The unlimited supply of food sources that manufacturing facilities provide can make pest management a daunting task, especially with the scrutiny of third-party auditors, government regulators and customers. These high standards, along with yours, mean that diligence is a key ingredient in the recipe for pest management success.

Why is this important? The steps you take to prevent pests, and how issues are resolved if pest activity is detected, affects the overall credibility of your business. After all, pest management can account for up to 20% of an audit score.

Auditors look for an integrated pest management (IPM) plan, which includes prevention, monitoring, trend reports and corrective actions. If you want to stay audit-ready, all the time, implement the following five principles.

Open Lines of Communication

A successful pest management partnership is just that: A partnership. Create an open dialogue for ongoing communication with your pest management provider. Everyone has a role to play from sanitation to inspection to maintenance. For example, if there are any changes in your facility, such as alteration of a production line, let your provider know during their next service visit. During each visit, it’s important to set aside time to discuss what was found and done during the visit, including new pest sightings and concerns.

Communication shouldn’t be limited to the management team; your entire staff should be on board. During their day-to-day duties, employees should know what to look for, and most importantly, what to do if they notice pests or signs of pests. Reporting the issue right away can make a huge difference in solving a pest problem before it gets out of hand. Also, most pest management providers offer staff training sessions. These can be an overview of the basics during your next staff meeting or a specialized training on a pertinent issue.

Inspect Regularly

A thorough inspection can tell you a lot about your facility and the places most at risk for pests. Your pest management provider will be doing inspections every visit, but routine inspections should be done by site personnel as well. Everyone at the site has a set of eyes, so why not use them? This way, you can identify hot spots for pests and keep a closer eye on them. Pests are small and can get in through the tiniest of gaps, so some potential entry points to look out for are:

• Windows and doors. Leaving them propped open is an invitation for all sorts of pests. Don’t forget to check the bottom door seal and ensure it is sealed tight to the ground.

- Floor drains. Sewers can serve as a freeway system for cockroaches, and drains can grant them food, water and shelter.

- Dock plates. A great entry point for pests, as there are often gaps surrounding dock plates.

- Ventilation intakes. These are a favorite spot for perching, roosting or nesting birds, as well as entry points for flying insects.

- Roof. You can’t forget about the roof, as it serves as a common entry point for birds, rodents and other pests.

Another thing to look for is conducive conditions, such as sanitation issues and moisture problems. These are areas where there may not be pests yet, but they provide a perfect situation that pests could take advantage of if they aren’t dealt with. Make sure to take pictures of deficiencies so that can be shared with the maintenance department or third-party who can fix it. You can also take a picture of the work when it has been finished, showing the corrective action!

Keep It Clean

Proper sanitation is key to maintaining food safety and for preventing and reducing pests. You need a written sanitation plan to keep your cleaning routine organized and ensure no spots are left unattended for too long. The following are some additional steps consider:

- Minimize and contain production waste. While it’s impossible to clean up all the food in a food processing site (you are producing said food!), it’s important to clean up spills quickly and regularly remove food waste.

- Keep storage areas dry and organized.

- Remember FIFO procedures (first in, first out) when it comes to raw ingredients and finished products.

- Clean and maintain employee areas such as break rooms and locker rooms.

- Ensure the outside of your facility stays clean and neat with all garbage going into trash cans with fitted lids.

- Make sure dumpsters are emptied regularly and the area around them kept clean.

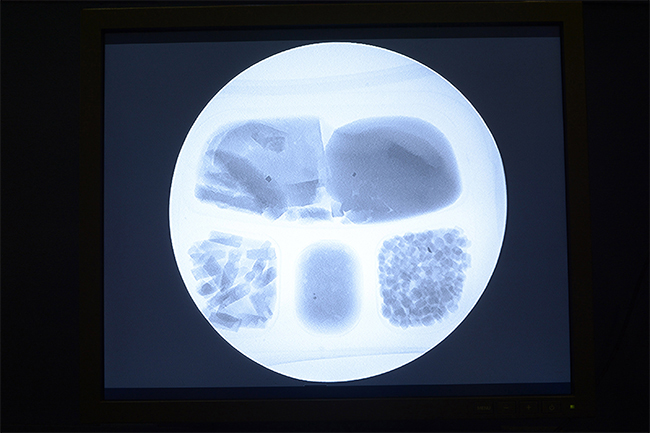

Monitoring

Monitoring devices for many pests will be placed strategically around your facility. Some common ones are insect light traps (ILTs), rodent traps and bait stations, insect pheromone traps and glue boards. It’s important to let employees know what these are there for and to respect the devices (try not to run them over with a fork lift or unplug them to charge a cell phone). These devices will be checked on a regular basis and the type of pest and the number of pests will be recorded. This data can then be analyzed over time to show trends, hot spots, and even seasonal issues. Review this with your pest management provider on a regular basis and establish thresholds and corrective actions to deal with the issues when they reach your threshold. The pest sighting log can also be considered a monitoring tool. Every time someone writes down an issue they have seen, this can be quickly checked and dealt with.

Maintain Proper Documentation

Pest management isn’t a one-time thing but a cycle of ongoing actions and reactions. Capturing the process is extremely important for many reasons. It allows you to analyze, refine and re-adjust for the best results. It’s a great way to identify issues early. Also, it’s a critical step for auditors. Appropriate documentation must be kept on hand and up-to-date. There’s lots of documentation to keep when it comes to pest management and your provider should be keeping all of that ready—from general documentation like your annual facility assessment and risk assessment to training and certification records, pest sighting reports, safety data sheets and more.

The documentation aspect may seem like a lot at first, but a pest management provider can break it down and make it easier. It’s absolutely necessary for food and product safety and will become second nature over time.