A culture of food safety is built on a set of shared assumptions, behaviors and values that organizations and their employees embrace to produce and provide safe food. Employees must know the risks and hazards associated with their specific products, and know why managing these hazards and risks in a proactive and effective manner is important. In an organization with a strong food safety culture, individuals and peers behave in a way that represents these shared assumptions and value systems, and point out where leaders, peers, inspectors, visitors and others may fail to protect the safety of both the consumers and their organizations.

A number of factors influence these organizations, such as changing consumer demographics, emerging manufacturing hazards, and the regulatory environment. The United Nations predicts that the number of people over 60 years will double by 2035, the number of diabetes patients will increase by 35% (International Diabetes Federation), and the number of individuals living with dementia will increase by 69% (Alzheimer’s Disease International). This poses an increased urgency for food manufacturers, as these population cohorts are more susceptible to foodborne infections or may have challenges with food preparation instructions.

Much has been published on food safety culture, and we owe it to the front-runners to use their work to go deep into practical, everyday challenges and to continuously strengthen organizational and food safety culture.1 An element common to most of these publications is a reference to the importance of behaviors.2-8

There is a renewed recognition of the importance of individual behaviors specific to food safety and personal self-discipline in food processing and manufacturing organizations. Employees throughout the organization must be aware of their role and the expected food safety behaviors, and held accountable for practicing these behaviors. Embedding food safety culture in an organization can be very challenging given the need to carefully define appropriate behaviors, the difficulty in changing learned behaviors, and the complexity of objectively evaluating the level of food safety culture in a company. This article is an attempt to define useful food safety behaviors and to describe a behavior-based method that you can use to measure the maturity of your organization’s food safety culture.

Defining measurable behaviors

Behaviors is the element that, when combined with results, creates performance.9 Behaviors, if used to measure and strengthen food safety culture, must be defined carefully in a consistent, specific, and observable manner. Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen, authors of multiple publications on the Reasoned Action Approach, teach us how these three factors can be used to predict and explain human behavior, attitude, perceived norms and perceived control.10 They also teach us that behaviors can be defined consistently by including four elements (Figure 1).

Case: CCP operator on a baked chicken line. I work in a chicken processing company and am responsible for monitoring the internal cook temperature of chicken breasts after the product has gone through the oven. One of the important behaviors for my role could be defined as “Measure temperature of chicken after oven at predetermined time intervals”. This behavior is consistent, as it includes all four elements of the behavior definition (Table 1). The content of the behavior is defined in a way that makes it relevant for me, the CCP operator, and I am clear on the assumptions made by others on the processing line about my behavior. The behavior is observable and most people would be able to enter the processing area, observe the behavior and assess if it is performed as needed, YES or NO.

Leaving out any of the four elements of a behavior definition or becoming too general in your statements leads to poorly defined behaviors that are difficult to use as an assessment of behaviors, and ultimately as a measure of the sites for food safety culture (Table 1).

| Scenario | Behavior | Action | Context | Target | Timing |

| Consistent, relevant, and observable | Measure and record temperature of three chicken pieces every hour at end of oven | Measure and record temperature | End of oven | Three chicken pieces | Every hour |

| Missing definition elements | Measure temperature at pre-determined intervals | Measure temperature | Not defined | Not defined | Pre-determined time intervals |

| Not specific | The product is cooked and checked every hour | Not defined | Not defined | The product | Every hour |

| Not observable | The product is cooked and check to see if it meets standard | Checked | Not defined | The product | Not defined |

| Table 1: Scenarios of defining behaviors | |||||

Behaviors are observable events and for this to be true, a behavior must be defined objectively in a language clear to everyone involved. It can be helpful to target a grade-six readability level, as it forces everybody writing the behavior to avoid words that are not understood in plain language.

Using behaviors to measure food safety culture

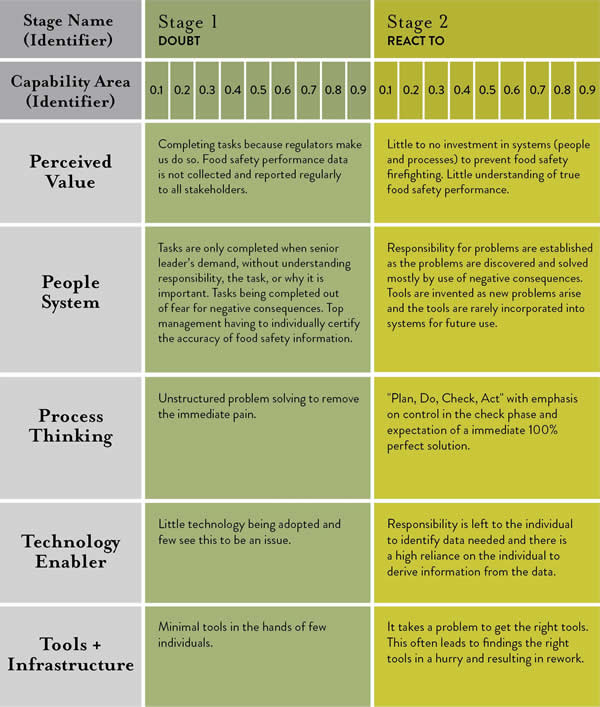

Assuming that behaviors are defined in a consistent, specific, and observable format, how do we decide the critical few behaviors that get measured? A suggested method is the use of the food safety maturity model (Table 2). The model outlines five capability areas that a processor or manufacturing company can use to measure its current state and to set priorities and direction. One capability area is Perceived Value that describes how an organization might see the value of food safety. The maturity level ranges from a low level of maturity of “Checking the box because regulators make us” to a high level of maturity for “food safety is an enabler for ongoing business growth and improvement”. Consistent, specific, and observable behaviors can be defined for each of these stages of maturity. By assessing the performance of these behaviors we can aggregate these assessment scores into a site or organization measure of the maturity of the site or organizational food safety culture. It is important to note that the maturity score does not measure “good or bad” culture. The measure is one of progression along the food safety maturity model scale, and can therefore be used to highlight areas of strength and help prioritize areas of improvement for the individual organization.

|

|

| Table 2: Food Safety Maturity Model. The Food Safety Maturity Model was developed by Lone Jespersen in collaboration with Dr. John Butts, Raul Fajardo, Martha Gonzalez, Holly Mockus, Sara Mortimore, Dr. Payton Pruett, John Weisgerber, Dr. Mansel Griffiths, Dr. Tanya Maclaurin, Dr. Ben Chapman, Dr. Carol Wallace, and Deirdre Conway. For more details on the food safety maturity model, visit www.cultivatefoodsafety.com. |

|

Call to Action

The organization’s culture will influence how individuals throughout the group think about safety, their attitudes towards safety, their willingness to openly discuss safety concerns and share differing opinions with peers and supervisors, and, in general, the emphasis that they place on safety. However, to successfully create, strengthen, or sustain a food safety culture within an organization, the leaders must truly own it and promote it throughout the organization.8

The call-to-action for food industry leaders and regulators is to embrace a standardized measure of food safety culture to allow for comparison and sharing within an organization and between companies. “Food safety is everybody’s responsibility” was the theme of the recent GFSI Global Food Safety Conference in Kuala Lumpur, but to act on this with food safety culture as the ultimate outcome, we must adopt standardized measure. The GFSI benchmarking technical working group is an ideal forum to continue this dialogue.

During the upcoming GMA Science Forum April 12-15, 2015 join the conversation at a practical and detailed level. The preconference Food Safety Culture workshop takes place April 12, with facilitators from leading organizations; the Food Safety Culture Signature Session on April 13 will discuss what our industry requires to enable this level of standardization and collaboration. For more information and to sign-up, visit http://www.gmaonline.org/forms/meeting/Microsite/scienceforum15.

References

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ball, B., Wilcock, A., & Aung, M. (2009). Factors influencing workers to follow food safety management systems in meat plants in Ontario, Canada. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 19(3), 201-218. doi:10.1080/09603120802527646.

- Hanacek, A. (2010). SCIENCE + CULTURE = SAFETY. National Provisioner, 224(4), 20-22,24,26,28-31.

- Hinsz, V. B., Nickell, G. S., & Park, E. S. (2007). The role of work habits in the motivation of food safety behaviors. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 13(2), 105-114. doi:10.1037/1076-898X.13.2.105.

- Nickell, G. S., & Hinsz, V. B. (2011). Having a conscientious personality helps an organizational climate of food safety predict food safety behavior. Food Supplies and Food Safety,189-198.

- Jespersen, L., & Huffman, R. (2014). Building food safety into the company culture: A look at maple leaf foods. Perspectives in Public Health, (May 8, 2014) doi:DOI: 10.1177/1757913914532620.

- Seward, S. (2012). Assessing the food safety culture of a manufacturing facility. Food Technology, 66(1), 44.

- Yiannas, F. (2009). In Frank Yiannas. (Ed.), Food safety culture creating a behavior-based food safety management system. New York: Springer, c2009.

- Braksick, L. W. (2007). Unlock behavior, unleash profits (Second ed.) McGraw-Hill.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2009). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. London, GBR: Psychology Press.