Safety is defined as controlling exposure for self and others. Going into 2020, the food industry battled safety concerns such as slips and falls, knife cuts, soft-tissue injuries, etc. As an “essential industry”, food-related organizations now face a unique challenge in controlling exposure to COVID-19. Not only must they keep their facilities clean and employees safe, they must also ensure they do not create additional exposures for their suppliers or customers.

These challenges increase at a time when employees may be distracted by stress, financial uncertainties, job insecurity, and worry for themselves and their families. Additionally, facilities may be understaffed, employees may be doing tasks they do not normally do, and we have swelling populations working from home.

While there is much we cannot control with COVID-19, there are specific behaviors that will reduce the risk of viral exposure for ourselves, our co-workers, and our communities. Decades of research show the power of behavioral science in increasing the consistency of safe behaviors. The spread of COVID-19 serves as an important reminder of what food-related organizations can gain by incorporating a behavioral component into a comprehensive exposure-reduction process.

Whether you have an existing behavior based safety process or not, follow these four steps.

Step 1: Pinpoint Critical COVID-19 Exposure Reduction Behaviors

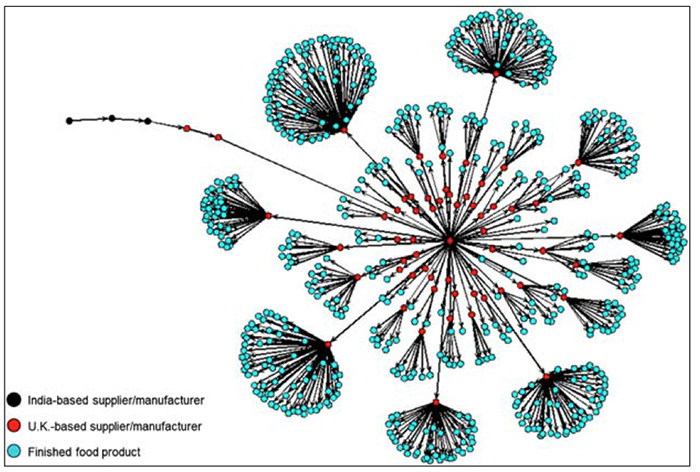

It is critical to clearly pinpoint the behaviors you want to see occurring at a high rate. In the food industry, an organization must control exposure both within their facilities as well as during interactions with suppliers and customers. Controlling exposure within facilities will typically include those behaviors recommended by the CDC such as:

- Maintain six feet of separation at all times possible.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth with unwashed hands.

- Minimize personal interactions to reduce exposure to transmit or receive pathogens.

- Frequent 20-second hand washing with soap and warm water.

- Make hand disinfectant available.

- Use alternatives to shaking hands.

- Frequently clean and disinfect common areas, such as meeting rooms, bathrooms, doorknobs, countertops, railings, and light switches.

- Sneeze and/or cough into elbow or use a tissue and immediately discard.

- Conduct meetings via conferencing rather than in person.

- If you are sick, stay home.

- If exposed to COVID-19, self-quarantine for precaution and protection of others.

Supplier/Customer exposure-reduction behaviors will vary depending upon your specific industry and may include pinpointing the critical behaviors for food preparation, loading dock delivery, customer home delivery, and customer pick up. When creating checklists to meet your unique exposures, be sure the behaviors you pinpoint are:

- Measurable: The behavior can be counted or quantified.

- Observable: The behavior can be seen or heard by an observer.

- Reliable: Two or more people agree that they observed the same thing.

- Active: If a dead man can do it, it is not behavior.

- Influenceable: Under the control of the performer.

Once you have drafted your checklists, ask yourself, “If everyone in my facility did all of these behaviors all the time, would we be certain that we were controlling exposure for each other, our suppliers, and our customers?” If yes, test your checklists for ease of use and clarity.

Step 2: Develop Your Observation Process

To do this, you will want to ask yourself:

- Who? Who will do observations? Can we leverage observer expertise from an existing process and have them focus on COVID-19 exposure reduction behaviors or should we create a new observer team?

- Where? Which specific locations, job types, and/or tasks should be monitored?

- When? When will observers conduct observations?

- Data: How will you manage the data obtained during the observations so that it can be used to identify obstacles to safe performance? Can the checklist items be entered into an existing database or will we need to create something new?

- Communication: What information needs to be communicated before we begin our COVID-19 Exposure Reduction process and over time? How will we communicate it?

Step 3: Conduct Your Observations and Provide Feedback

Starting the Observation

Your observers should explain that they are there to help reduce exposure to COVID-19 by providing feedback on performance.

Recording the Observation

Observers should note on the checklist which behaviors are occurring in a safe manner (protected) and which are increasing exposure to COVID-19 (exposed).

Provide Feedback

Feedback is given in the spirit of reducing exposure. It should be given as soon as possible after the observation to reinforce protected behaviors and give the person to opportunity to modify exposed behaviors.

Success Feedback

Success feedback helps reinforce the behaviors you want occurring consistently. Effective success feedback includes:

- Context: The situation in which the behavior occurred.

- Action: The specific behaviors observed which reduce exposure to COVID-19.

- Result: The impact of those behaviors on themselves or others—in this case, reduced COVID-19 exposure for themselves, their families and community.

“I care about your safety and do not want to see you exposed to COVID-19. I saw you use hand sanitizer prior to putting on eye protection. By doing that, you reduced the likelihood of transferring anything that might have been on your hands to your face which keeps you safe from contracting COVID-19.”

Guidance Feedback

Guidance feedback is given for exposed behaviors to transform that behavior into a protected one. Effective guidance feedback includes Context, Action, Result, but also:

- Alternative Action: The behavior that would have reduced their exposure to COVID-19.

- Alternative Result: The impact of that alternative behavior, such as reduced COVID-19 exposure for themselves, their families, and community.

“I care about your safety and do not want to see you exposed to COVID-19. I saw that you touched your face while putting on eye protection. By doing that, you increased the likelihood of transferring anything on your hand to your face which increases your risk of exposure to COVID-19. What could you have done to reduce that exposure?”

When giving guidance feedback, it is important to have a meaningful conversation about what prevented them from doing the safe alternative. Note these obstacles on the checklist.

Step 4: Use Your Data to Remove Obstacles to Safe Practices.

Create a COVID-19 exposure reduction team to analyze observation data. This team will identify systemic or organizational obstacles to safe behavior and develop plans to remove those obstacles. This is critical! When an organization knows that many people are doing the same exposed behavior, it is imperative that they not blame the employees but instead analyze what is going on in the organization that may inadvertently be encouraging these at-risk behaviors.

For example, we know handwashing and/or sanitizing is an important COVID-19 exposure reduction behavior. However, if your employees do not have access to sinks or hand sanitizer, it is not possible for them to reduce their exposure.

Similarly, the CDC recommends that people who are sick not come to work. However, if your organization does not have an adequate sick leave policy, people will come to work sick and expose their co-workers, customers and suppliers to their illness.

Your COVID-19 exposure reduction team should develop plans to remove obstacles to safe behavior using the hierarchy of controls.

Conclusion

Consistently executing critical behaviors is key to reducing exposure to COVID-19 as flattening the curve is imperative in the worldwide fight against this pandemic. Regardless of the type of behavior or the outcome that the behavior impacts, Behavior based safety systems work by providing feedback during the observations and then using the information obtained during the feedback conversation to remove obstacles to safe practices.

By using these tips, you can add a proven and powerful tool to your arsenal in the fight against COVID-19 and help keep your employees, their families, and your community safe.