On the one level, it’s still too early to see full supply chain stoppages, other than growing port and customs delays. While one does not need a crystal ball to see that significant issues are already on the horizon, it takes time for both positive and negative supply impacts to wend their way through the chain.

My company, Decernis, a FoodChain ID Company, provides a complete regulatory intelligence software suite that covers more than 100,000 global regulations in 219 countries, and as such, we have a unique global perspective on how the pandemic is going to affect the supply chain.

Among the countries to watch is India, which imposed a nationwide 21-day shutdown on March 25 and thus far is the tightest lockdown in the world. In the large cities, the lack of public transportation has forced newly unemployed to walk home, often over a period of days, to their home villages. This creates a challenge for the economy because India depends on seasonal migrant and factory workers.

Unlike most countries, pharmaceutical and supplement manufacturers, as well as food processors, are entirely shut down. While farm operations and their supply chains are exempt, there is no harvest without migrant labor. Moreover, truckers transporting frozen goods often are stopped en route due to uneven permit enforcement across states. Add to this the problem of export foods stuck in containers or ports with limited market access, combined with import/export restrictions, and a crisis is at hand.

And, while the Indian government has not banned rice exports, India’s Rice Exporters Association effectively suspended exports because of dramatic labor shortages and logistical disruptions. So, while buyers exist, there is no practical way to harvest, process or ship those exports.

Combine the lack of migrant agricultural workers with the closing of restaurants and schools in many countries and economies are left with a steep drop in demand. As a result, unprocessed food including pork, eggs, milk and early-harvest fruits and vegetables are being destroyed or “tilled under.”

Countries whose leadership is turning a blind eye to the pandemic (i.e., Brazil) will ultimately see a more significant impact.

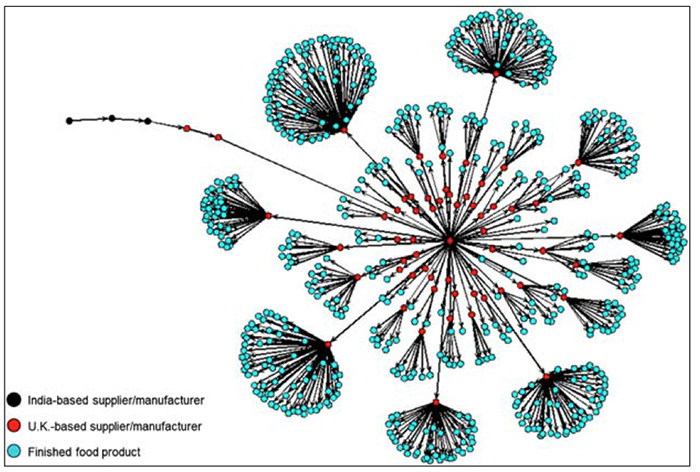

Another major player to watch is China, where the tariff crisis initially exposed supply chain vulnerabilities. Combined with the current pandemic, businesses now see that sourcing can often be a more substantial factor than price.

Prior to COVID-19, the United States, among other countries, initiated a trend toward blatant economic nationalism, which significantly accelerated this year. In an effort to protect their populations and national security, countries (i.e., Cambodia, India, Kazakhstan, Russia, Serbia and Ukraine) halted the export of vital commodities. As a result, critical supplies have been diverted to more developed countries that can outbid and pay a higher price, leading to food security risks in smaller and weaker markets.

These factors will trigger a rethinking of supply chains in the medium and long term. The cost savings realized in China, India, Vietnam and Thailand will be weighed against the threats to supply chain stability. The result may be a subtle new form of supply chain nationalism, where companies prefer more reliable local production to lower-cost, more vulnerable foreign production. The recent sourcing trend for large multinationals to partner with fewer, trusted providers could reverse once the dust settles from this pandemic.

The decrease in air cargo capacity (due to the grounding of passenger aircrafts) has also played a significant role in supply chain disruption and will lead to dramatic short-term increases in the cost of air freight.

Last, but certainly not least, will be the fallout from obvious bankruptcies. As an early indicator, 247,000 Chinese companies declared bankruptcy in the first two months of 2020, with many more closures expected.

Obvious candidates include movie theaters, airlines, cruise ships, retailers, and hotels, but any company caught carrying a large debt load is also endangered. Pharma companies and those in oil, gas and petrochemicals will also be affected by a perfect storm of oil market collapse.

On a positive note, any supplement (i.e., Vitamin B, C and D) food commodity (i.e., blueberries, oranges) and processed food products (i.e., juices, yogurts) perceived to have immunity-boosting potential will likely see a short and long-term boost in sales. Botanicals, however, may soon have significant new sourcing problems.

As they deal with consequences of this pandemic, global companies will need to strategize for building a more durable and flexible supply chain. These unprecedented times are sure to spark more innovation and technological growth to address the challenges industry is facing.