Burgers are the quintessential American food. But as prices continue to rise in the beef industry and U.S. consumers seek more health-conscious alternatives such as veggie and salmon burgers, some food companies may be cutting corners. Clear Labs used next-generation genomic sequencing (NGS) to conduct molecular analysis of 258 burger products (ground meat, frozen patties, fast food burgers and veggie burger products from 79 brands and 22 retailers) and found significant issues—instances of substitution, missing ingredients, pathogens or hygienic problems—in about 14% of samples. This is a red flag for industry, indicating a need to remain vigilant about vulnerabilities in the supply chain and the way in which products are tested.

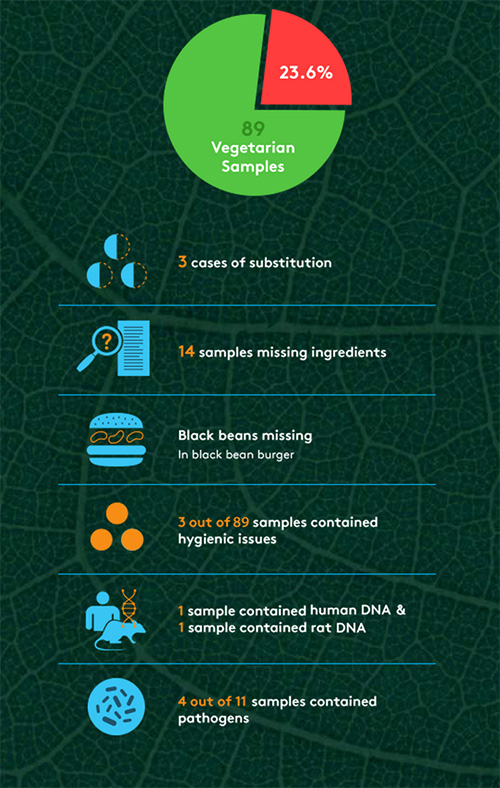

Ironically, perhaps the biggest problems that The Hamburger Report revealed surrounded meat-alternative products. Out of 89 vegetarian samples, 23.6% were found to have issues, from ingredient substitutions to rat DNA to pathogens (see Figure 1). “We were surprised by the higher rate of problems in veggie burgers,” says Mahni Ghorashi, co-founder of Clear Labs. “There were nearly twice as many problems in those samples as their meat counterparts, which is surprising, because you normally think of a veggie product as perhaps a safer bet, but we actually found more cases of pathogen strains. And we found things like beef in veggie products, which isn’t acceptable. That was somewhat troubling.” Ghorashi suggests that manufacturers should be doing more to ensure consistency and adequate labeling of best-handling practices for consumers. “The message is that we need more awareness about the unknown risks and the potential need for more stringent safety measures,” he says. “We follow a great deal of these practices when it comes to meat-based products. Perhaps we’re not as sensitive toward veggie-based products.”

The report also uncovered several high-risk pathogens in samples, but not the typical ones (i.e., Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli) that make news headlines. Out of the 258 samples, 4.3% contained pathogenic DNA, with vegetable products accounting for four of those instances. Pathogens found included Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, Yersinia enterocolitica, clostridium perfringens, and klebsiella pneumonia. Although these strains are often rare, they still have health implications and can cause tuberculosis-like symptoms, digestive issues and gastroenteritis. Typical methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are used to detect pathogenic strains such as Listeria, Salmonella and E. coli, but can potentially miss other strains. “The industry should take off their pathogen blinders and start to test for lesser known and potentially dangerous pathogens using these types of blind-testing techniques,” says Ghorashi. “It’s worth casting a wider net and filter in order to catch these [pathogens].”

Although the screening method that Clear Labs used is currently unable to determine whether a pathogen is dead or alive, nor the count, there are other benefits to using next-generation DNA sequencing, says Ghorashi, who thinks the method has the potential to become the technology of choice in the food industry. “The strength of this platform as it differentiates itself from existing solutions is its ability to look unbiasedly and universally into food samples and tell you everything that’s there,” he says. “It’s able to detect any type of DNA-based species within a sample as opposed to specific queries that you might be looking for. This technology can detect everything that’s there, so it often catches things that one might miss. Existing solutions look very focused on one particular item.”

| What are the implications of The Hamburger Report in the context of FSMA?

Ghorashi: It’s very much in line with what FDA is rolling out with FSMA. This speaks back to where industry is headed in terms of rolling out more preventive measures versus responsive measures. It plays into economic adulteration and fraud. It also plays into the concept of proactive testing and measures, a better sense of the overall landscape of the supply chain and where the weaknesses are. These are all the areas that software-driven and data-driven platforms can help emphasize. We look at FDA as a forwarding-thinking organization and an ally in this initiative. Hopefully emerging companies, including ourselves, that have new disruptive technologies can help assist the food industry, whether producers, manufacturers, retailers or distributors, in building more air-tight safety programs and complying more closely with FSMA regulations. |

Clear Labs is working towards building out its first product, Clear View. The software data analytics platform integrates NGS technology and is designed to aggregate test data in the cloud to provide food manufacturers, suppliers and retailers with insights about their supply chains. The company is also continually growing its internal database, which, according to Ghorashi, is currently the largest molecular food database in the world.