyers, and be inclined to purchase only products they can verify.

Transparency, Technology, Trust and Collaboration

The seafood industry is at a critical point in its very long history. It’s not a new story in business: Adapt, adopt and improve or face the consequences—in this case, government penalties, sanction from environmental groups, consumer mistrust and abandonment, and decreased revenues or outright failure.

There is one twist to the story, however: What the industry does now will affect more than just its own interests. The health of all fish species, the environment, and the future of the food supply for an ever-growing population hang in the balance.

But as we’ve demonstrated, there is good news. Supply chain transparency, driven by international initiatives and new technologies, is catching on in the industry. Though companies still struggle to see transparency as an investment, not a cost, their stances seem to be softening, their attitudes changing. The writing is on the wall.

The message I want to end with is that supply chain stakeholders should know that transparency is attainable—and it needn’t be painful. Help is available from many quarters, from government and global initiatives like the GDST to consumers themselves. Working with the right solution provider is another broad avenue leading to supply chain transparency. Technology is at the point now that companies have solid options. They can integrate their current systems with new solutions. They can consider replacing outdated and expensive-to-operate systems with less complicated solutions that, in the long run, do more for less. Or they can procure an entirely new supply chain system that closes all the gaps and jumps all the hurdles to transparency.

Whatever path the industry decides follow, the time to act is now.