Every day, food industries around the world work to comply with the food labeling directives and regulations in place to inform consumers about specific ingredients added to finished products. Of course, special attention has been placed on ensuring that product packaging clearly declares the presence of food allergens including milk, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soy, sesame and mustard. (Additional food allergens may also be included in other regions.)

But labeling only covers the ingredients deliberately added to foods and beverages. In reality, food manufacturers have two jobs when it comes to serving the needs of their allergic consumers:

- Fully understand and clearly declare the intentional presence of allergenic foods

- Prevent the unintended presence of allergenic foods into their product

Almost half of food recalls are the result of undeclared allergens, and often these at-fault allergens were not only undeclared but unintended. Given such, the unintended presence of allergenic foods is something that must be carefully considered when establishing an allergen control plan for a food processing facility.

How? It starts with a risk assessment process that evaluates the likelihood of unintentionally present allergens that could originate from raw materials, cross-contact contamination in equipment or tools, transport and more. Once the risks are identified, risk management strategies should then be established to control allergens in the processing plant environment.

It is necessary to validate these risk management strategies or procedures in order to demonstrate their effectiveness. After validation, those strategies or procedures should then be periodically verified to show that the allergen control plan in place is continually effective.

In several of these verification procedures it may be necessary to utilize an analytical test to determine the presence or absence of an allergenic food or to quantify its level, if present. Indeed, selecting an appropriate method to assess the presence or the level of an allergenic food is vitally important, as the information provided by the selected method will inform crucial decisions about the safety of an ingredient, equipment or product that is to be released for commercialization.

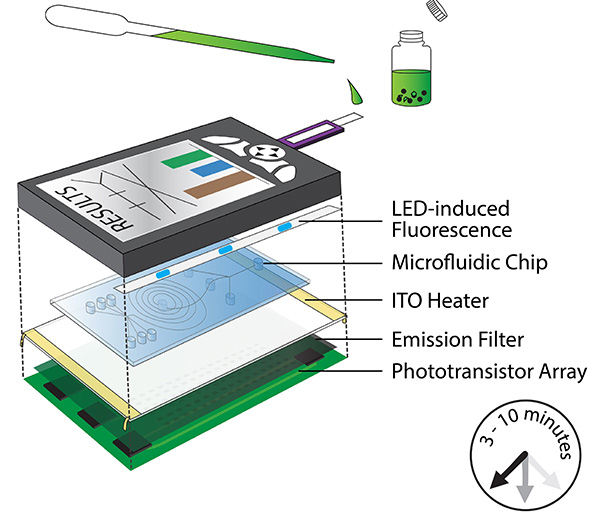

A cursory review of available methods can be daunting. There are several emerging methods and technologies for this application, including mass spectroscopy, surface plasmon resonance, biosensors and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Each of these methods have made advancements, and some of them are already commercialized for food testing applications. However, for practical means, we will discuss those methods that are most commonly used in the food industry.

In general, there are two types of analytical methods used to determine the presence of allergenic foods: Specific and non-specific methods.

Specific tests

Specific methods can detect target proteins in foods that contain the allergenic portion of the food sample. These include immunoassays, in which specific antibodies can recognize and bind to target proteins. The format of these assays can be quantitative, such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that may help determine the concentration of target proteins in a food sample. Or they can be qualitative, such as a lateral flow device, which within a few minutes and with minimum sample preparation can display whether a target protein is or is not present. (Note: Some commercial formats of ELISA are also designed to obtain a qualitative result.)

To date, ELISA assays have become a method of choice for detection and quantification of proteins from food allergens by regulatory entities and inspection agencies. For the food industry, ELISA can also be used to test raw ingredients and final food products. In addition, ELISA is a valuable analytical tool to determine the concentration of proteins from allergenic foods during a cleaning validation process, as some commercial assay suppliers offer methods to determine the concentration of target proteins from swabs utilized to collect environmental samples, clean-in-place (CIP) final rinse water or purge materials utilized during dry cleaning.

ELISA methods often require the use of laboratory equipment and technical skills to be implemented. Rapid-specific methods such as immunoassays with a lateral flow format also allow detection of target specific proteins. Given their minimal sample preparation and short time-to-result, they are valuable tools for cleaning validation and routine cleaning verification, with the advantage of having a similar sensitivity to the lowest limit of quantification of an ELISA assay.

The use of a specific rapid immunoassay provides a presence/absence result that determines whether equipment, surfaces or utensils have been cleaned to a point where proteins from allergenic foods are indiscernible at a certain limit of detection. Thus, equipment can be used to process a product that should not contain a food allergen. Some commercial rapid immunoassays offer protocols to use this type of test in raw materials and final product. This allows food producers to analyze foods and ingredients for the absence of a food allergen with minimum laboratory infrastructure and enables in-house testing of this type of sample. This feature may be a useful rapid verification tool to analyze final product that has been processed shortly after the first production run following an equipment cleaning.

Non-Specific Tests

While non-specific testing isn’t typically the best option for a cleaning validation study, these tests may be used for routine cleaning verification. Examples of non-specific tests include total protein or ATP tests.

Tests that determine total protein are often based on a colorimetric reaction. For example, commercial products utilize a swab format that, after being used to survey a defined area, is placed in a solution that will result in a color change if protein is detected. The rationale is that if protein is not detected, it may be assumed that proteins from allergenic foods were removed during cleaning. However, when total protein is utilized for routine verification, it is important to consider that the sensitivity of protein swabs may differ from the sensitivity of specific immunoassays. Consequently, highly sensitive protein swabs should be selected when feasible.

ATP swab tests are also commonly utilized by the food industry as a non-specific tool for hygiene monitoring and cleaning verification. However, the correlation between ATP and protein is not always consistent. Because the ATP present in living somatic cells varies with the food type, ATP should not be considered as a direct marker to assess the removal of allergenic food residues after cleaning. Instead, an analytical test designed for the detection of proteins should be used alongside ATP swabs to assess hygiene and to assess removal of allergenic foods.

Factors for Using One Test Versus Another

For routine testing, the choice of using a specific or a non-specific analytical method will depend on various factors including the type of product, the number of allergenic ingredients utilized for one production line, whether a quantitative result is required for a particular sample or final product, and, possibly, the budget that is available for testing. In any case, it is important that when performing a cleaning validation study, the method used for routine testing also be included to demonstrate that it will effectively reflect the presence of an allergenic food residue.

Specific rapid methods for verification are preferable because they enable direct monitoring of the undesirable presence of allergenic foods. For example, they can be utilized in conjunction with a non-specific protein swab and, based on the sampling plan, specific tests can then be used periodically (weekly) for sites identified as high-risk because they may be harder to clean than other surfaces. In addition, non-specific protein swabs can be used after every production changeover for all sites previously defined in a sampling plan. These and any other scenarios should be discussed while developing an allergen control plan, and the advantages and risks of selecting any method(s) should be evaluated.

As with all analytical methods, commercial suppliers will perform validation of the methods they offer to ensure the method is suitable for testing a particular analyte. However, given the great diversity of food products, different sanitizers and chemicals used in the food industry, and the various processes to which a food is subjected during manufacturing, it is unlikely that commercial methods have been exhaustively tested. Thus, it is always important to ensure that the method is fit-for-purpose and to verify that it will recover or detect the allergen residues of interest at a defined level.