With an ever-expanding international food trade and new government demands for food safety and supply chain transparency, the U.S. regulatory landscape is becoming increasingly more complex. FSMA (especially the Foreign Supplier Verification Program) aims to shift responsibilities for imported food safety from FDA to importers in an effort to reduce the regulatory burden on FDA. New regulations bring new burdens to food trade stakeholders, requiring significant investment. However, many of the data obligations of the FSVP rule dovetail with other agencies’ requirements.

Investments in one dataset can be leveraged to improve a company’s overall compliance related to international trade. The key is to integrate FSVP requirements into a strong regulatory compliance program without breaking the bank. This requires identifying data overlap, utilizing compliance integration to work smarter, not harder, leveraging the window of opportunity to collect more (and necessary) data from your foreign suppliers, and calling in the right help when needed.

TRUST…..BUT VERIFY: 2018 FSMA Focuses on Supplier Verification Activities | Learn more at the Food Safety Supply Chain Conference | June 12–13, 2018 | Rockville, MDToday’s International Supply Web

No longer can we reasonably talk about establishing, monitoring and maintaining a supply “chain” when importing anything. International trade in food and its ingredients is rarely bilateral—except for perhaps fresh produce, meat and seafood. Instead, food moves throughout a complex supply web of international transactions. Most processed food now contains ingredients from multiple countries, leading to food safety verification challenges and country of origin questions for finished goods.

The international supply web includes farms (land and aquaculture), agriculture cooperatives, food grade chemicals manufacturers, color and flavoring formulators and manufacturers, raw materials processors and fabricators, finished food processors & packers, warehouses, transportation companies, cooking, canning and irradiating facilities, shippers, exporters, product and commodities brokers, importers, wholesalers, retailers and e-tailers. Any (or all) of these players may be small operations located in different countries or multi-national conglomerates operating on several continents. There is very little food consumed in the United States that is not affected, in some way or another, by international commerce and trade.

Shift to a Preventive System

In 2011, Congress passed FSMA with the goal of moving U.S. food safety from a reactive to a preventive system, and integrating HACCP-like principles into the production of all food. Over the ensuing years, FDA issued seven major regulations that address various facets of food safety.

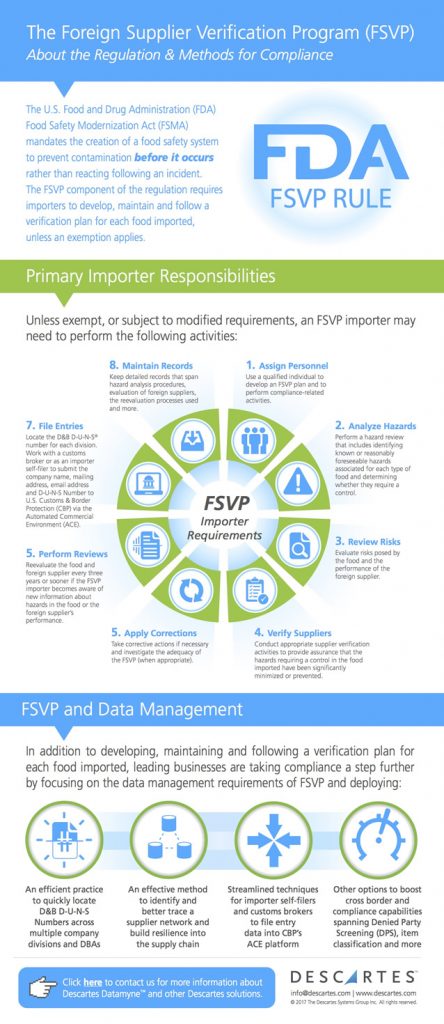

The Foreign Supplier Verification Program (FSVP) rule was included as a way to ensure that foods imported into the United States are produced in a manner that meets U.S. safety standards. FSVP requires that “importers,” which can be the distributors or retailers of products, verify and document the steps taken to ensure safe production of animal and human food. While the exact FSVP requirements vary depending on the commodity, the FSVP process often includes developing, maintaining and documenting a food safety plan and, as its name suggests, verifying that foreign suppliers are controlling for appropriate hazards. Developing and implementing these plans requires a wide variety of skills, including hazard analysis and risk assessment, establishing preventive controls, developing recall plans, and careful documentation of the process. FSVP also requires that verification activities be carried out by parties who have specific preventive control training, or “PCQIs” (Preventive Control Qualified Individuals).

Most importantly, FSMA and the FSVP rule shift the burden of safety from FDA to the importer. With increased interconnectedness, flaws in food safety documentation can become magnified throughout the system. Note that FSVP covers food safety only—not necessarily food traceability or food security defense—although there are opportunities for crossover ROIs. To achieve FSVP compliance, you need to know who is handling your food before it is imported, what they know about food safety, and how they apply food safety principles.

Cross-agency Data Usage

Approaching FSVP as a stand-alone regulatory compliance initiative is expensive and inefficient. Many activities and data elements that must be kept for other government agencies and their compliance programs should be linked together. The data your foreign suppliers must provide to international carriers for advanced notice to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (“CBP” or “Customs”) by importing carriers (airlines, trucking companies and vessel operators) is relevant to both Customs entry and FDA food safety compliance and documentation. This overlap presents an ideal opportunity to relieve the burden of the new FSVP requirements and kill two birds with one stone. And the overlap and leveraging opportunities are actually quite substantial—if one knows where and how to look for them.

For example, the USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP) regulations specify requirements for the processing, handling and labeling of raw materials and processed goods to meet organic standards. Organic labeling and marketing claims are affirmative assertions that the labeled food has not been exposed to processing steps, processing chemicals or particular substances (e.g., sewage sludge, ionizing radiation) that would cause it to fall out of the regulatory bounds of an organic food product. Where organic processing and handling crosses over to food safety, leveraging organic compliance documentation buttresses the safety of the resulting food—and the importer’s FSVP program.

Additionally, much of the information that the importer must know to properly classify their product under the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) is the same information that the importer needs for their FSVP plan; the importer must know the products, what they are made from, how they are processed, and how they are intended to be used to both properly classify and verify the safety of their product. Because FDA requires the importer to verify that its foreign supplier has a system that meets the domestic food safety standards, the foreign supplier must also be able to identify its own ingredient and raw material suppliers and their systems for food safety, as applicable. Therefore, the food importer’s FSVP process promotes documentation compliance with CBP’s and other government agencies’ requirements governing the country of origin of materials for applicability of preferential duty rates (e.g., under a free trade agreement) and country of origin labeling.

Another example of data overlap is the FSVP requirement for supplier verification and the responsibility to show correct valuation of your product for Customs. FSVP requires that you verify your suppliers and ensure your product is genuine, and Customs requires that you declare an appropriate valuation and identity for your shipment. If Customs investigates your shipment and determines your valuation is incorrect, it may trigger the Department of Commerce to investigate whether there are anti-dumping and countervailing issues going on with the product.

Issues with anti-dumping and countervailing duties are extremely time-consuming and expensive. In both 2008 and 2016, federal authorities investigated rumors of companies circumventing anti-dumping duties by transshipping food products through third countries (to conceal actual origin of the material). When Customs investigated a honey processing plant, they found evidence that the purported processor of Vietnamese honey was receiving finished product from China and relabeling it as originating from Vietnam. When importers declared imported Vietnamese honey, Customs determined from trace mineral testing that the honey was, as they suspected, Chinese. Customs seized the product. The lesson to learn from this is to know your suppliers and the actual supply web. In the case of country of origin violations, not verifying the country of origin can be costly. Where CBP finds negligence is involved, the agency can look back five years to recoup lost duty plus interest, and can even reopen old liquidated entries and assess monetary penalties. In completing your FSVP plan, requesting documentation demonstrating origin is a small additional step that furthers the strength of CBP-required documentation to support the origin declaration at entry. That’s leveraging.

Document, Document, Document

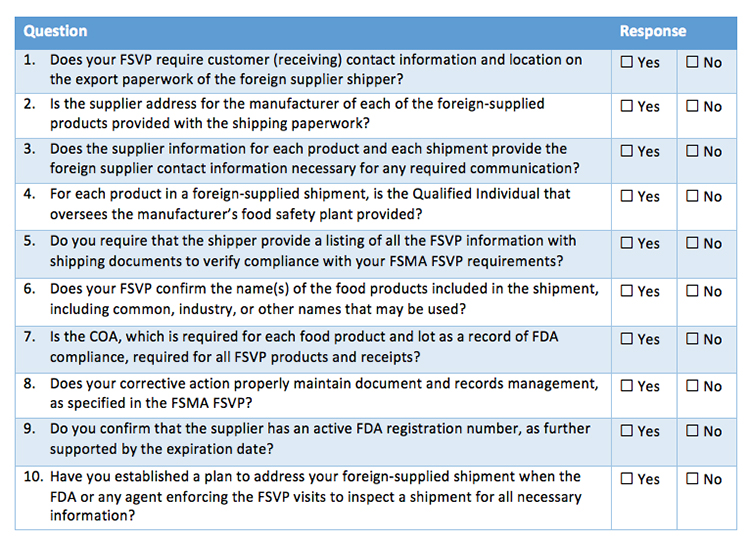

Under the Customs Modernization Act of 1993, the compliance watch-words for all importers (and customshouse brokers) are “record keeping,” “shared responsibility,” “reporting,” and “due diligence.” Anything that is required for a proper importation is subject to CBP review and audit—whether the requirement arises as supply chain and source data under the Seafood Import Monitoring Program (SIMP) under the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), or organic labeling and compliance under USDA’s NOP regulations, or speciation documentation under the Lacey Act enforced by U.S. Fish and Wildlife (USFW), or FSVP implemented by FDA. Therefore, the engagement between food importer and foreign food supplier forced by FSVP opens the opportunity for the importer to clarify and shore up its documentation obligations for many other coexisting regulatory regimes.

A clear demonstration of this fact is borne out by the regular process that ensues when CBP issues to an importer of record a Customs Form 28 (or “CF28”). The CF28 is a CBP request for additional information relating to an imported shipment. The importer is usually required to respond within 30 days of its issuance. But ordinarily the CF28 is issued months (and sometimes years) after the importation occurred. Therefore, the CF28 process represents a significant challenge to the importer’s record keeping and compliance documentation systems, and legal liability to the importer’s bottom line.

Documents needed to respond adequately to a CF28 include contracts, purchase orders, packing lists, shipping documents, declarations to government authorities throughout the import process, powers of attorney, country of origin certifications, emails and other communications discussing any of these documents. CBP requests these documents to confirm the proper electronic data was submitted with the importation. And, of course, CBP is checking to see if the importer is attempting to circumvent U.S. import or export laws that may deprive the government of revenue.

The identity and location of an importer’s trading partners (including the foreign supplier and its suppliers), contracts between and among them (e.g., related to description, processing methods, equipment used, quality and condition of goods), origin documentation, proofs of packing and shipping, etc., are all subject to production via the CF28 process. Penalties for errors in the documentation that result in a regulatory or administrative action are imposed upon the importer (for failing to document or exercise due diligence in performing its function as an importer under U.S. law).

The FSVP regulation presents an ideal opportunity for the importer to establish and populate a compliance program that integrates its FDA import regulatory obligations with those of CBP and other regulatory agencies, as applicable. Failing to take this rare opportunity—at a time when foreign suppliers are expecting probing questions from their U.S. trading partners—is a mistake.

Because the government is more connected, it is essential to change how you prepare for and respond to issues that arise. Just as the FDA’s FSVP rule aims to move food safety from a reactionary to preventive system, coordinated proactive compliance with all government agency requirements will be necessary for the future. Further, with new regulations, your customs broker may not be equipped to deal with certain areas or when administrative matters escalate. But how do you prepare for any eventuality when the enforcement possibilities seem endless?

When preparing your FSVP plans, reviewing your Customs documentation, and reviewing other government agency requirements, it is critical that you think through all the potential issues that may arise with your product or its supply chain, and address them proactively in your documentation. What might an inspector or compliance officer think about the information provided? Is it thorough, clear, and logical? Does it tell a consistent narrative? What if another agency sees this information? Will they have further questions? The ultimate goal is accurate and thorough data for submissions to FDA, Customs and any other partner government agencies.

Key Steps to Prepare for the Worst-case Scenario

Lastly, let’s not forget that part of being prepared is preparing for the worst-case scenario. What happens when you are confronted by an issue? We recommend taking four key steps. First, marshal your resources (documents, documents). Second, ask, “Who are the key players in the story (e.g., which agencies are involved or could possibly be involved, and what are they requesting)?” The third question, a bit less straightforward, is, “How must I respond? (e.g., is the agency within its regulatory authority and required time constraints; are there conflicts of interest; what is the potential legal exposure to risk for different actions)?” Finally, do a gut check: Are the examinations subjective in nature or qualitative (rather than quantitative)? Is any required testing appropriate for the product? If you feel you cannot confidently answer these questions using current staff, we recommend you prepare for import issues by selecting professionals who have experience with integrated agency regulations and legal compliance requirements. The keys to expediting the process when working with multiple government regulatory agencies are integrating your compliance to ensure you have a true green-means-go light before you ship and being able to present a clear and consistent regulatory narrative to all agencies. This requires a clear understanding of how the government regulatory requirements actually intersect.