In vitro diagnostics provider bioMérieux recently announced its plans to open a new, 32,000 sq. ft. state-of-the-art molecular innovation center at the Navy Yard in Philadelphia. The new site will house the company’s xPRO Program, as well as the company’s Predictive Diagnostics Innovation Center.

The xPRO Program was created to speed development of advanced molecular diagnostics for food quality and safety departments in the food and beverage, nutraceutical and cannabis indsutries.

We spoke with Ben Pascal, head of xPRO at bioMérieux, about the program as well as the challenges and recent advances in the development of molecular assays and predictive diagnostics.

What is the xPro program?

Pascal: xPRO is an entrepreneurial engine for bioMérieux. We have had tremendous success with the molecular assays we’ve built over the years here, and we want to continue to invest in that innovation both in terms of the way we develop these assays, the speed with which we bring them to market, and we want to expand the partnerships that we’ve built with industry. All of these efforts are bolstered through the xPRO program and team.

What are some of the challenges in developing the molecular assays?

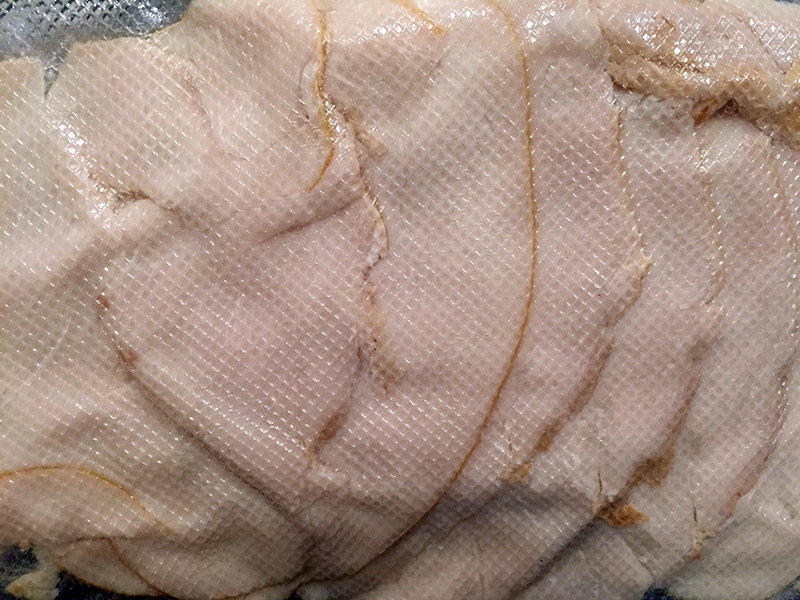

Pascal: In the clinical micro sector, you’ve got blood, saliva, and urine, and they are pretty uniform between everyone. When you come to the industrial micro sector, where you’re working with lettuce one day, ground beef the next and then nutraceuticals or spices, it is far more challenging to build a diagnostic that can work across all those matrices.

The challenge is how to create something that is compatible in multiple sectors, is faster and will deliver value over and over in a routine quality testing lab. Experience is crucial. Our team in Philadelphia has built and commercialized more than 30 molecular diagnostics, so we had the opportunity to put together a toolkit, if you will, to help us get through challenging matrices and speed things along with regards to recovery of target organisms.

When you talk about predictive diagnostics, is this related to gaining a better understanding of which pathogens are most likely to cause illness and at what levels?

Pascal: You do have these pathogens, but there’s a whole other concern related to spoilage. Day to day in the food and beverage sector, it’s spoilage that’s affecting quality and your brand reputation and causing recalls.

When it comes to pathogens that can cause foodborne illnesses, one cell is typically the law of the land. But when we say predictive diagnostics, we are isolating unique genes that are 100% predictive of spoilage. We know there are certain organisms that cause spoilage, but not all organisms that spoil are created equal. So what we try to tease out through our genomic and predictive diagnostic center is which unique genes allow one bug within the same species to cause spoilage, while another does not.

Traditionally, a quality director on the floor will say, I have this organism. It might spoil it might not. We’re taking the risk out of the equation. If you have a potential spoilage organism and you know that it has the specific genes that create spoilage, you can make more informed decisions on what you’re going to do with your product in terms of releasing it or remediating it.

For example, in brewing there is a yeast called saccharomyces cerevisiae that is often used. And there is a variant of saccharomyces cerevisiae that has some genes that allow it to use up residual starches in the product to produce gas, which causes the cans to swell and burst.

The problem is, you can’t tell from a culture plate whether your saccharomyces cerevisiae has this variant diastaticus or not—and not all diastaticus will go on to chew up those residual starches as an energy source and produce gas. We’ve identified a unique set of genes, and every time those genes are there, that diastaticus will go on to produce gas and create quality issues. That’s what we refer to as predictive diagnostics.

When you talk about rapid diagnostic testing, can these tests be performed in the food or beverage facility?

Pascal: Yes, they take our equipment and utilize it at their site, whether that be a third party laboratory, the production site of a brewery, a food processing facility or a nutraceutical manufacturer. We manufacture the equipment and the reagents that we’ve developed, and we put that into a test kit that customers can purchase after we’ve installed the equipment at their production site.

Are there any specific food areas that you’re focusing on now?

Pascal: Some of our key focuses relate to beverages, both alcoholic and non-alcoholic. We do quite a lot in nutraceuticals. We do quite a bit of work in cannabis, and in food safety, we’re focused on changing the game with regards to environmental monitoring. With environmental monitoring you’re looking for specific pathogens with the theory being, if you can control your environment, you can control what gets into your food products.

You’re typically looking for one of two pathogens: salmonella or listeria. We said, why not do them both together? And we created a universal medium. By providing specific data points for both pathogens within a single test, it can detect and enrich both salmonella and listeria from the environmental swab.

In all the work we do, our partnerships with industry are very important. The way that we build our pipeline is directly through partnerships with industry, which informs us on their key challenges as well as better ways to make tools. So, when we come out with a new tool, our goal is to not only meet the needs of our partner but meet or exceed the needs of their peers in the industry as well.