Food safety professionals often work behind-the-scenes, developing the systems and processes that keep our food supply free of harm. While a vital job, it’s often thankless work—recognition only comes when there’s a recall or an outbreak.

And yet, the food safety industry is evolving rapidly. New threats are emerging, new technologies are being deployed, and new regulations are causing changes in our fundamental infrastructure. “Good enough” pathogen detection is no longer good enough. As a result of new pressures, the food safety lab is emerging as one of the most promising centers of innovation in the entire supply chain. It’s time that the people who are driving this wave of innovation and change receive the positive recognition for their work that they deserve.

That’s why we’re starting this Q&A series—to hear the success stories, the best practices, the hurdles and the achievements from the best in the industry. We will dive deep with the experts into some of the biggest challenges and opportunities our industry faces, focused particularly on new technology that is advancing the industry by leaps and bounds—from blockchain to NGS to machine learning. As this series evolves, we hope that readers will be informed and inspired by what the future holds.

For our first interview, I had the pleasure of interviewing Bob Baker, corporate food safety science and capability director at Mars, Inc.. Bob leads the corporate food safety science strategy for Mars, Incorporated and provides leadership and consultation on food safety capability development and current and future challenges impacting global food security. Prior to his current role, Bob was responsible for the design, construction and leadership of the Mars Global Food Safety Center in Beijing, China.

Mahni Ghorashi: What are the biggest risks to our food safety infrastructure in 2018? What’s keeping you up at night?

Bob Baker: Food safety risks are increasing at an unprecedented rate, with new threats and hazards constantly emerging, changes in agricultural practices and food production, and the environment. The globalization of trade means that an issue in one part of the world often impacts the global supply chain.

To ensure safer food for all, the identification and isolation of potential and developing issues needs to happen at a much faster pace. At Mars, we believe industry has a crucial role to play in helping all stakeholders in the food supply chain identify risks and solutions, but no entity can do this alone. That’s why we have advocated for a new approach to food safety, one rooted in knowledge sharing and collaboration. That’s why we launched our Global Food Safety Center (GFSC) in 2015.

GFSC is conducting original research and collaborating in a number of areas that we see as critical—mycotoxin management, rapid detection and identification of pathogens, raw material and product authenticity, operational food safety optimization and transforming food safety through data integration.

Although we see improvements in some areas, some of them are becoming more complex. Mycotoxins are a prime example of that. Food fraud is another area of growing concern, and addressing that is going to take a focus on technology, regulation and enforcement and a number of other areas to deliver transparency, to verify sourcing, and ultimately ensure that customers and consumers are purchasing and consuming safe food.

Ghorashi: What are you most excited about? What’s changing in a good way in the food safety sector?

Baker: What’s encouraging is we’re seeing is a willingness to share information. At Mars we often bring together world experts from across the globe to focus on food safety challenges. We continue to see great levels of knowledge sharing and collaboration.

There are also new tools and new technologies being developed and applied. Something we’re excited about is a trial of portable ‘in-field’ DNA sequencing technology on one of our production lines in China. This is an approach that could, with automated sampling, reduce test times.

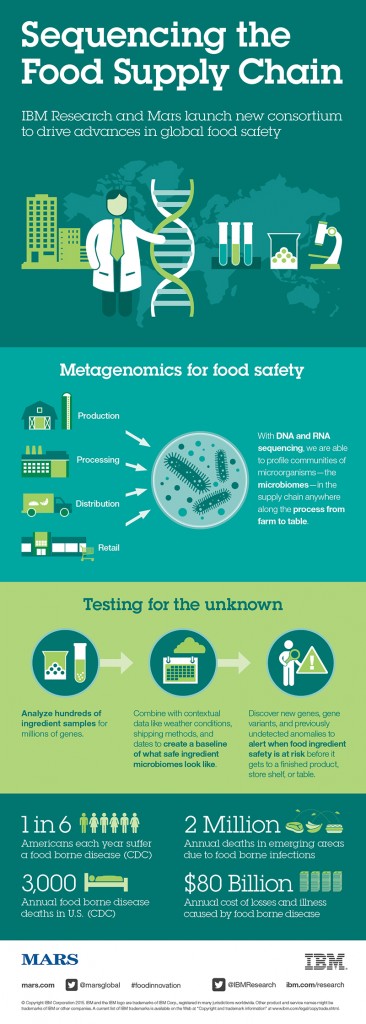

We’re also excited about the IBM-Mars Consortium for Sequencing the Food Supply Chain—early signs have been very encouraging. This is an approach that could change the nature of food safety management, taking us from testing for a specific pathogen, to a situation where we could map the entire makeup of an environment and predict food safety issues based on changes within that environment.

Ghorashi: If you take a look at the homepage of any of the food safety trade publications, all you see is recall after recall. Are transparency and technological advancement bringing more risks to light, and are things generally trending towards improvement?

Baker: At Mars, quality is our first principle and we take it seriously—if we believe that a recall needs to be made in order to ensure the safety of our consumers then we will do it. We also share lessons from recalls across our business to ensure that we learn from every experience.

Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a safe place for businesses to share such insights with each other. So although we are seeing more collaboration in the field of food safety generally, critical knowledge and experience from recalls is not being shared more broadly which may be having an impact.

Regarding the role of technological advancement, the hope is that as better tools and more advanced technology become available, it will be easier to pinpoint issues in the food supply chain much more effectively and much earlier than before which can only be a good thing.

Ghorashi: Do you see 2018 as the year when NGS technologies will find widespread adoption for food-safety testing applications? What can government and industry do to help accelerate adoption?

Baker: Next-generation sequencing has a lot of potential, but it may take time to be adopted fully.

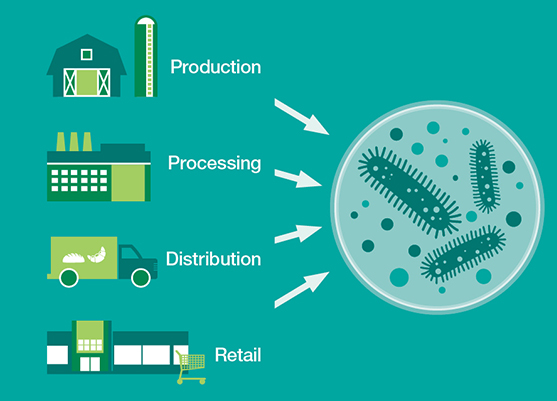

We are very pleased to see the U.S. government continue to view food safety as a priority. The FDA and the CDC are already moving from single-cell cultures and single genes to mixed genomics and metagenomics. At Mars, we see metagenomics as the future of food safety because it may help identify sentinels of food safety and predict potential issues through microbiome shifts.

The key to the development and adoption of any successful technology is sharing knowledge so that all parties from the government, industry and NGOs can build on it. Early results from the IBM-Mars Consortium for Sequencing the Food Supply Chain have been encouraging and we are actively sharing these initial insights via publications and scientific forums.

Ghorashi: What are some new technology processes on the horizon for 2018, and where should industry and government be investing its time and resources?

Baker: Food safety challenges are increasing, and we need to collaborate and share insights if we are to ensure safe food.

One major area is informatics and how we can enable better application of data mining, more applied bioinformatics and statistics. How can key players –regulators, industry, NGOs—get together and share data? How do you better mine data to move to a predictive model? This is an area that could benefit from a more focused approach between government and industry.

Ghorashi: What is your #1 goal for the industry in 2018? Fewer recalls? New tech implementation? Better regulatory oversight?

Baker: We’d like to see progress in all of the above, and we will continue to work with a range of stakeholders to move the needle on food safety.

That said, the food safety challenges facing us all are complex and evolving. Water and environmental contaminants are areas that industry and regulators are also looking at, but all of these challenges will take time to address. It’s about capturing and ensuring visibility to the right insights and prioritizing key challenges that we can tackle together through collaboration and knowledge sharing.