Ensuring the safety and authenticity of food is a key responsibility of growers, producers, manufacturers and suppliers. With so many partners involved in the journey from farm to fork, tracking chain of custody data and maintaining a clear, unbroken record are essential to safeguard the quality and provenance of products. However, without proper systems to maintain transparent supply chain audit trails, businesses operating within the food industry run the risk of being responsible for adverse events that could result in health, economic or even legal consequences.

One of the biggest challenges associated with maintaining a clear chain of custody is the need to monitor the flow of raw materials, ingredients and products across increasingly global distribution networks. To successfully track food products throughout the value chain, information on product movements and quality control data must be accessible to those who need it. These systems must also remain compliant with the latest regulations, as well as ensure stakeholders can achieve the highest levels of productivity to meet consumer demand.

For players within the food supply chain to achieve transparent processes and complete traceability, robust information exchange mechanisms and integrated data management systems are key. The latest digital solutions are ensuring the integrity of supply networks by capturing and making available data from any stage of this journey for regulatory or product quality assurance purposes.

Food Safety: A Global Responsibility

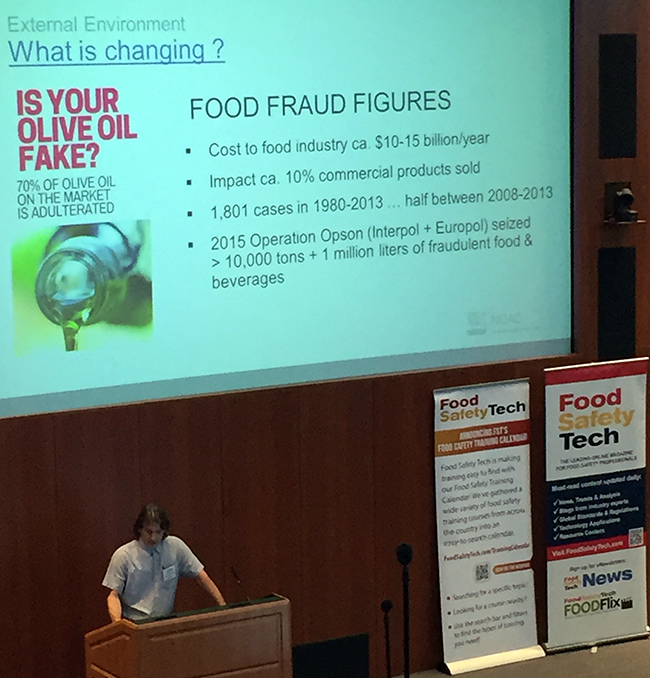

The global nature of modern supply networks can make ensuring the safety and quality of food challenging. From honey and juice to yogurt and cheese, tracking the lifecycle of food products is essential to combat food fraud and adulteration, as well as safeguard consumers from harmful food contaminants, such as pesticides and bacteria. Unscrupulous behavior from businesses operating within the supply chain can, for example, cause consumers to purchase products that are not what they claim to be, and even put customers’ health at risk through exposure to potentially unsafe batches.

Given the global expansion of the food supply chain, regulatory bodies are putting increased focus on ensuring that products that pass through multiple channels and regions comply with the same regulations. By focusing on enforcing standards through audits and reviews, it becomes possible to prevent and therefore reduce the potential for adverse events occurring.1 As a result, voluntary standards such as the ISO 22000 guidelines, and mandatory regulations such as FSMA and EU 178/2002, have been put in place to set clear benchmarks for stakeholders’ responsibilities and better enforce food quality and safety.

Regulations such as these require extensive record keeping, transparent audit trails and accountability for all processes. While end-to-end monitoring of one process may be relatively straightforward, ensuring visibility for every process within a complex food supply network can quickly become an overwhelming task. In order to achieve regulatory compliance across all aspects of a supply chain, businesses must be able to integrate their data management systems to achieve full oversight. Moreover, with effective data management tools in place, businesses can organize and incorporate data from all aspects of a food product lifecycle in a compliant manner, enabling them to expand globally.

Integrating Digital Solutions for Better Outcomes

To preserve consumer confidence and brand integrity, businesses operating within the food industry are recognizing the need for automated infrastructures that can manage data, streamline processes, and ensure traceability and accountability for every product. By integrating all monitoring processes into a single system and enabling access to this information via the cloud, the latest digital data management platforms are working to alleviate the challenges associated with operating global supply networks.

Manually organizing inventory management, standard operating procedure (SOP) use, and product traceability can be difficult and time-consuming, especially if operations are on a global scale. Setting up automated processes to manage fail points using a laboratory information management system (LIMS), where they can be itemized and protocols established for potential hazards and preventive measures, can boost speed and efficiency while ensuring the highest levels of data integrity.

Routine food safety testing requires the consistent replenishment of supplies, and the failure to keep on top of inventory use can cause operations to grind to an unexpected stop. Automatic supply level monitoring and automated ordering using a LIMS can eliminate inventory fail points and help to ensure uninterrupted productivity. Furthermore, introducing electronic SOPs as part of a LIMS can define and outline workflows to prevent unintended errors and ensure reliability. Additionally, tracking and logging products using barcode readers throughout their lifecycle gives stakeholders confidence in the products they handle, and can simplify quality control and regulatory review processes.

With the need to monitor so many processes across the food supply chain, there are large volumes of instrument data, workflows and records that must be maintained. Leveraging a LIMS to collect and manage disparate data from all aspects of every process can help stakeholders to streamline workflows. From evaluating potential hazards to eliminating possible issues, having procedures tracked automatically not only transforms processes, but also simplifies quality assessment.

The latest LIMS are able to aggregate all of this data in a single cloud-based system, making this information available at the tap of a tablet or smartphone. Integrating a LIMS with laboratory equipment across food safety testing protocols allows for automated data transfer and increased lab efficiency. Data can be captured from laboratory equipment using a connected scientific data management system (SDMS), which is generated using the approved methods and SOPs available from a laboratory execution system (LES). Interfacing to each instrument using the LES ensures there are no input or copying errors. Subsequently, as process results are entered into the system, any out of specification parameters can be flagged and reported automatically.

The value of an LES within a LIMS can be seen in food safety labs where global demand drives time to market and thus the need for high production efficiency. By giving lab managers control over method and protocol management from any location, the actions of users can be easily recalled for performance monitoring and accountability purposes. And with protocols, regulations and corrective actions defined through the LIMS, labs can achieve faster and more effective decision-making.

Digital solutions such as LIMS are enabling food safety scientists to perform analyses based on readily available SOPs using LES platforms, collect and store data in its original form using an SDMS, and evaluate how the data is being collected, transferred, stored and accessed from a centralized, cloud-based LIMS. These integrated digital solutions offer comprehensive support for the organization of chain of custody data, ensuring full traceability and compliance, and protecting consumer safety and food integrity.

Improved Traceability for Regulatory Compliance

Current regulations are enforcing the quality and safety of food products using well-defined standards for laboratory processes, ensuring the transparency of data handling processes, from raw materials to packaged products. ISO 22000 sets recommendations for food safety management systems and requires businesses to implement hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP) to ensure the highest levels of quality control and assurance throughout the product lifecycle.

Regulations such as EU 178/2002 and FSMA include mandatory requirements for the traceability of food, feed and any other food-related substance or animal through identification and food tracking programs. Given the unfortunate growth of food fraud, traceability and authentication are becoming increasingly important. The latest regulations are helping the food industry to maintain optimal production practices to safeguard public health, maintain consumer confidence and preserve brand integrity.

Systems that are fully harmonized with these guidelines can be used to maintain data in organized archives, simplify audit trail recording for proof of compliance, and enable easy-access for users to review data. The latest LIMS can support HACCP compliance by automatically alerting users to deviations in expected processing parameters. In this way, issues can be quickly identified, and corrective action can be taken to prevent potentially dangerous products from reaching the consumer.

Digital lab and data management solutions are helping food supply chain stakeholders to simplify tracking, improve transparency and ensure the highest levels of accountability to protect both product authenticity and consumer safety. The integration and implementation of these systems helps to fulfill production demands as well as meet future challenges, allowing the food industry to expand and develop services and checks with the growing global market. Moreover, the potential for food fraud or adulteration is greatly minimized, giving consumers additional confidence in the products they purchase.

Reference

- Charlebois, S. Sterling, B. Haratifar, S. and Naing, S.K. (2014). “Comparison of Global Food Traceability Regulations and Requirements,” Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf., vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 1104–1123.