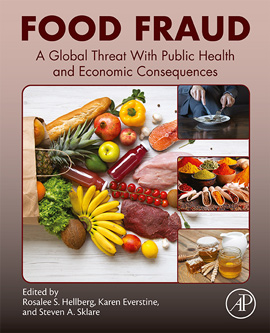

Food fraud is a global problem, the size of which cannot be fully quantified. A new book edited and authored by experts on the topic seeks to comprehensively address food fraud, covering everything from its history and mitigation strategies, to tools and analytical detection methods, to diving into fraud in specific products such as ingredients, meat, poultry and seafood.

“As we point out in the first sentence of the introduction to Food Fraud: A Global Threat with Public Health and Economic Consequences, food fraud prevention and risk mitigation has become a fast-evolving area. So fast, in fact, that some people may question the value of publishing a comprehensive resource focused on these issues for fear that it will be outdated before the ink is dry. The co-editors of the book disagree,” says Steve Sklare, president of The Food Safety Academy, chair of the Food Safety Tech Advisory Board and co-editor of the book. “This book was written with the goal of providing a solid resource that is more than an academic exercise or reference. The discussion of the fundamental principles of food fraud mitigation and real-world application of this knowledge will provide a useful base of knowledge from which new information and new technology can be integrated.”

Sklare co-edited the book with Rosalee Hellberg, Ph.D., associate director of the food science program at Chapman University and Karen Everstine, Ph.D., senior manager of scientific affairs at Decernis and member of the Food Safety Tech Advisory Board. He hopes that offering access to the book’s first chapter will help communicate their message to the folks responsible for addressing food fraud, whether they are members of the food industry, regulators or academics, or professionals at small, medium or large food organizations.

Complimentary access to Chapter 1 of Food Fraud: A Global Threat with Public Health and Economic Consequences is available in the Food Safety Tech Resource Library. The preview also includes the book’s Table of Contents.