In 1995, a honey processing company was indicted on charges of adulterating industrial honey labeled “USDA Grade A” with corn syrup to increase profits. Ultimately, the jury found in favor of the honey processor, in part because there “weren’t enough regulations governing honey to make the charge stick.”

Honey is defined as “the natural sweet substance produced by honey bees” from the nectar of plants. However, there is not currently an FDA standard of identity for honey in the United States, which would further define and specify the allowed methods of producing, manufacturing and labeling honey (there is, however, a nonbinding guidance document for honey). Some of the details of honey production that a standard of identity might address include allowable timing and levels of supplemental feeding of bees with sugar syrups and the appropriate use of antibiotics for disease treatment.

In circumstances where strict regulatory standards for foods are not available, they may be created by other organizations.

What Is a Food Standard?

A food standard is “a set of criteria that a food must meet if it is to be suitable for human consumption, such as source, composition, appearance, freshness, permissible additives, and maximum bacterial content.”1

To ensure quality, facilitate trade, and reduce fraud, everyone in the supply chain must have a shared expectation of what each food or ingredient should be. Public standards set those expectations and allow them to be shared. They help ensure that stakeholders have a common definition of quality and purity, as well as the test methods and specifications used to demonstrate that quality and purity. Public standards help ensure fair trade, quality and integrity in food supply chains.

How Is a Standard Different from a Method?

A method is generally an analytical technique to assess a particular property of the content or safety of a food or food ingredient. For example, methods for detection of nitrates in meat products or baby food, coliforms in nut products, or high fructose syrups in honey. Methods are an important component of food standards.

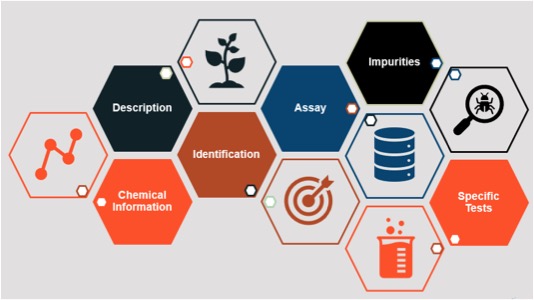

A food standard goes a step further and provides an integrated set of components to define a substance and enable verification of that substance. Standards generally include a description of the substance and its function, one or more identification tests and assays (along with acceptance criteria) to appropriately characterize the substance and ensure its quality, a description of possible impurities and limits for those impurities (if applicable), and other information as needed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Anatomy of an FCC Standard (Source: Food Science Program, Food Chemicals Codex, USP)

A standard defines both what a food or food ingredient should be and documents how to demonstrate compliance with that definition.

Public Standards and Food Fraud Prevention

Many of the foods prone to fraud are those that are not simple food ingredients, but agricultural products that can be more complex to characterize and identify (such as honey, extra virgin olive oil, spices, etc.). Milk products are an example of a commodity that is prone to fraud with a wide range of adulterants (for example, fluid cow’s milk is associated with 155 adulterants in the Food Fraud Database). Ensuring the quality and purity of a product link milk requires implementation of multiple analytical techniques or the development of non-targeted methods.

The creation of effective public standards with input by a range of stakeholders will be particularly important for ensuring the quality, safety and accurate labeling of these high value commodities in the future.

Reference

- A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition 2005, Oxford University Press.

Resources

- The Food Chemicals Codex is a source of public standards for foods and food ingredients. It was created by the U.S. FDA and the National Institute of Medicine in 1966 and is currently published by the nonprofit organization USP. The FCC contains 1250 standards for food ingredients, which are developed by expert volunteers and posted for public comment before publication.

- The Decernis Food Fraud Database is a continuously updated collection of food fraud records curated specifically to support vulnerability assessments. Information is gathered from global sources and is searchable by ingredient, adulterant, country, and hazard classification. Decernis also partners with standards bodies to provide information about fraudulent adulterants to support standards development.