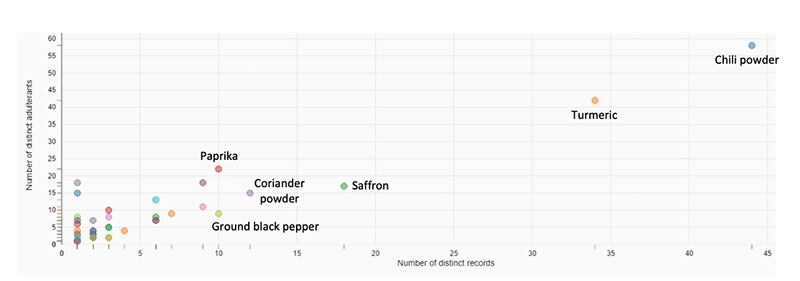

Food fraud usually does not make people sick, but we know that it can. Fraud in spices, and particularly lead adulteration of spices, appears to be getting more attention lately. Herbs/spices is one of the top five commodity groups prone to fraud, according to the data in our Food Fraud Database. Looking at the past 10 years of data for herbs/spices, chili powder, turmeric, and saffron have the highest number of fraud records and chili powder, turmeric, and paprika have the highest number of distinct adulterants associated with them (see Figure 1).*

Fraud in spices usually involves “bulking up” the spice with plant materials or other substances or the addition of unapproved coloring agents. A wide range of pigments have been detected in spices, from food-grade colors to industrial pigments, including lead-based pigments. Lead oxide was added to paprika in Hungary in the mid-1990s to improve the color, causing lead poisoning in many consumers. Lead chromate is another lead-based pigment that has been used to add color to spices. In 2017, ground cumin was recalled in the United States due to “lead contamination,” which was determined by the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets to be lead chromate.

However, there is also an issue with lead contamination of agricultural products due to environmental contamination and uptake from the soil. Therefore, when recalls are posted for spices due to “elevated lead levels,” it may not immediately be apparent if the lead was due to environmental factors or intentionally added for color.

Laboratory methods for detecting the form of lead present in food are challenging. Typical tests look to detect lead, but do not necessarily identify the form in which it occurs. Testing for lead chromate, specifically, may be inferred through a test for both lead and chromium, and recent studies have looked at the development of more specific methods. There is not currently an FDA-established guideline for lead levels in spices although, the maximum allowable level for lead in candy is 0.1 ppm (0.00001%). New York State recalls spices with lead over 1 ppm and a Class 1 recall is conducted with lead over 25 ppm.

Two recent public health studies have evaluated lead poisoning cases and have linked some of those cases to consumption of contaminated spices. One study, published earlier this year, analyzed spice samples taken during lead poisoning investigations in New York over a 10-year period. The investigators tested nearly 1,500 samples of spices (purchased both domestically and abroad) and found that 31% of them had lead levels higher than 2 ppm. This study found maximum lead levels in curry of 21,000 ppm, in turmeric of 2,700 ppm, and in cumin of 1,200 ppm.

Another study conducted in North Carolina looked at environmental investigations in homes and testing of various products related to 61 cases of elevated lead levels in children over an eight-year period. The investigators found lead above 1 ppm in a wide variety of spices and condiments, with some levels as high as 170 ppm (in cinnamon) and 740 ppm (in turmeric).

A separate study, conducted in Boston, involved the purchase and analysis of 32 turmeric samples. The researchers detected lead in all of the samples (with a range of 0.03-99.50 ppm), with 16 of the samples exceeding 0.1 ppm (the FDA limit for lead in candy). The paper concluded that turmeric was being “intentionally adulterated with lead” and recommended additional measures on the part of FDA to reduce the risk of lead-contaminated spices entering the U.S. market and the establishment of a maximum allowable level of lead in spices.

Although the above studies did not report the form of lead detected, the high level of lead in many of the samples is not consistent with environmental contamination. A newspaper report in Bangladesh indicated that turmeric traders used lead chromate to improve the appearance of raw turmeric and quoted one spice company as saying that some of their suppliers admitted to using lead chromate. Lead consumption can be extremely toxic, especially to children. There is evidence that lead contamination of spices in the United States is an ongoing problem and that some of it is due to the intentional addition of lead-based pigments for color. This should be one area of focus for industry and regulatory agencies to ensure we reduce this risk to consumers.

*Given the nature of food fraud, it is fair to say that the data we collect is only the tip of the food fraud “iceberg”. Therefore, while this data indicates that these ingredients are prone to fraud in a number of ways, we cannot say that these numbers represent the true scope of fraud worldwide.