In February, the European Union (EU) announced a proposed ban on the production, use, and sale of about 10,000 per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). We spoke with Craig Butt, Ph.D., Senior Staff Scientist for Food/Environmental Science at SCIEX to learn more about the proposal, how it may affect the food industry and how companies can begin preparing for more stringent regulations both in the EU and the U.S.

What do food companies need to know about the EU’s proposed ban on PFAS?

Butt: First, it is a proposal at this point and it is open to six-month commentary. About a year from now they will make an official decision. Whatever they decide will slowly be rolled out, but it is a huge and very comprehensive proposed ban that will impact people globally.

We live in an environment of global trade, so this will impact those that manufacture food packaging as well as any food products that might be coming across EU lines. What’s most interesting to me about this is the idea that, in the U.S. there’s a lot of attention on drinking water and drinking water regulations, but to propose banning PFAS in products, that takes the regulations further up the chain.

Is this a true ban on PFAS in the products or are they lowering the threshold from current levels?

Butt: There are two aspects to it. It would set lower limits, but they are also seeking more comprehensive monitoring. Typically, regulation and detection of PFAS has involved specific, targeted sets of compounds.

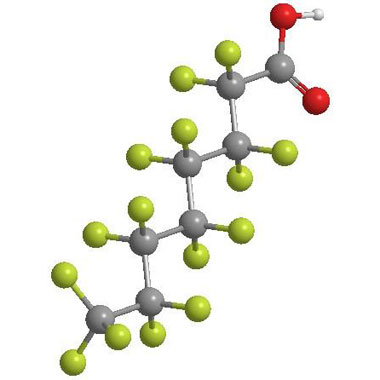

The problem with PFAS is, it is not like banning or reducing use of a single pesticide, you’re talking about potentially 5,000 different chemicals—depending on how you define them—and maybe even 12,000 different chemicals. So how do you address PFAS as a group? This proposal is trying to address that by looking at not only targeted compounds, but PFAS as a class and trying to understand the control of those compounds as a group.

There is still a lot of work to be done before we see where it falls out. The devil is always in the details, and I know there’s going to be pressure on multiple sides. You’re going to have pressure from one group saying this isn’t strict enough and the other side saying this is too strict and everyone’s going to go bankrupt.

But when you read it and you see the ban on products and certain thresholds in those products, I’m pretty sure that’s going to stay, particularly where they’re looking at total PFAS or total fluorine content. That tells us that we’re going to have to go beyond just looking for a targeted list of compounds and do a better job of characterizing all the fluorine compounds that are in there.

Does the proposal primarily focus on food contact packaging or the food products themselves?

Butt: There is still some clarity needed in terms of what the regulations will look like in the final document, but it seems to be focused more on the source, which would be the food packaging paper and products, rather than the food itself.

Where is the industry now in terms of detection and remediation of PFAS and where will it potentially need to go to meet these new regulations, if passed?

Butt: It is important to remember that there was a time before PFAS were widespread in food packaging, and I do know that companies are making efforts to look for alternatives. Back in the early 2000s when 3M banned Scotch Guard, it wasn’t too long until suitable alternatives were found. In the U.S., some manufacturers—working with the FDA—have agreed to change what’s in their food contact materials. In terms of what the industry has in the warehouse ready to go, it is unclear, but companies have seen the writing on the wall and are taking steps to find alternatives. Still, the move totally away from fluorochemicals will likely be a bit of a shock to those who make them.

The concerns will be whether the non-fluorinated chemicals are as effective as the PFAS, and if they are not will they still be satisfactory? We also need to be cautious as we investigate alternatives because we don’t want to replace these PFAS chemicals with newer chemicals that we don’t yet have knowledge about their toxicology or environmental impact on.

What should people looking at now in terms of investigating new products and understanding what they’re going to need to do in terms of detection?

Butt: Detection is the first step. Some folks may not be aware of what’s in the products they are buying in terms of raw materials. You want to know what’s in your own products and the products you are using. There is a huge risk in terms of public relations and reputation. The last thing a company wants to do is have a third party test their products and find out that there are PFAS in them and have that potential reputational damage, because there are a lot of third parties out there that do that, and they are not afraid to name names.

Are there effective tests available if you want to start checking your packaging?

Butt: Yes, we have gotten very good at measuring extremely low levels as well as reducing some of the impacts on data quality and detection in terms of confirmed detection. We can measure things at trace levels and accurately say that they are there. That’s from a targeted standpoint. But we’re also very good at doing non-targeted work to find some of those unknown PFAS that may not be on a standard monitoring list but can help improve the further characterization of what’s there.

A lot of attention has been on PFOS and PFOA, but if you are only looking at those compounds, then you are doing yourself a disservice because what we know and what we’ve seen through time is that those lists of dangerous compounds only continue to grow. As regulators become aware of their presence and their toxicology and as analytical chemists get better and publish findings of these new compounds in consumer products, then the list will continue to grow.

In terms of the regulatory climate here in the U.S., where do you think we’re headed?

Butt: Back in the late 2000s, the FDA scientists produced some really incredible work looking at PFAS in food packaging and their migration out of that packaging into foods, and we continue to work with them. They are great scientists and they published some groundbreaking research. However, these are not the same scientists who make the regulations.

There have been some voluntary agreements with some of the manufacturers to reduce the use of chemicals that are larger—the long chain compounds—which are more likely to accumulate in human blood. But these EU regulations will put a whole lot more pressure on companies to look at PFAS as a larger class of chemicals.

As companies look for alternatives that are a) effective and b) not dangerous, are leaching tests typically part of testing these new products?

Butt: The EU regulations do have a leaching component for some of the food packaging materials, particularly for plastic food packaging. You do need to assess the leaching from plasticizer compounds. I’m not sure if there’s a similar leeching test for PFAS, because PFAS are a little bit weird in the sense that, in the past, most of the chemicals that we were concerned about were those that were fat soluble. We know that fatty foods like yogurts are very good at pulling out the contaminants from the food packaging, but PFAS are a little bit odd because they like more neutral compounds, ones that have some emulsifying properties to them—not super fatty or super water soluble—so you have to be cautious that the right kind of migration tests are being used and are fully applicable for these compounds.

One of the things that makes PFAS so interesting is that they don’t behave like our traditional hydrophobic organic contaminants. They don’t build up in your fat. Years ago, when we were worried about DDT and PCBs and some of those other chlorinated pesticides it was because they build up in your fat. But PFAS build up in the blood, kidney and liver, which from a chemical standpoint is interesting but it also means that some of our tests have to be revised for them.

But the really big thing is, with all the PFAS that are out there, the onus now seems to be shifting on to the manufacturer to know what is in their products beyond just the big ones of PFOS and PFOA. I think that is where we’re going in terms of the testing market. It’s not just testing for individual compounds, but doing a total PFAS analysis at a screening level and then, if a product is above a certain threshold, we do a more targeted, specific analysis.