Burgers are the quintessential American food. But as prices continue to rise in the beef industry and U.S. consumers seek more health-conscious alternatives such as veggie and salmon burgers, some food companies may be cutting corners. Clear Labs used next-generation genomic sequencing (NGS) to conduct molecular analysis of 258 burger products (ground meat, frozen patties, fast food burgers and veggie burger products from 79 brands and 22 retailers) and found significant issues—instances of substitution, missing ingredients, pathogens or hygienic problems—in about 14% of samples. This is a red flag for industry, indicating a need to remain vigilant about vulnerabilities in the supply chain and the way in which products are tested.

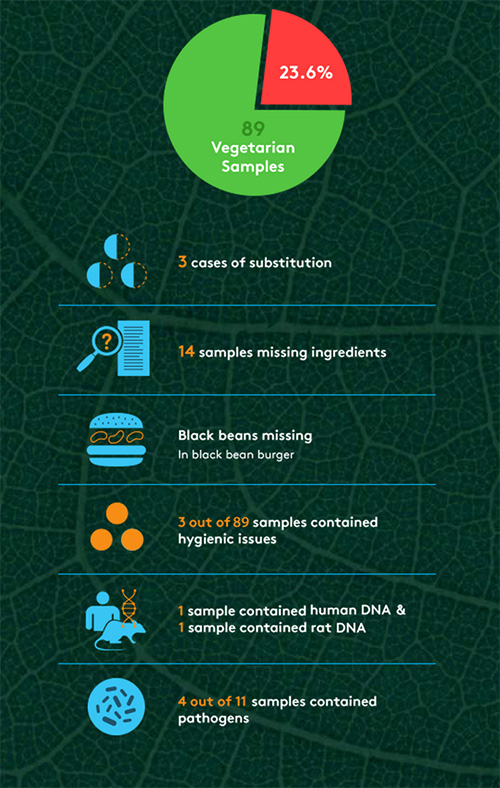

Ironically, perhaps the biggest problems that The Hamburger Report revealed surrounded meat-alternative products. Out of 89 vegetarian samples, 23.6% were found to have issues, from ingredient substitutions to rat DNA to pathogens (see Figure 1). “We were surprised by the higher rate of problems in veggie burgers,” says Mahni Ghorashi, co-founder of Clear Labs. “There were nearly twice as many problems in those samples as their meat counterparts, which is surprising, because you normally think of a veggie product as perhaps a safer bet, but we actually found more cases of pathogen strains. And we found things like beef in veggie products, which isn’t acceptable. That was somewhat troubling.” Ghorashi suggests that manufacturers should be doing more to ensure consistency and adequate labeling of best-handling practices for consumers. “The message is that we need more awareness about the unknown risks and the potential need for more stringent safety measures,” he says. “We follow a great deal of these practices when it comes to meat-based products. Perhaps we’re not as sensitive toward veggie-based products.”

The report also uncovered several high-risk pathogens in samples, but not the typical ones (i.e., Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli) that make news headlines. Out of the 258 samples, 4.3% contained pathogenic DNA, with vegetable products accounting for four of those instances. Pathogens found included Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, Yersinia enterocolitica, clostridium perfringens, and klebsiella pneumonia. Although these strains are often rare, they still have health implications and can cause tuberculosis-like symptoms, digestive issues and gastroenteritis. Typical methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are used to detect pathogenic strains such as Listeria, Salmonella and E. coli, but can potentially miss other strains. “The industry should take off their pathogen blinders and start to test for lesser known and potentially dangerous pathogens using these types of blind-testing techniques,” says Ghorashi. “It’s worth casting a wider net and filter in order to catch these [pathogens].”

Although the screening method that Clear Labs used is currently unable to determine whether a pathogen is dead or alive, nor the count, there are other benefits to using next-generation DNA sequencing, says Ghorashi, who thinks the method has the potential to become the technology of choice in the food industry. “The strength of this platform as it differentiates itself from existing solutions is its ability to look unbiasedly and universally into food samples and tell you everything that’s there,” he says. “It’s able to detect any type of DNA-based species within a sample as opposed to specific queries that you might be looking for. This technology can detect everything that’s there, so it often catches things that one might miss. Existing solutions look very focused on one particular item.”

| What are the implications of The Hamburger Report in the context of FSMA?

Ghorashi: It’s very much in line with what FDA is rolling out with FSMA. This speaks back to where industry is headed in terms of rolling out more preventive measures versus responsive measures. It plays into economic adulteration and fraud. It also plays into the concept of proactive testing and measures, a better sense of the overall landscape of the supply chain and where the weaknesses are. These are all the areas that software-driven and data-driven platforms can help emphasize. We look at FDA as a forwarding-thinking organization and an ally in this initiative. Hopefully emerging companies, including ourselves, that have new disruptive technologies can help assist the food industry, whether producers, manufacturers, retailers or distributors, in building more air-tight safety programs and complying more closely with FSMA regulations. |

Clear Labs is working towards building out its first product, Clear View. The software data analytics platform integrates NGS technology and is designed to aggregate test data in the cloud to provide food manufacturers, suppliers and retailers with insights about their supply chains. The company is also continually growing its internal database, which, according to Ghorashi, is currently the largest molecular food database in the world.

I’m surprised you didn’t check the internet:

http://www.snopes.com/clear-foods-hot-dog-dna-study/

This is part of my reply to the NY Times (They decided not to publish the article)

My previous and the following comments are not to dismiss the

probability of intentional or accidental adulteration or misbranding.

There is a long history of economic adulteration. For instance

watering down milk was countered by using hydrometers to measure

density; that was countered by adding cow urine, which was countered

by measuring protein with Kjeldahl analysis, that was most recently

countered by adding melamine, which was discovered by killing people.

Then there is intentional, accidental, or malicious adulteration by

workers. A quick search for recalls due to plastic or glass in foods

(metal detectors are almost universal) will yield several instances.

Still, the issue of highly sensitive last generation PCR or “next

generation genetic sequencing” has raised the question of “How much is

significant?” over the past two decades.

Two comments from experts:

A: Given the findings of Kane and Hellberg, it’s not surprising that

“foreign” DNA has been found in beef patties. While the presence of

rodent and human DNA is disquieting, they might be at such low levels

to be a de minimus hazard. As far as I know, neither FDA nor FSIS

routinely look for “foreign” DNA as the presence of other meat DNAs

might be considered an economic issue, and while the products could be

considered misbranded, it doesn’t seem to be a big health issue unless

someone has a allergic sensitivity. At for FDA, economic fraud was

put on the back burner in the late 90s (see the Regulatory Fish

Encyclopedia as an example of a project that was cancelled) and I

guess religious issues weren’t considered to be important enough to

make sure pork wasn’t mixed in with beef.

With regard to contaminants like rodent hairs, FDA has set

tolerances (called Defect Action Levels) for various combinations of

contaminants and products, for example, rodent hairs in peanut butter

and mold hyphae in ketchup.

I don’t think I’m telling you much of anything that you don’t already know.

Human DNA from feces, spit or vomit can’t be discounted………..”

B: “I’d like to know more about the analysis. She said they were

using next generation sequencing, but if they did detect rodent DNA ,

they must have been using some version of PCR. That’s because there

would only be trace amounts of rodent DNA in the meat. We’re not

talking about rodent burgers, we’re only talking about very minute

traces of rodent DNA, if that’s what it is. And in that case, the

chicken and pork DNA may also just be traces that were amplified.

I’m also curious how they distinguished bison and beef DNA. A lot

of animals that look like bison may have cattle DNA from

cross-breeding in previous generations.

Also, she said that the beef burgers had proteins from other

species. But no proteins were found in the meat, only DNA, which as I

said, appears to be amplified.

For a forensics example, I can shake hands with you, then I can

pick up a murder weapon, and your DNA will then be on the murder

weapon, which is detected after amplification. There was a recent

murder case where something similar happened and an innocent person

was convicted based on the DNA evidence.

I wouldn’t believe their findings unless I knew more about the

analysis, and a one-sentence description is not enough. ”

Then there is:

Cornell University food scientist Martin Weidmann has another explanation. “This is most likely a result of issues with analyzing large data sets, which can easily lead to erroneous results,” Weidmann told Gizmodo in an email. In an article published in Food Safety Magazine*, Weidmann warns would-be food testers about the pitfalls of interpreting metagenomic results, including the high potential for false positives.

*http://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/magazine-archive1/junejuly-2015/use-of-whole-genome-sequencing-in-food-safety/