As much as food manufacturers take precautions to avoid all types of contaminants, there can still come a moment when you realize that your best efforts have failed. Maybe you find a broken blade or a missing wire during a sanitation break, but the product has already gone through your inline inspection machines—and nothing was detected.

This is the freak-out moment that no plant manager or quality assurance manager wants to have. Knowing that there’s possible contamination of your food product (and not knowing where that contaminant might be) creates a hailstorm of possibilities that your plant works hard to avoid. And you’re probably wondering how this could have happened in the first place.

Understanding How Contaminants Get Past Detection

To prevent physical contamination from occurring, it’s important to understand the reasons why it happens. In-house inspection systems often fail to detect contaminants for the following reasons:

- The equipment isn’t calibrated to detect contaminants to a small enough degree, or the contaminants are materials that aren’t easily detected by the in-house machinery (glass, rubber, plastic, etc.)

- The machines aren’t constantly monitored

- The speed of the production line doesn’t allow for detecting small particles

Metal detectors are the most commonly used inline inspection devices in food manufacturing, and they depend on an interference in the signal to indicate there is metal contamination in the product.

Despite the fact that technology has progressed to deliver fewer false positives, the machines can still be deceived by moisture, high salt contents and dense products that could provide interference in the signal. When that continues to occur, it’s common for manufacturers to recalibrate the machine to get fewer false positives—but that also decreases its effectiveness.

Another limitation of the metal detector is that, as the name indicates, it can only find metal. That means contaminants like plastic, glass, rubber and bone won’t be found through a metal detector, but will hopefully be discovered through some other means before the product is shipped out.

Oftentimes, contamination or suspected physical contamination is discovered when a product, such as cheese or yogurt, goes through a filtration system, or when a piece of machinery is inspected during a sanitation break.

If the machinery is found to be missing a part, such as a bolt or a rubber gasket, the manufacturer then has to backtrack to the machinery’s last inspection and determine how much, if any, of the product manufactured during that time has been contaminated.

What To Do When Contamination Occurs

Once a food manufacturer discovers that it may have a physical contamination problem, it must make a decision on how to handle the situation. Options come down to four basic choices, each of which comes with its own risks and benefits.

Option 1:

Dispose of the full production run

The one advantage of disposing of a full production run is that it entirely eliminates the possibility of the contaminated product reaching consumers.

However, this is an expensive solution, as the manufacturer has to pay for the cost of disposal in a certified landfill and absorbs the cost of packaging, labor and ingredients. It also presents the risk of lost revenue by having a product temporarily out of stock.

Option 2:

Shut down your production lines for re-inspection/re-work

Running the product through inline inspections a second time may result in finding the physical contaminant, but there’s also a risk that the contaminant won’t be found—and now the company has lost money through overtime pay and lost productivity.

If the inspection equipment was not sensitive enough to find the contaminant the first time around, it may not find it the second time, which puts the manufacturer back at square one. The advantage to this method is that the manufacturer maintains complete accountability and control over the process, although it may not yield the desired results.

Option 3:

Risk it and ship the product to retailers

There’s always a chance that a missing bolt didn’t make its way into the product. Sometimes, if a metal detector goes off and the manufacturer can’t find any contaminants upon closer examination, they will choose to ship the product and take their chances.

The advantage for them is that, on the front end, this is the least expensive option—or it could be the costliest choice of all if a consumer finds a physical contaminant in their food. In fact, the average cost of a food recall is estimated at $10 million; lawsuits may push that cost even higher and result in a business being closed for good.

Option 4:

Use third-party X-ray inspection

X-ray inspection is the most effective way to find physical contaminants. In addition to metal, X-ray systems can find glass, plastic, stone, bone, rubber/gasket material, product clumps, container defects, wood and missing components at 0.8 mm or smaller.

When a food manufacturer has a contamination issue, it can have the bracketed product inspected by a third-party X-ray inspection company and only dispose the affected food, allowing the rest of the product to be distributed. This option allows the manufacturer to maintain inventory and keep food deliveries on schedule while still eliminating the problem of contamination.

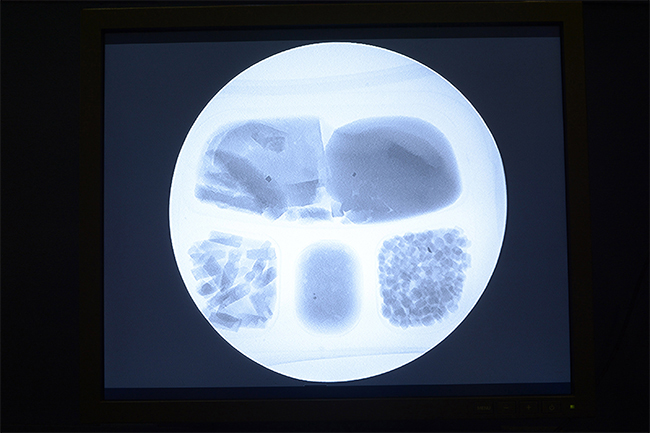

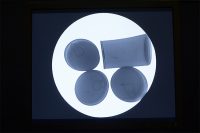

X-ray inspection can find what other forms of inspection cannot, because it’s based on the density of the product, as well as the density of the physical contaminant. When X-ray beams are directed through a food product, the rays lose some of their energy, but will lose even more energy in areas that have a physical contaminant. So when those images are interpreted on a monitor, the areas that have a physical contaminant in them will show up as a darker shade of gray.

This allows the workers monitoring machines to immediately identify any foreign particles that are in the food, regardless of the type of material.

Detection is Key to Avoiding Contamination Issues

Handling contamination properly is vital to every food manufacturing company. It affects the bottom line and the future of the company, and just one case of a physical contaminant reaching the consumer is enough to sideline food companies of any size. As X-ray technology continues to evolve, it remains an effective and efficient form of food inspection.

Educating plant managers and quality managers on what to do if inline inspection machines fail to detect contaminants should include information on how X-ray technology can be a food company’s first line of defense. While physical contaminants can’t always be avoided, they can be detected—and the future of your company may depend on it.