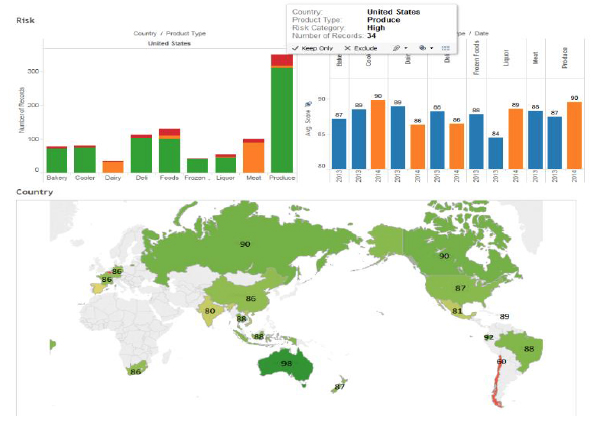

In February 2014, FDA published a Draft Approach for Designating High-Risk Foods under the Food Safety Modernization Act, with the purpose to identify high-risk foods based on specific parameters for additional recordkeeping requirements to enable rapid, effective tracking in the event of foodborne illness outbreak.

What are the factors by which a food is designated as ‘high-risk?” will FDA do such an analysis for every single food product? And what are concerns about this approach?

At a recent FSMA Fridays webinar, presented by SafetyChain, Dr. David Acheson and Jennifer McEntire, Ph.D., of The Acheson Group focused on this topic.

What will the high-risk foods list be used for?

Dr. David Acheson: What FDA wants to do with the high-risk foods list is to mainly leverage this for better product tracking. FDA will also have greater authority to ask for more information and keep more records for these high-risk foods, though the agency hasn’t clearly specified what information yet. Also the frequency of routine inspections for high-risk foods will be greater: once every three years, compared to once in every five years for non-high risk foods. One area which FDA hasn’t elaborated on is importers needing certificates for high-risk foods entering the U.S. Initially, the agency had considered this, but didn’t have a system in place to require this. Now the requirements are proposed in the FSMA rules and third-party audits can support this.

What are factors that will determine if a food is high risk?

Jennifer McIntyre: FDA considered several areas and has finalized a detailed methodology to identify high-risk foods based on the following parameters:

- Frequency of outbreak and occurrence of illness associated with that food since 1998;

- Severity of those illnesses;

- Likelihood of contamination;

- Growth potential of that food;

- Is there an opportunity during processing for that product to become contaminated;

- Consumption of that food product; and

- Economic impact associated with that food product in case there’s an outbreak or recall.

This approach is based on an evaluation of chemical and microbial hazards combined with foods using criteria that encompass the FSMA-required factors.

How will each food be scored and is there a distinguishing line between high-risk and non-high risk foods?

McEntire: Food will be rated on a 1 to 9 scale, with 1 being low, 3 being medium, and 9 being high. Companies have these three options to choose from. There’s no clear line the agency has proposed to determine what foods are on the list and what aren’t.

Is FDA going to do this analysis for every single food product? Where will they get the data from?

Acheson: There’s no way the agency can do this for every single food product. They are looking at a lot of parameters to consider. What they might do, and they are already doing, is try to bunch food products and commodities together, so there will be buckets of food identified as high-risk and non high-risk. Getting all that data will prove to be a challenge, considering that what’s available is quite thin. Private sector may have data that could help the agency, but then there’s the concern that if you share the data voluntarily, you have a risk of your product being classified as high-risk.

Are there any concerns being expressed in the industry about this approach?

McEntire: There are many concerns that industry is expressing right now, such as, given the limited data, how do you choose which foods to look at? How do you make sure that the analysis of one food can be applied to another food? How can we factor differences in processing and facilities? How will all the data be used? The parameters specify considering outbreaks going back to 1998 – some of this information has changed tremendously, and this will not factor in new regulations under FSMA.

One major concern is how can I get off the list? If you are considered a high-risk food now, but change your methodologies etc., can you get off the list? We need to see another iteration of this proposed rule from FDA to see if this rule can evolve and address some of these concerns.

What are some next steps for high-risk food methodology and what should industry do to prepare?

Acheson: Determining whether a food is high-risk or low risk will depend on the type of data being collected. The agency’s authority to increase demand for data for purposes of better tracking will require more robust data collection on the part of industry. Food companies will need to assess the data sets they are collecting now, and their product tracking system. Consider the IFT report and its recommendations to learn specifically what data should be collected. If a company determines that some of its products are going to be designated as high-risk, then they need to consider what the criteria will be for gaining that import certificate. Is that food being produced according to the standards that FDA is expecting? Pay attention to your foreign suppliers and ensure that they understand the need to be compliant with FSMA rules, and have sound food safety programs in place.

If this rule is a one-way street, where a food can only be moved from low-risk to being designated as ‘high-risk,’ then that would be disappointing and would detract from seeking improvement and rewarding behavior. The rule needs to consider situations when a company puts in specific mitigation steps in place, so can the food then be categorized as low risk?

For more details and to access FSMA Fridays webinars, please click here.

What lessons can you learn by looking at and analyzing your non-conformance reports and how can you use these to better your food safety management programs?

What lessons can you learn by looking at and analyzing your non-conformance reports and how can you use these to better your food safety management programs?