In today’s digital-first world, it might be surprising for those outside of the food manufacturing industry to learn that paper and pen are still considered state-of-the-art documentation tools. Answering food safety and quality questions such as: “What was the underlying cause of this customer complaint?” or “What caused the production halt this morning?” still require hours of research across paper documents, emails and spreadsheets. Maybe even the odd phone call or text message.

The good news is that many food safety and quality problems can be solved by leveraging modern-day technology. The challenge is taking that first step. By applying the following best practices, organizations can take small steps that lead to substantial benefits, including optimized food safety and quality programs, happier employees and safer operations.

Digital Transformation Best Practices

What if all the information food safety professionals require could be accessible through one unified interface and could proactively point to actions that should be taken? It can, with the right mindset and the right strategy.

While there is no “flip of a switch” to become digitally empowered, best practices exist for where to start. And, early adopters are injecting innovation into food safety programs with simple, but powerful technology.

Look Inward

Too often, food safety professionals push forward on a path to digital transformation by evaluating software and business applications against features and/or cost. But before taking this approach, it is important to look at existing food safety programs, identify where incremental improvements can be made and determine the potential return on a new technology investment.

Self-awareness is a beneficial leadership skill, but it’s also the key driver in understanding an organization’s business needs for food safety. Food safety professionals need to get real about common pain points, such as inconsistent or insufficient data, non-standardized practices, and delayed reporting. This is not the time to gloss over problems with processes or tools. Only by clearly documenting the challenges upfront will organizations be able to find the best solutions.

As one example, a common pain point is managing different formats and timing of reporting across facilities. See if this sounds familiar: “Well, Dallas sends an Excel spreadsheet every week, but Toledo only sends it on a monthly basis, while Wichita sends it monthly most of the time, but it’s never in the same format.”

Start out by identifying similar problems to help define the business objective, which will help determine how technology can be most effectively applied.

Eat, Sleep, Food Safety, Repeat

Food safety processes should constantly evolve to enable continued improvements in food safety outcomes. With that in mind, it’s helpful to dust off the corporate SOP and review it, especially if an organization is moving to a digital program. A common mistake many food manufacturers make is asking technology providers to configure an application based solely off the corporate protocol, only to discover at go-live that users don’t follow that protocol.

To avoid this situation, consider the following questions:

- Why are food safety professionals not completing processes by the book?

- Is that similar with every site?

- Why has it been that way for so long?

- Why did food safety professionals start to stray?

By locking down processes and identifying the desired way forward, leaders can configure a new application with the latest information and updated decisions. At a minimum, this step will help identify current issues that should be addressed, which can become measurable goals for the use of the new technology, ideally emphasizing the most pressing problems.

Less is More

Digital transformation doesn’t always need to become a “fix-all” project. Instead, it may revolve around a single operational initiative or business decision. For example, food safety professionals often maintain a spreadsheet with usernames and passwords for countless applications, some of which overlap in functionality and/or require a separate login for each facility. This is not only a safety concern, it’s an easy entry point when moving to a digital approach.

Consolidation of applications is a natural step from the standpoint of feasibility and fiscal responsibility. So, look for digital transformation opportunities that result in fewer applications and more consolidation.

Don’t Rush It

While digital transformation is inevitable, Rome wasn’t built in a day and neither should be an organization’s digital strategy. Unfortunately, the decision to go digital is often made, and a go-live date chosen, before determining what transformation requires, which is a clear-cut recipe for failure.

Technical vendors should play a key role in developing an effective implementation strategy, including sharing onboarding, planning, configuration and go-live best practices.

While technology is here to help the world become smarter about food safety, it is not here to replace human experience. Food safety leaders should continue to augment processes through supplemental technologies, rather than view technology as a full takeover of current approaches.

Barriers to entry for digital transformation are being lowered, as the ease of adoption of the underlying technologies continues to advance and access via cloud-based applications improves.

What to Do With All This Data? 5 Outcomes Food Manufacturers Can Achieve

Food manufacturers have benefited from digitally transforming environmental monitoring programs (EMPs) using workflow and analytics tools in a variety of ways. In the end, what matters is that the resulting data access and usability enables new insights and accelerates decisions that result in reduced risk and improved quality. Keep in mind these key outcomes that food manufacturers can achieve from digital transformation.

Outcome #1: Formalized Audit & Compliance Readiness

Enhancing an internal audit framework with digital tools will greatly reduce the burden of ensuring compliance for schemes such as BRC, SQF and FSSC food safety standards. Flexible report formats and filtering capabilities empower users with the right information at the right time.

Imagine, no more sifting manually through binders of CoA’s and test records to find a needle in a haystack. Exposing teams to a digital means of performing internal audits will not only boost confidence to handle requests from an auditor but will also help drive continuous improvement by providing easier access to insights about the effectiveness of internal policies. At the same time, digital tools will help ensure that only the required information is shared, reducing confusion and uncertainty as well as audit time and cost.

Outcome #2: Proactive Alerting and Automated Reporting

Threshold-based report alerts are an excellent way to reduce the noise often associated with notification systems. Providing quality and safety managers with automated alerts of scheduled maintenance or pending test counts can help them focus on activities that need attention, without distractions.

The benefit of threshold-based reporting is that it is a “set it and forget it” method. While regular “Monday Reports” are still a necessity, alerts and reports can be generated only when attention is needed for anomalies. A great example of this is being able to set proactive alerts for test counts in a facility that are approaching nonconformance levels. Understanding the corrective action requirements needed to control an environmental issue before it impacts quality, production and unplanned sanitation measures is a critical component of risk management and brand protection. In addition, reports can be automatically generated and delivered on a regular schedule to help meet reporting needs without spending time collecting data.

In other words—imagine a world where data comes and finds users when needed, rather than having to search for it in a binder or spreadsheet. Digital tools can provide email reports showing that a threshold has (or has not) been met and link the user directly to the information needed to take action. This is called “actionable information” and is something to consider when deploying technology within an organization’s food safety program processes.

Outcome #3: Optimize Performance with Tracking, Trending and Drilling

The Pareto Principle specifies that for many outcomes, about 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes. Historical data that is digitized can be used to quickly identify the root cause of top failures in a facility in order to drive process improvements. Knowing where to invest money will help avoid the cost of failure and aid in the prevention of a recall situation.

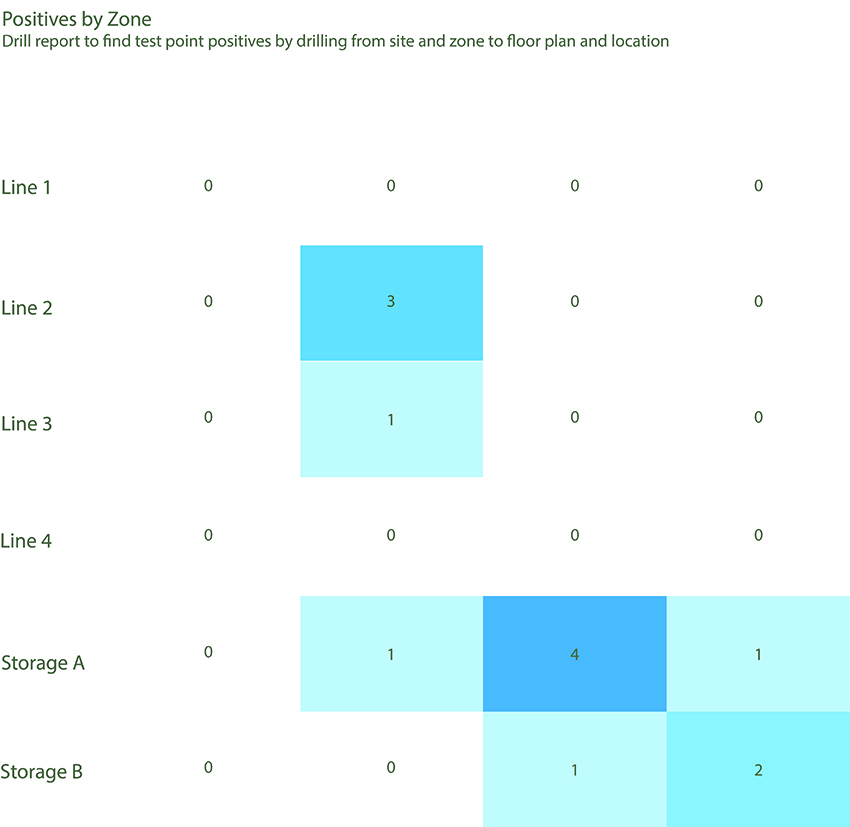

Dashboards are a powerful tool that organizations can use to understand the risk level across facilities to make better, data-driven decisions. Reports can be configured through a thoughtful dashboard setup that enables users to easily identify hot spots and trends, drill down to specific test locations, and enable clear communication to stakeholders. Figure 1 provides an example of a heat map that can be used to speed response and take corrective actions when needed.

Outcome #4: Simplified Data Governance and Interoperability

Smarter food safety will drive standardization of data formats, which allows information to flow seamlessly between internal and external systems. One of the major benefits of shifting away from paper-based solutions is the ability to be proactive to reduce risk and cost. FSQA managers, within and across facilities, can benefit from a 360-degree operational view that reveals hidden connections between information silos that exist in the plant and across the organization. This includes:

- Product tracing through product testing to environment monitoring and sanitation efforts

- Tracing back a product quality issue reported from a customer to the sanitation efforts

- Understanding why compliance is on track but quality results aren’t correcting

Outcome #5: Reduce the Cost of High Turnover

Successful GMPs, SSOPs and a HACCP program require leaders that continually ensure that employees are properly trained, which can be difficult with high turnover rates. To address this challenge, digital tools can aid in providing easily accessible documentation to empower users and reduce the cost, time and risk associated with having to re-train new employees on the EMP process. While training cannot be replaced with technology, it can be accelerated.

For example, testing locations within facilities can be documented with images and related information enabling new employees to visually see the floorplan and relevant testing protocols with accompanying video and click-through visualization of underlying data. Additionally, corrective action protocols can be enhanced with videos and standardized form inputs to ensure proper data is being collected at all times.

The Path Ahead

As the digital transformation of the food safety industry continues, food manufacturers should seek out and apply proven best practices to make the process as efficient and effective for their organization as possible. By avoiding common pitfalls, companies can achieve transformation objectives and realize substantial benefits from more easily accessible and actionable food safety data.