Food fraud has been at the center of attention recently and has highlighted inconsistencies in the food industry and supply chain management. Both consumers and regulators are demanding or imposing new standards for assuring the authenticity of food products. In such a context, food industries have to use their knowledge, perceptions and experience to answer and comply with regulators, consumers, and (for some) GFSI requirements regarding food fraud management. However, one can ask how ready and aware food industry players are to understand, mitigate and tackle food fraud. With those questions in mind, the research team of the CIRANO at Montreal, Canada led by Professor Nathalie de Marcellis-Warin and the research team of the PARERA platform at Laval University, Quebec, Canada led by Professor Samuel Godefroy had developed a survey of 52 closed questions to assess the awareness and the perceptions of Canadian food industries toward food fraud and what actions they had already implemented to mitigate their risks. The survey included six main sections:

- Food fraud definition

- Perceptions of food fraud burden globally and locally

- Food fraud regulations

- Food industry responsibility towards food fraud

- Their capacities to prevent and manage this aspect of food quality and safety

- Food fraud prevention practices, detection methods and their implementation.

A total of 398 Canadian food industries took the survey; they were food processors, producers (crop, livestock, and fisheries), and distributors (agricultural wholesalers, wholesaler-merchants, and retailers). They will be referred to as Food Business Operators (FBOs) or processors, producers, and distributors when a difference was highlighted between sectors.

What Is the Level of Knowledge of Food Fraud?

Firstly, there is no current data on knowledge of food industry operators on food fraud, hence, the research team proposed definitions and the respondents had to identify which ones could refer to food fraud (1) An intentional and deliberate act (2) False or misleading statements for economic gain and (3) An act aimed at misleading the consumer. More than nine FBOs assigned the definitions to food fraud, hence showing a good understanding of what food fraud is. In an additional question some examples of food fraud were proposed:

- Hidden mix of a liquid with another liquid of lower quality

- Hidden information about a product or one of its ingredients

- Hidden replacement of a product or one of its ingredients by a product of lower quality

- Labeling containing false claims

- Addition of a non-approved or illegal ingredient.

Again, more than 90% of the FBOs were able to identify those cases as food fraud. The answers to the first questions suggested that Canadian FBOs understand what food fraud is.

Was Your Company a Victim of Fraud?

The authors asked the respondents if they think or know that their company has already been the victim of food fraud in the past or recently. Besides, the respondents were asked to assess how safe their company is towards food fraud. More than a third of the respondents reported to have been a victim of fraud in the past, but sectors answered differently. In fact, while 40% of processors and 48% of the distributors answered it was likely or very likely that their company had been a victim, only 24% of the producers gave this answer. In parallel, one third of the respondents agreed that their business is safe from food fraud, however, the results per sector were statistically different: 42% of the producers agreed while only a quarter of the processors and the distributors felt safe from food fraud. Those results indicated a shift between producers and the two other sectors; the producers seem to feel less impacted and concerned by food fraud.

Who Is Responsible for Managing Food Fraud?

Depending on where the FBO is in the supply chain, one can make the hypothesis that this company might not feel responsible for the authenticity of the products it buys or sells. The survey authors asked respondents if they considered themselves as responsible for the products’ authenticity they would buy or sell to consumers or an intermediate. Among the three sectors, 82% of the respondents considered themselves as responsible for the products they received from the suppliers, and 80% for the authenticity of the products they sell to consumers. However, only half consider they are responsible for the product authenticity once it is processed or sold by a client. It was reassuring to see that FBOs understand fraud and consider themselves as responsible for ensuring food authenticity. One can argue that this perception will positively impact the robustness of their mitigation measures and the controls of food fraud.

Which Measures Have Canadian FBOs Implemented to Prevent Food Fraud?

FBOs mainly implemented a supply chain traceability system to mitigate food fraud. This result was not surprising, as traceability has to be in place to comply with current requirements for food safety and food quality. The vulnerability assessment is a recommended (or required) procedure to implement in food industries to comply with regulations and certifications such as GFSI, and 36% of the FBOs have implemented this measure (half of the processors). Finally, detection methods were implemented by only 27% of respondents. Interestingly, through another question, those three measures were seen as the more efficient way to fight food fraud according to the respondents. Also, FBOs would rely on a stable and long-term relationship based on trust with their supplier to mitigate food fraud and rated this measure as an efficient way to fight food fraud. Audits of suppliers and ingredient authenticity checking were also perceived as efficient but were not implemented as frequently. The lack of human resources, financial means, training, and time were the reasons why processors and distributors did not implement more measures to counter food fraud. Interestingly, the primary reason producers selected was “the system in place was enough” followed by lack of financial means, human resources and time and “food fraud is not an essential stake for our company.” One can relate this difference between the sectors with the observation made earlier on how safe the producers feel compared to the two other groups. Regarding detection methods, 88% of the FBOs rated their knowledge of those technologies as moderate or low, and 77% of the respondents rated the frequency of food fraud detection technologies as “never to rarely”. The reason why detection methods are not applied more was the lack of financial means, and the system in place is adequate to control food fraud.

Also, If They Identify Fraud, What’s Next?

Lastly, the authors asked what the respondent would do if their company identified an incident of fraud. Most of the respondents (69%) said they would speak to their supplier; this affirmation can be associated with the strong and long-term relationship the company would have with the supplier. The second option chosen was to change the supplier and then inform the authorities. The respondents could answer several questions, and one can hypothesize that their actions following the identification of fraud would depend on the severity of the fraud and its impacts on both the consumers and the company.

Conclusion

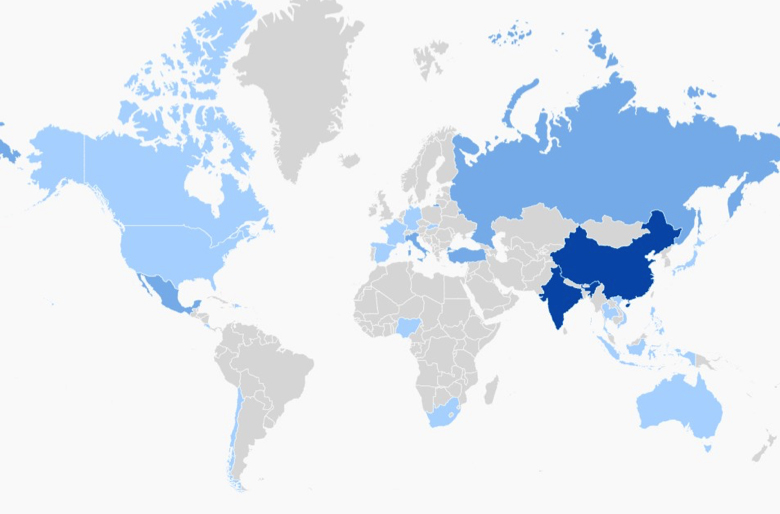

In summary, this survey is the first to assess the knowledge, perception and readiness of FBOs to fight food fraud. Results have indicated that Canadian FBOs understand what food fraud is but data is missing to support their perception that fraud is more present abroad than in Canada. Two third of the respondents feel unsafe towards food fraud which should be seen as positive point; in fact, FBOs would be keener to implement measures to protect themselves if they feel unsafe. Besides, a majority feels responsible for the authenticity of the products they sell to consumers. Respondents tend to implement preventive measures but perceive other measures as more efficient to counter fraud. Apparently, those measures seem to be too expensive, time-consuming and resource-consuming. Besides, lack of training on food fraud management was also reported as an impediment to fight fraud. Finally, differences have been highlighted along the survey between producers and the two others sectors: Processors and distributors. One can hypothesize that producers might feel less concerned by food fraud being at the very beginning of the food chain supply and that most food fraud cases involve their clients and not the producers directly.

Footnotes

- More details and more results are presented in a manuscript submitted by the research team: Food industry perceptions and actions towards food fraud: Insights from a pan Canadian study.

- Researchers involved in the project from the CIRANO: Yoann Guntzburger, Ingrid Peignier and Nathalie de Marcellis-Warin and from the PARERA platform Jeremie Theolier, Virginie Barrere and Samuel Godefroy. Partners: r-Biopharm, EnvironeX, the Quebec consortium for industrial bioprocess research and innovation (CRIBIQ), NSF, Transbiotech, and Olymel.