Moving forward, if food manufacturers, suppliers and distributors want to be ahead of the game, they’ll need to have the ability to view their product throughout the supply chain. During a discussion with Food Safety Tech, Trish Meek, director of product strategy at Thermo Fisher Scientific, explains the importance of product traceability in the food chain, from both a consumer and food producer’s perspective.

Food Safety Tech: In your recent article about Integrated Informatics, you cite it as an ideal solution to modernizing a highly distributed food chain. What are the challenges you see companies facing in managing their global supply chain?

Trish Meek: We’ve seen the issues related to intentional adulteration documented throughout the media, and they extend to traceability. For example, what Tesco experienced during the horsemeat scandal wasn’t necessarily intentional adulteration, but rather a matter of not understanding the supply chain. Horsemeat was introduced in France as legitimate meat and then it ended up in the UK. In this case, you have a lack of traceability and thus a lack of understanding of what has happened to your product in its lifecycle.

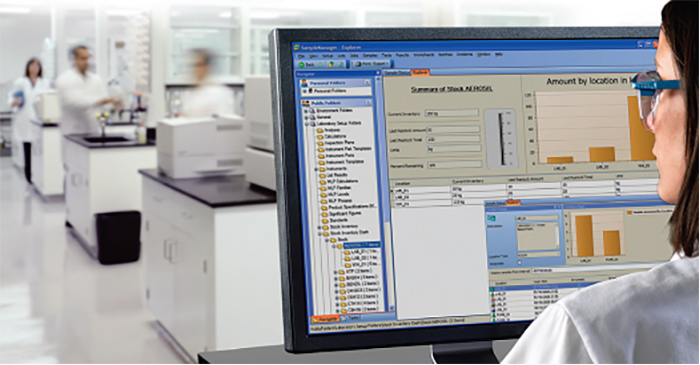

In this complex world of suppliers, distributors and food producers, having the ability to pull in analytical data and manage it regardless of the source (whether it’s from the initial ingredient supplier or the final manufacturer) is a critical piece in understanding the overall lifecycle picture. An integrated informatics solution provides a single source of truth for that information: From the technician operating the lab process to the lab manager who is overseeing to the integration into the enterprise-level system. It provides a complete view on everything that has happened to your data, while also enabling the management of regional specifications.

FST: What are the biggest concerns in the area of food chain security?

Meek: Traceability is key, and the common denominator is food chain security: Ensuring that you’re providing security and with an understanding of everything that happened to your product, which leads to quality assurance and brand security.

FST: What are the concerns related to food chain security?

Meek: There are a few concerns:

- Adulteration

- Correct label claims. For example, 30% of the populous is trying to avoid gluten. While 1% is truly allergic to it, there’s a lot of gluten intolerance. Take, for example, recent commercials from Cheerios saying they are ensuring traceability and can say with confidence that their product no longer comes into contact with wheat in any part of the process. There’s an understanding that consumers want to believe what’s on the label, from both a health and allergy perspective as well as a concern in the public around unhealthy ingredients added or antibiotics used. As a food producer, you want to make sure you can honestly state what has happened to the food and that what you’ve put on your label is true. People are willing to pay a premium, and so there’s a drive towards the premium of being able to claim no GMOs on a label or an organic product.

- From a food producer’s point of view, having traceability from all suppliers is key. They want to ensure that any raw materials have been handled and managed with all the same scrutiny and adherence to regulatory requirements as their own processes. With ingredients coming from all over the world, manufacturers are relying on multi-sourcing ingredients from places they don’t necessarily control, so they need to have the traceability before the ingredients appear in the final product.

|

Using an Integrated Informatics Platform Trish Meek: Through an integrated informatics platform, users can manage the entire lab process and integrate it into the enterprise system. Having the ability to incorporate the lab data is critical to ensuring product safety, quality and traceability throughout the entire supply chain. Because the solution encompasses lab processes and required lab functionalities, it enables efficiency both in the laboratory as well as across the entire operation. The solution provides an opportunity not just to the top-tier food producers but also the regionally based middle-tier companies that want to set themselves up for future growth. The reality of the regulations today is that you must look towards the future. Twenty years ago, we weren’t including information about what nuts were present in the labeling. Now there’s consumer awareness and a change in labeling. And five years from now, there could be a different allergy that needs to be documented in the labeling. Integrated informatics gives you the business agility to take on that next step of analysis and adapt to the marketplace. |