During the COVID-19 pandemic, the rest of the world has embraced one of the well-known mantras of the food safety profession: Wash your hands, wash your hands, wash your hands. It is equally urgent that we expand that call to arms (or hands) a bit to include: Sanitize your cell phone, sanitize your cell phone, sanitize your cell phone.

A typical cell phone has approximately 25,000 germs per square inch compared to a toilet seat, which has approximately 1200 germs per square inch, a pet bowl with approximately 2100 germs per square inch, a doorknob with 8600 germs per square inch and a check-out screen with approximately 4500 germs per square inch.

Back in the day, when restaurants were still open for a sit-down, dining room meal, during a visit to an upscale Chicago restaurant I had the need to use the restroom. As I left the restroom, an employee, in kitchen whites, walked into the restroom with his cell phone in his hand. It hit me like a bolt of gastrointestinal pain. Even if the employee properly washed his hands, that cell phone with its 25,000 germs per square (and some new fecal material added for good measure) would soon be back in the kitchen. Today, we can add COVID-19 to the long list of potentially dangerous microbes on that cell phone, if the owner of the phone is COVID-19 positive. We also know that the virus can be transferred through the air if someone is COVID-19 positive or has come in close proximity to the surface of a cell phone. As we know, many kitchens are still operating, if only to provide carryout or delivery service. Even though we are not treating COVID-19 as a foodborne illness, great concern remains regarding the transfer of pathogens to the face of the cell phone user, whether it is the owner of the cell phone or someone else who is using it. Just as there are individuals that are asymptomatic carriers of foodborne illness (i.e., Typhoid Mary), we know that there are COVID-19 positive individuals that are either asymptomatic or presenting as a cold or mild flu. These individuals are still highly contagious and the people that may pick-up the virus from them may have a more severe response to the illness.

A recent study from the UK found that 92% of mobile phones had bacterial contamination and one in six had fecal matter. This study was conducted, of course, before the current COVID-19 pandemic. However, consider that the primary form of transfer of the COVID-19 pathogen is from sneezing or coughing. This makes the placement of the virus on the cell phone easier to accomplish than the fecal-oral route because even if the individual recently washed their hands, if they sneeze or cough on their phone, their clean hands are irrelevant.

I also know there is no widely established protocol, for the foodservice industry, food manufacturing industry, sanitizing/cleaning industry, housekeeping, etc., for cleaning and sanitizing a cell phone while on the job. For example, if you examine a dozen foodservice industry standard lists of “when you should wash your hands” you will always see included in the list, “after using the phone”. However, that is usually referring to a wall mounted or desktop land line phone. What about the mobile phone that goes into the food handler’s pocket, loaded with potentially disease-causing germs? I have certainly witnessed a food handler set a cell phone down on a counter, then carefully wash his/her hands at a hand sink, dry their hands and then pick-up their filthy cell phone and either put it in their pocket, make a call or send a text message. What applies to the “food handler” also applies to those individuals on the job cleaning and sanitizing food contact surfaces, and other surfaces that many people will come in direct contact with such as handrails, doorknobs sink handles, and so on.

How can the pathogen count for a cell phone be so high compared to other items you would assume would be loaded with germs? The high number cited for a cell phone is accumulative. How often do you clean your cell phone (or for that matter your keyboard or touch screen)? I’ll bet not very often, if ever. In addition, a frequently used cell phone remains warm and with just a small amount of food debris (even if not visible to the naked eye) creates an ideal breeding environment for bacteria. Unlike bacteria, we know that viruses do not reproduce outside of a cell. The cell phone still presents an excellent staging area for the COVID-19 virus while it waits to be transferred to someone’s face or nose.

While there have been some studies conducted on mobile phone contamination and the food industry, most of the statistics we have come from studies conducted in the healthcare industry involving healthcare workers. If anything, we would hope the hygiene practices in the healthcare environment to be better (or at least as good) as the foodservice industry. It is not a pretty picture. In reviewing various studies, I consistently saw results of the following: 100% contamination of mobile phone surfaces; 94.5% of phones demonstrated evidence of bacterial contamination with different types of bacteria; 82% and so on.

Let’s state the obvious: A mobile phone, contaminated with 1000’s of potentially disease causing germs, acts as a reservoir of pathogens available to be transferred from the surface of the phone to a food contact surface or directly to food and must be considered a viable source of foodborne illness. As we stated earlier, we are not treating COVID-19 as a foodborne illness, but we cannot ignore the role that a cell phone could play in transferring and keeping in play this dangerous pathogen.

What do we do about it? Fortunately we can look to the healthcare industry for some guidance and adapt to the foodservice industry, some of the recommendations that have come from healthcare industry studies.

Some steps would include the following:

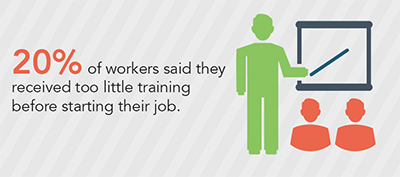

- Education and training to increase awareness about the potential risks associated with mobile phones contaminated with pathogens.

- Establish clear protocols that specifically apply to the use of and presence of mobile phones in the foodservice operation.

- Establish that items, inclusive of mobile phones, that cannot be properly cleaned and sanitized should not be used or present where the contamination of food can occur or …

- If an item, inclusive of a mobile phone, cannot be properly cleaned and sanitized, it must be encased in a “cover” that can be cleaned and sanitized.

- The “user” of the mobile phone must be held accountable for the proper cleaning and sanitizing of the device (or its acceptable cover).

It’s safe to assume the mobile phone is not going to go away. We must make sure that it remains a tool to help us better manage our lives and communication, and does not become a vehicle for the transfer of foodborne illness causing pathogens or COVID-19.