Success Factor 3: Create exams that properly assess the workforce.

Food safety exams give employers the peace of mind that the employees they hire can do the job they were trained to do and help prevent food safety incidents from happening. Equipped with the right training and assessment developed by responsible and qualified companies, employees in the field―ranging from food handlers to food managers―are the first line of defense to uphold the highest of food safety and security standards.

My previous two columns in Food Safety Tech explained important factors that employers need to consider when developing a food safety assessment program. Working with a quality-driven food safety assessment provider to develop the exam is a critical first step. Equally important is the practice of using exams with rigorous, reliable and relatable questions that are developed, tested and continuously evaluated to correlate with market needs and trends.

This article focuses on another key factor that should not be overlooked. In order to properly assess the workforce, exams must reflect best practices for test taking and learning, and be in sync with how the workforce operates and processes information. It is not enough for food safety assessment providers to merely develop questions and exams. A comprehensive exam creation process that takes into consideration technical and human factors allows for a fair assessment of workers’ knowledge and skills, while also providing feedback on exam performance that can be used to adapt exams in an ever-changing industry.

What should employers look for to help ensure that exams can properly assess the food safety workforce?

First, food safety exams should test what a food safety worker needs to know, and quality-driven assessment providers should solicit input from the industry during the exam creation process. Test developers should use surveys, conduct interviews and facilitate panel-based meetings to gather information. They also should invest in close collaboration with industry-leading subject matter experts (SMEs), as well as food handlers, managers and regulators in order to create questions and exams that are relevant. By engaging SMEs during the question writing and exam creation process, qualified food safety assessment providers can pinpoint the important information to be developed into questions and implemented in the exams.

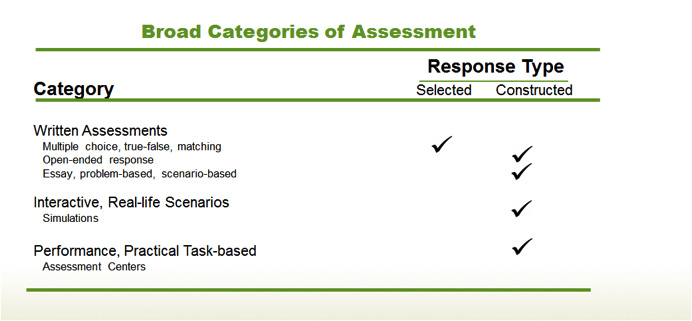

In addition to incorporating industry stakeholder input, it is important for assessment providers to have a comprehensive understanding of the various assessment modalities —from selected response item types, such as multiple choice assessments, to performance-based, interactive scenarios that mirror real-life situations—and select the appropriate modality to maintain test fidelity.

An assessment provider with this level of proficiency can leverage the combination of its expertise and industry awareness to determine the best modality for the food safety workforce. For example, progressive assessment providers are actively investing in interactive, animated, scenario-based assesments because they believe this type of testing might better assess the skills and knowledge required to successfully perform in the workplace while providing:

- High candidate engagement levels—with real-life scenarios being more relatable.

- A safe environment for candidates to practice and understand the consequences of their actions.

Another critical component in creating effective exams is for the assessment provider to continuously review the content and incorporate quantitative and qualitative feedback from data and test takers respectively. By reviewing feedback regularly, asssessment providers can enhance the exams and adjust accordingly—keeping the exam relevant to the workforce and the industry. As the workforce and the industry change, so should food safety exam and certification programs. A feedback loop is essential to help ensure that the exam stays relevant to those who work in the food service industry as they seek to prove that they have mastered the necessary principles and skills to protect the public against food incidents. If a food safety exam does not properly assess the workforce, the consequences can be significant, not only to public health and safety, but also to the companies preparing, handling and serving food that could experience loss of reputation, revenue and the business.

Quality-driven food safety assessment providers follow a best-practices approach for creating exams and certificate/certification programs. They demonstrate a thorough understanding of behavioral learning, the necesary job skills and regulatory compliance requirements. A food safety exam that properly assesses the workforce will:

- Solicit industry input.

- Incorporate interactive scenarios that mirror real-life situations.

- Create a feedback loop and adaptable exams that can easily be modified to stay abreast with the ever-changing industry.

While food handlers may be one of the biggest vulnerabilities in a safe food supply and delivery chain, they also represent one of the greatest opportunities to guard against food safety issues. Developing an effective food safety assessment program as part of a preventative strategy will help ensure both public health and corporate long-term business success.