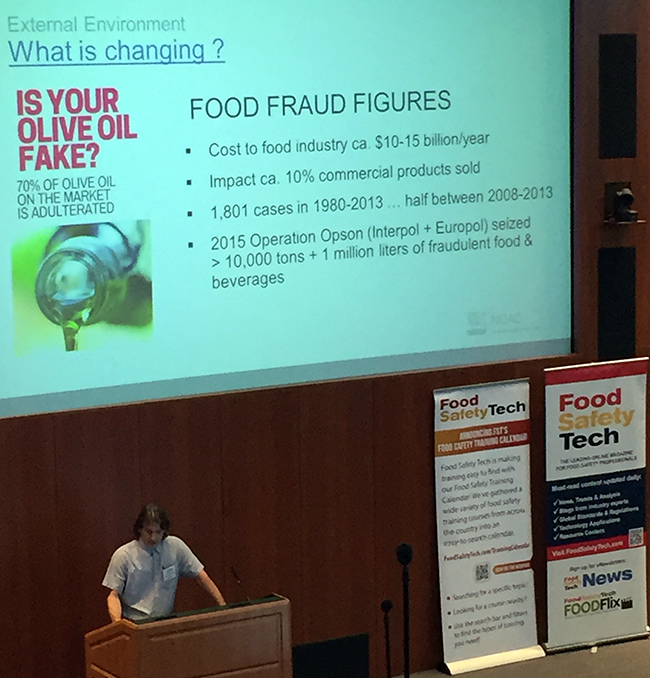

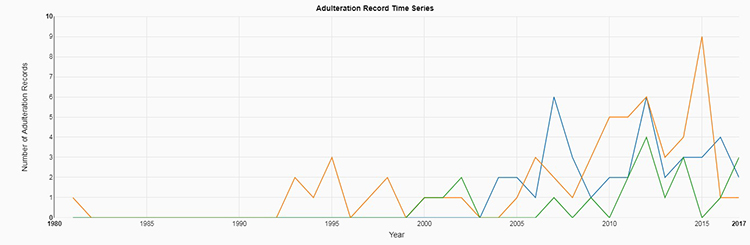

You would be forgiven for thinking that food fraud is a sporadic issue but, with an estimated annual industry cost of $50 billion dollars, it is one currently plaguing the food and drink sector. In the UK alone, the food and drink industry could be losing up to £12 billion annually to fraud.

As the scale of food fraud becomes more and more apparent, a heightened sensitivity and awareness of the problem is leading to an increasing number of cases being uncovered.

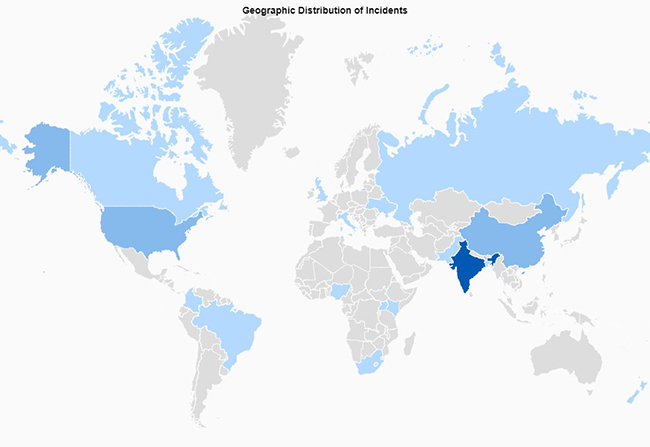

Recently: Nine people contracted dangerous Vibrio infections in Maryland due to mislabeled crabmeat from Venezuela; food fraud raids have been conducted in Spain over fears of expired jamon re-entering the market; and authorities seize 1 ton of adulterated tea dust in India.

Spurred by the complexity of today’s global supply chains, food fraud continues to flourish; attractive commercial incentives, ineffective regulation and comparatively small penal repercussions all positively skew the risk-reward ratio in favor of those looking to make an extra dollar or two.

The 2013 horsemeat scandal in Europe was one such example, garnering significant media attention and public scrutiny. And, with consumers growing more astute, there is now more onus on brands to verify the origin of their products and ensure the integrity of their supply chains.

Forensic science is a key tool in this quest for certainty, with tests on the product itself proving the only truly reliable way of confirming its origin and rooting out malpractice.

Current traceability measures—additives, packaging, certification, user input—can fall short of this: Trace elements and isotopes are naturally occurring within the product and offer a reliable alternative.

Chemical Fingerprinting for Food Provenance

Like measuring the attributes of ridgelines on the skin of our fingertips as a unique personal identifier, chemical fingerprinting relies on differences in the geochemistry of the environment to determine the geographic origin of a product—most commonly measured in light-stable isotopes (carbon, nitrogen, sulphur, oxygen, hydrogen) and trace elements.

Which parameters to use (either isotopes, TEs or both) depends very much on the product and the resolution of provenance required (i.e. country, farm, factory): Isotope values vary more so across larger geographies (i.e., between continents), compared to smaller scales with TEs, and are less susceptible to change from processing further down the supply chain (i.e., minced beef).

The degree of uptake of both TEs and light isotopes in a particular produce depends on the environment, but to differing extents:

TEs are related to the underlying geochemistry of the local soil and water sources. The exact biological update of particular elements differs between agricultural commodities; some are present with a lot of elements that are quantifiable (“data rich” products) while others do not. We measure the presence and ratio of these elements with Inductively Coupled Plasma—Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) instrumentation.

Light Isotopes are measured as an abundance ratio between two different isotopes of the same element—again, impacted by environmental conditions.

Carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) elements are generally related to the inputs to a given product. For example, grass-fed versus grain-fed beef will have a differing C ratio based on the sugar input from either grass or grain, whereas conventionally farmed horticulture products will have an N ratio related to the synthetic fertilisers used compared to organically grown produce.

Oxygen (O) and hydrogen (H) are strongly tied to climatic conditions and follow patterns relating to prevailing weather systems and latitude. For ocean evaporation to form clouds, the O/H isotopes in water are partitioned so that droplets are “lighter” than the parent water source (the ocean). As this partitioning occurs, some droplets are invariably “lighter” than others. Then, when rainfall occurs, the “heavier” water will condense and fall to the ground first and so, as a weather front moves across a landmass, the rainfall coming from it will be progressively “lighter”. The O/H ratio is then reflected in rainfall-grown horticultural products and tap water, etc. Irrigated crops (particularly those fed from irrigation storage ponds) display different results due to the evaporation, which may occur over a water storage period.

Sulphur (S) has several sources (including anthropogenic) but is often related to distance from the sea (“the sea spray effect”).

Analysis of light isotopes is undertaken with specialist equipment (Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry, IRMS), with a variety of methods, depending on product and fraction of complex mixtures.

Regardless of the chemical parameter used, a fingerprinting test-and-audit approach requires a suitable reference database and a set of decision limits in order to determine the provenance of a product. The generation of sample libraries large enough to reference against is generally considered too cost prohibitive and so climatic models have been developed to establish a correlation between observed weather and predicted O/H values. However, this approach has two major limitations:

- The chemical parameters related to climate are restricted (to O and H) limiting resolving power

- Any model correlation brings error into further testing, as there is almost never 100% correlation between measured and observed values.

As such, there is often still a heavy reliance on building suitable physical libraries to create a database that is statistically robust and comprehensive in available data.

To be able to read this data and establish decision limits that relate to origin (i.e., is this sample a pass or fail?), the parameters that are most heavily linked to origin need to be interpreted, using the statistics that provide the highest level of certainty.

One set of QC/diagnostic algorithms that use a number of statistical models have been developed to check and evaluate data. A tested sample will have its chemical fingerprint checked against the specific origin it is claimed to be (e.g, a country, region or farm), with a result provided as either “consistent” or “inconsistent” with this claim.

Auditing with Chemical Fingerprints

Chemical fingerprinting methods do not replace traditional traceability systems, which track a product’s journey throughout the supply chain: They are used alongside them to confirm the authenticity of products and ensure the product has not been adulterated, substituted or blended during that journey.

A product can be taken at any point in the supply chain or in-market and compared, using chemical fingerprinting, to the reference database. This enables brands to check the integrity of their supply chain, reducing the risk of counterfeit and fraud, and, in turn, reducing the chance of brand damage and forced product recalls.

Click on page 2 below Related Content to continue reading this article