While foodborne transmission of the novel coronavirus is unlikely , the virus has significantly affected all aspects of food production, food manufacturing, retail sales, and foodservice. The food and agriculture sector has been designated as a “critical infrastructure,” meaning that everyone from farm workers to pest control companies to grocery store employees has been deemed essential during this public health crisis.* As a society, we need the food and agriculture sector to continue to operate during a time when severe illnesses, stay-at-home orders and widespread economic impacts are occurring. Reports of fraudulent COVID-19 test kits and healthcare scams reinforce that “crime tends to survive and prosper in a crisis.” What does all of this mean for food integrity? Let’s look at some of the major effects on food systems and what they can tell us about the risk of food fraud.

Supply chains have seen major disruptions. Primary food production has generally continued, but there have been challenges within the food supply chain that have led to empty store shelves. Recent reports have noted shortages of people to harvest crops, multiple large meat processing facilities shut down due to COVID-19 cases, and recommendations for employee distancing measures that reduce processing rates. One large U.S. meat processor warned of the need to depopulate millions of animals and stated “the food supply chain is breaking.” (An Executive Order was subsequently issued to keep meat processing plants open).

Equally concerning are reports of supply disruptions in commodities coming out of major producing regions. Rice exports out of India have been delayed or stopped due to labor shortages and lockdown measures. Vietnam, which had halted rice exports entirely in March, has now agreed to resume exports that are capped at much lower levels than last year. Other countries have enacted similar protectionist measures. One group has predicted possible food riots in countries like India, South Africa and Brazil that may experience major food disruption coupled with high population density and poverty.

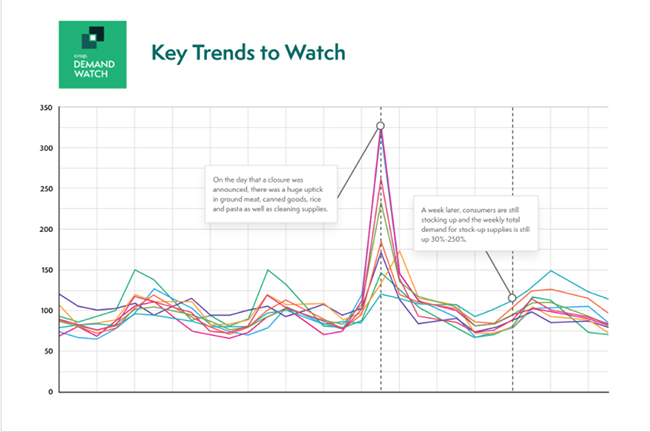

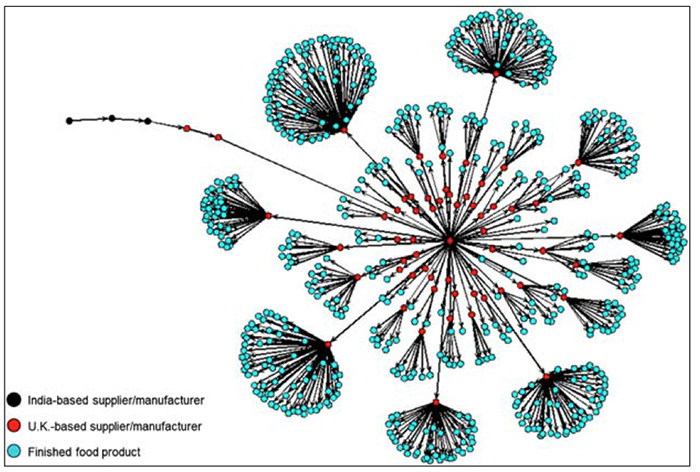

Supply chain complexity, transparency and strong and established supplier relationships are key aspects to consider as part of a food fraud prevention program. Safety or authenticity problems in one ingredient shipment can have a huge effect on the market if they are not identified before products get to retail (see Figure 1). Widespread supply chain disruptions, and the inevitable supplier adjustments that will need to be made by producers, increase the overall risk of fraud.

Regulatory oversight and audit programs have been modified. The combination of the public health risk that COVID-19 presents with the fact that food and agriculture system workers have been deemed “critical” has led to adjustments on the part of government and regulatory agencies (and private food safety programs) with respect to inspections, labeling requirements, audits, and other routine activities. The FDA has taken measures including providing flexibility in labeling for certain menus and food products, temporarily conducting remote inspections of food importers, and generally limiting domestic inspections to those that are most critical. USDA FSIS has also indicated they are “exercising enforcement discretion” to provide labeling flexibilities. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) announced they are prioritizing certain regulatory activities and temporarily suspending those activities determined to be “low risk.” GFSI has also taken measures to allow Certification Program Owners to provide certificate extensions due to the inability to conduct in-person audits.

While these organizations have assured stakeholders and the public that food safety is of primary importance, the level of direct regulatory and auditing oversight has been reduced to reduce the risk of virus transmission during in-person activities. Strong auditing programs with an anti-fraud component are an important aspect of food fraud prevention. Adjustments to regulatory and auditing oversight, as necessary as they may be, increase the risk of fraud in the food system.

There is a focus on safety and sustainability of foods. The food industry and regulatory agencies are understandably focused on basic food safety and food sustainability and less focused on non-critical issues such as quality and labeling. However, there is a general sense among some in industry that the risk of food fraud is heightened right now. Many of the effects on the industry due to COVID-19 are factors that are known to increase fraud risk: Supply chain disruptions, changes in commodity prices, supplier relationships (which may need to be changed in response to shortages), and a lack of strong auditing and oversight. However, as of yet, we have not seen a sharp increase in public reports of food fraud.

This may be due to the fact that we are still in the relatively early stages of the supply chain disruptions. India reported recently that the Food Safety Department of Kerala seized thousands of kilograms of “stale” and “toxic” fish and shrimp illegally brought in to replace supply shortages resulting from the halt in fishing that occurred due to lockdown measures.

High-value products may be particularly at risk. Certain high-value products, such as botanical ingredients used in foods and dietary supplements, may be especially at risk due to supply chain disruptions. Historical data indicate that high-value products such as extra virgin olive oil, honey, spices, and liquors, are perpetual targets for fraudulent activity. Turmeric, which we have discussed previously, was particularly cited as being at high risk for fraud due to “‘exploding’ demand ‘amidst supply chain disruptions.’”

How can we ensure food sufficiency, safety, and integrity? FAO has recommended that food banks be mobilized, the health of workers in the food and agriculture sector be prioritized, that governments support small food producers, and that trade and tax policies keep global food trade open. They go on to say, “by keeping the gears of the supply chains moving and actively seeking international cooperation to keep trade open, countries can prevent food shortages and protect the most vulnerable populations.” FAO and WHO also published interim guidance for national food safety control systems, which noted the increased risk of food fraud. They stated “during this pandemic, competent authorities should investigate reported incidences involving food fraud and work closely with food businesses to assess the vulnerability of supply chains…”.

From a food industry perspective, some important considerations include whether businesses have multiple approved suppliers for essential ingredients and the availability of commodities that may affect your upstream suppliers. The Acheson Group recommends increasing supply chain surveillance during this time. The Food Chemicals Codex group recommends testing early and testing often and maintaining clear and accurate communication along the supply chain.1 The nonprofit American Botanical Council, in a memo from its Botanical Adulterants Prevention Program, stated “responsible buyers, even those with relatively robust quality control programs, may need to double- or even triple-down on QC measures that deal with ingredient identity and authenticity.”

Measures to ensure the sufficiency, sustainability, safety and integrity of foods are more closely linked than ever before. In this time when sufficiency is critical, it is important to avoid preventable food recalls due to authenticity concerns. We also need to stay alert for situations where illegal and possibly hazardous food products enter the market due to shortages created by secondary effects of the virus. The best practices industry uses to reduce the risk of food fraud are now important for also ensuring the sufficiency, sustainability and safety of the global food supply.

Reference

- Food Safety Tech. (April 24, 2020). “COVID-19 in the Food Industry: Mitigating and Preparing for Supply Chain Disruptions “. On-Demand Webinar. Registration page retrieved from https://register.gotowebinar.com/recording/1172058910950755596

*Foodborne transmission is, according to the Food Standards Agency in the U.K., “unlikely” and, according to the U.S. FDA, “currently there is no evidence of food or food packaging being associated with transmission of COVID-19.”