The demand for fish oil is increasing. It is packed full of heart-friendly omega-3 fatty acids, including the functionally important docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). Today, consumers are ever more aware of the health benefits of incorporating fish oil into their diets, such as lowering blood pressure and helping prevent heart disease. It is therefore no surprise that many companies are increasing their investments in providing high-quality fish oil supplements, such as those with value claims including single species, designated geographical origin, sustainability practices and traceability. And it’s a lucrative business: the industry was worth USD 11.95 Billion in 2021 and is expected to reach a value of USD 17.64 Billion by 2028—a CAGR of around 6.7%.

As the industry continues to grow, so does the risk of economic fraud. Fish oil itself varies depending on its source: fish from different regions—even within the same species—have different oil compositions, and, understandably, different price points depending on the quality. Individuals and illicit organizations are exploiting the growing demand by circulating adulterated, mislabeled products with sub-standard fish oil and/or misrepresented product origin for financial gain. More than ever, robust legislation is required, and there is a need for increasingly accurate and sensitive analytical techniques to verify the origin, authenticity and label claims of supplements, foods and beverages containing fish oils.

Traditional food integrity techniques can’t accurately distinguish the origin of fish oils from the same species. New approaches are needed to provide greater analytical depth and accuracy, and to ensure that consumers can trust brands, manufacturers are protected and governments can control the use of fish oil. Here we explore how gas chromatography isotope ratio mass spectrometry coupled with a mass spectrometer (GC-MS-IRMS) can overcome these challenges and allow analysts to confidently determine fish oil origin from a given species.

Fish Oils: A Tricky Catch for Authenticity Testing Laboratories

The existing approaches to determine fish oil authenticity, including gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) fatty acid profiling and untargeted fingerprint determination by spectroscopic techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and near-infrared (NIR), are based on the compositional characteristics of the oils. While these compositions are important to understand, they do not reflect significant regional and geographic parameters. Yet gaining clarity on the geographical origin of fish oils from the same species is vital because the source of the fish oil can have significant financial implications. In particular, label claims that fish oils are derived from a certain geographical region can add value to the product. Confirming the fish oil origin also verifies traceability of the product and contributes to other important label claims including sustainability, health and safety. Therefore, knowing the origin of the fish oil and its authenticity helps to identify fraudulent practices that are used to boost product value.

Isotope Fingerprints Identify Regions and Processes

So, how can we better characterize fish oil? Compound-specific stable isotope analysis (CSIA) is an ideal solution. Fatty acids consist almost entirely of carbon and hydrogen. In fish, the natural variation of the isotopic ratios of these elements is influenced by the feed, the environment and the local habitat of a given population. CSIA can enhance fish oil testing by determining the stable isotopic values of individual fatty acids. Since isotopes vary with differing dietary sources, geographical regions of origin can be determined, even within the same species.

Recent advances in GC-IRMS allow the technique to provide the separation accuracy and detection resolution required to distinguish between different carbon and hydrogen isotopes in compositionally equivalent fatty acids, by CSIA. GC-IRMS works by separating compounds using gas chromatography, then analyzing carbon and nitrogen isotope fingerprints by combustion, and oxygen and hydrogen isotope fingerprints through pyrolysis. This approach enables the acquisition of isotopic information for each individual compound in the sample.

To further improve the capability of GC-IRMS, the set-up can be coupled to a single quadrupole mass spectrometer—GC-MS-IRMS—to allow structural determination and identification of compounds. With the hybrid system, the flow from the GC column is separated into two parts: the majority continuing for IRMS isotope analysis, with a minor portion for MS compound identification. The innovative design does not impact IRMS sensitivity, thereby gaining structural information without compromise. These system attributes mean that GC-MS-IRMS can determine the structure and isotope ratio of each fish oil compound. Using this method, analysts can generate accurate (close to the absolute value), repeatable and reproducible results.

The power of GC-IRMS is well-established in the industry. It has been embraced as a method to be standardized in food authenticity testing by several international bodies, including the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) and the German Chemical Society (GDCh), and is only made more powerful when coupled to MS. However, standardization requires successful method validation, demanding its specific investigation for fish oil characterization.

Separating Salmon and Comparing Cod

Fish oil labeling is centered around differentiating species and their geographical origins to support label claims. In a recent experiment, Thermo Fisher Scientific and Imprint Analytics worked together with Orivo to compare 30 salmon oils and 43 cod liver oils from the same species in different areas. These experiments were performed to demonstrate that isotopes can be used to identify the geographic origin of the samples, and to validate the method.

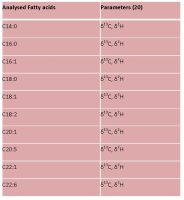

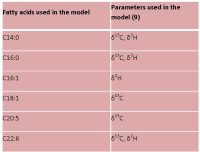

Samples were prepared by a derivatization procedure using CH3COCl in MeOH to obtain Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs). Both carbon and hydrogen isotopes were measured for the samples (Table 1), and statistical analysis of the isotope data allowed the selection of certain parameters for the statistical model (Table 2). These then contributed to the discrimination of the given clusters for each model.

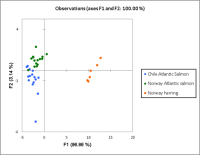

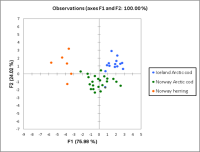

A number of principal functions (Fx) are generated in the analysis, integrating information from analytical parameters. Using different Fxs allows bivariate or multivariate illustrations, where F1 and F2 represent the largest amount of information available for the samples.

Table 1: List of the fatty acids (as FAMEs) screened and analyzed by GC-MS-IRMS.

Table 2: List of the fatty acids (as FAMEs) used in the statistical model.

Salmon

Most salmon products come from either Norway or Chile, and the two have significant price differences and values. It is therefore crucial that the label claims of any fish oil supplement can be verified. In the study, FAMEs were analyzed, and carbon and hydrogen isotope ratios determined using GC-MS-IRMS.

Discriminant analysis gave a correct prediction of 94.29% (Figure 1), showing that the two regional products could be clearly determined.

Figure 1: Discriminant analysis: Atlantic salmon (Norway) vs. Atlantic Salmon (Chile). Correct prediction: 94.29%

Cod

Similar to the salmon situation, Iceland and Norway have price discrepancies between products derived from each region’s cod. However, the two countries are physically very close, meaning there may be less extreme differences between the two diets and habitats, and therefore more similarity between isotopic fingerprints.

Despite the close proximity of the cod species, the multi-isotope method was able to discriminate the fish oil origin with a correct prediction of 97.22% (Figure 2). Based on this score, we can see the technique is highly accurate and reliable, making it a strong choice for fish oil determination.

Figure 2: Discriminant analysis: Arctic cod (Iceland) vs. Arctic cod (Norway). Correct prediction: 97.22%

GC-MS-IRMS Paves the Way for More Reliable Analyses of Fish Oil Authenticity

GC-MS-IRMS is a powerful technique that can determine the origin of fish oil by elucidating structure and isotope ratio. The study here shows the potential of GC-MS-IRMS in verifying the geographical origin of matrices with emerging commercial value and high adulteration risks—and validates the method, demonstrating that the resulting data provides conclusive answers about fish oil origins. Crucially, the technique is suitable even for products deriving from geographic regions close to one another.

We anticipate that isotope fingerprint analysis will continue to grow in the industry. With plans to use the technique to discriminate between different fish species underway, adopting GC-MS-IRMS methods into food analysis supports the need to uphold product authenticity and maintain consumer trust.

The authors kindly thank Orivo for collaboration on this study and providing the samples for analysis.