Globally, milk and dairy products rank among the top eight allergens that affect consumers across the world. In America in particular, 32 million people suffer from some form of allergy, of which a staggering 4.7 million are allergic to milk. Additionally, it is estimated that around 70% of adults worldwide have expressed some form of lactose intolerance. As such, it is important for key stakeholders in the dairy industry to create novel products that meet the wants and needs of consumers.

Low-lactose products have been available since the 1980s. But in recent years, the demand for plant-based alternatives to dairy products has been on the rise. Some of this demand has come from individuals who cannot digest lactose or those that have an allergy to dairy. However, as all consumers continue to scrutinize their food labels and assess the environmental and ethical impact of their dietary choices, plant-based milk has become an appealing alternative to traditional dairy products.

To adapt to this changing landscape, traditional dairy processors have started to create these alternatives alongside their regular product lines. As such, they need access to instruments that are flexible enough to help them overcome the challenges of testing novel plant-based milk, while maintaining effective analysis and testing of conventional product lines.

David Honigs, Ph.D. will share his expertise during the complimentary webinar, “Supporting the Plant-Based Boom: Applying Intuitive Analytical Methods to Enhance Plant-based Dairy Product Development” | Friday, December 17 at 12 pm ETLow in Lactose, High in Quality

Some consumers—although not allergic to dairy—lack the lactase enzyme that is responsible for breaking down the disaccharide, lactose, into the more easily digestible glucose and galactose.

Low-lactose products first started to emerge in 1985 when the USDA developed technology that allowed milk processors to produce lactose-free milk, ice cream and yogurt. This meant consumers that previously had to avoid dairy products could still reap their nutritional benefits without any adverse side effects.

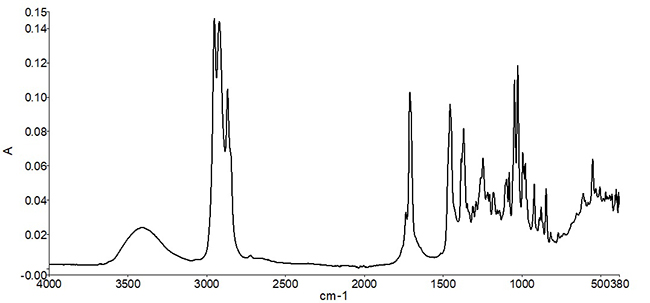

Similar to conventional dairy products, routine in-process analysis in lactose-free dairy production is often carried out using infrared spectroscopy, due to its rapid reporting. Additionally, the wavelengths that are used to identify dairy components are well documented, allowing for easier determination of fats, proteins and sugars.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) technologies are the most popular of the infrared spectroscopy instruments used in dairy analysis. As cream is still very liquid, even at high solid levels, FTIR can still effectively be used for the determination and analysis of its components. For products with a higher percentage of solids—usually above 20%—near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy can provide much better results. Due to its ability to penetrate pathlengths up to 20 mm, this method is more suitable for the analysis of cheeses and yogurts. For low-lactose products in particular, FTIR technology is integral to production, as it can also be used to monitor the breakdown of lactose.

Finger on the Pulse

For some consumers, dairy products must be avoided altogether. Contrary to intolerances that only affect the digestive system, allergies affect the immune system of the body. This means that allergenic ingredients, such as milk or dairy, are treated as foreign invaders and can result in severe adverse reactions, such as anaphylactic shock, when ingested.

From 2012 to 2017, U.S. sales of plant-based milk steadily rose by 61%. With this increasing demand and the need to provide alternatives for those with allergies, it has never been a more important time to get plant-based milk processing right the first time. Although the quantification of fat, protein and sugar content is still important in these products, they pose different challenges to processors.

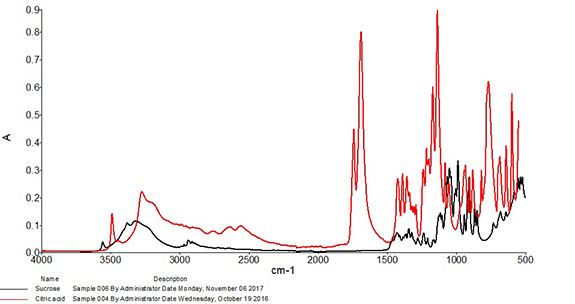

In order to mimic traditional dairy products, plant-based milk is often formulated with additional ingredients or as a blend of two plant milks. Sunflower or safflower oil can be added to increase viscosity and cane syrup or salt may be added to enhance flavor. All of these can affect the stability of the milk, so stabilizers or acidity regulators may also be present. Additionally, no plant milk is the same. Coconut milk is very high in fat content but very low in protein and sugar; on the other hand, oat milk is naturally very high in carbohydrates. This not only makes them suitable for different uses, but also means they require different analytical procedures to quantify their components.

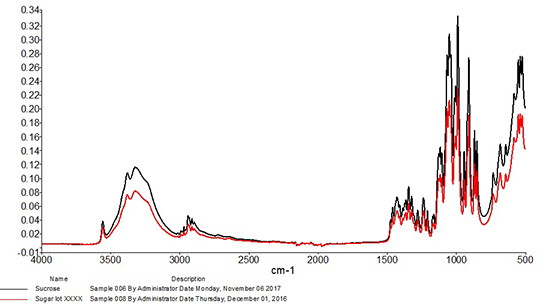

Although many FTIR and NIR instruments can be applied to plant-based milk in the same way as dairy milk, the constantly evolving formulation differences pose issues to processors. For example, the way that protein is determined in dairy milk will vary from the way protein is determined in almond milk. Both will follow a method of quantifying the nitrogen content but must be multiplied by a different factor. To help overcome these challenges, many companies have started to develop plant-based milk calibrations that can be used in conjunction with existing infrared instruments. Currently, universal calibrations exist to determine the protein, fat, solids, and sugar content of novel products. With more research and data, it’s likely in the future these will be expanded to generate calibrations that are specific to soy, almond and oat milk.

Even with exciting advancements in analytical testing for plant-based milk, the downtime for analysis is still a lot higher than traditional dairy. This is due to the increased solid content of plant-based milk. Many are often a suspension of solid particles in an aqueous solution, as opposed to dairy milk, which is a suspension of fat globules in aqueous solution. This means processors need to factor in additional centrifuge and cleaning steps to ensure results are as accurate and repeatable as possible.

In addition to the FTIR and NIR instruments used for traditional dairy testing, plant-based milk can also benefit from the implementation of diode array (DA) NIR instruments into existing workflows. With the ability to be placed at- and on-line, DA instruments can provide continual reporting for the constituent elements of plant-based milk as they move through the processing facility. These instruments can also produce results in about six seconds, compared to the 30 seconds of regular IR instruments, so are of great importance for rapid reporting of multiple tests across a day.

Keeping It Simple

Although the consumption of dairy-free products is on the rise, lots of plant-based milk are also made from other allergenic foods, such as soy, almonds and peanuts. Therefore, having low-lactose alternatives on the market is still valuable to provide consumers with a range of suitable options.

To do this, dairy processors and new plant-based milk processors need access to instruments that rapidly and efficiently produce accurate compositional analysis. For dairy processors who have recently started creating low-lactose or dairy-free milk alternatives, it is important that their instrumentation is flexible and used for the analysis of all their product outputs.

Looking towards the future, it’s likely both dairy products and their plant-based counterparts will have a place in consumers’ diets. Although there is some divide on which of these products is better—both for the environment and in terms of health—one thing that will become increasingly more important is the attitude towards the labeling of these products. Clean labels and transparency on where products are coming from, and the relative fat, protein and sugar content of foods, are important to many consumers. Yet another reason why effective testing and analytical solutions need to be available to food processors.