When a business decides to invest in technology, the primary driver is usually to save money over the long term. As with most automated systems, inventory management tools can reduce costs by saving time and resources used to manage inventory.

But the benefits that automated inventory tracking can provide through traceability (of lots, batches, and even individual items) go beyond the financial. These systems can also be used in every aspect of your food safety program from helping with compliance, to improving your quality controls.

Exchange knowledge about managing your supply chain at the Best Practices in Food Safety Supply Chain conference | June 5–6, 2017 | LEARN MORE

In a nutshell, having an automated system that allows full visibility into the supply chain—that is, one that identifies in real time where items are being used and where they are sent, while retaining a historical record of that flow through the chain—makes it much simpler and faster to implement procedures to ensure the safety of the food you produce.

All about Accuracy and Speed

Speed and accuracy make a huge difference when it comes to dealing with potentially contaminated food. Being faster and more accurate than a manual inventory method is the most immediate benefit that an automated system brings to your food safety program.

The most compelling reason for having accurate and readily accessible track-and-trace data is to handle food recalls and to comply with requests for documentation from government agencies such as the FDA. In cases where consumer health is at risk, that information needs to be delivered quickly to prevent further harm, and it must be accurate to enable investigators to move in the right direction. Responding to requests for detailed documentation within a 24-hour timeframe can be nearly impossible if you are not using an automated system.

Even when the situation doesn’t involve a federal investigation, once a situation in which possible contamination or mislabeling arises, the faster you have accurate and detailed data, the faster your internal processes can move forward.

If the issue is identified through your quality control process, you will be more likely to be able to prevent contaminated product from reaching the retail outlet and thus getting into the hands of the consumer. Having traceability built into your inventory management systems provides immediate knowledge about whether a product using ingredients from the same batch have entered the distribution chain, and if so, where they are going. This greatly improves the likelihood of limiting the cost and scope of a recall.

Depending on the specific technology you employ, an automated system can provide immediate access to the track and trace information for specific ingredients at least one step backward and one step forward, as required by the Bioterrorism Act of 2002. A supply chain that integrates the most sophisticated technology, such as DNA tracking, can trace an item all the way from the farm or border to the individual consumer or restaurant kitchen.

This traceability means that if an ingredient was already contaminated before it entered your production line, the inventory tracking system can identify all products using that ingredient from the contaminated lot and thus will help you define the scope of the problem. This automation can go a step further by identifying where the ingredient lot originated, and thus help trace the ingredient at least one step backward to the vendor. If the vendor (whether a distribution company or a direct supplier) has traceability in an automated system, or if you are using a system hosted by a distribution partner, tracing the source farther back than one step is possible.

Such information can help you respond more quickly to FDA requests for product information and support the agency’s efforts in product traceability.

Protect Your Reputation

Just as using tracing technology can help identify potential contamination sources quickly, it can also be used to eliminate sources more quickly and accurately, thereby speeding up investigations into food contamination incidents. The faster a company can be eliminated from an investigation, the less time is taken away from normal production. In addition, quick exclusion can protect a company’s reputation from harm.

Additional Benefits

Through their ability to store specific data that can be used to identify potential risks, automated track and trace systems contribute to many preventive food safety measures as well as to the following corrective responses:

- For perishable products, automated traceability can identify how long specific perishables have been in supply chain. This allows you to avoid using ingredients close to spoilage and to remove overdue products from the distribution chain.

- During mock recalls, automated tracking systems reduce the time spent away from regular production and allow you consistent information throughout the organization, eliminating wasted effort due to miscommunications.

- Automated systems reduce the time needed for notifications both internally and externally in the case of an incident affecting food quality or safety. This leads to faster line clearance and faster isolation of the possibly contaminated product.

- With more effective accounting for possibly affected batches, you can better identify where to apply cleanup measures in the production chain.

In short, automated tracking can improve implementation of preventive controls to stop the contaminated product from reaching the marketplace, and in cases in which corrective actions are required, the automated system can help you respond more quickly and can reduce the scope of risk.

Not just Foodstuffs

Although raw ingredients and food products obviously require traceability, they aren’t the only traceable inventory that can impact food safety. Automated lot tracking can enhance food safety efforts related to all inventory items used in food processing/manufacturing:

- Packaging. A sub-standard packaging lot can allow incursion of harmful substances or the growth of harmful bacteria. Leakers can contaminate an entire batch of meat or poultry product. Automated lot tracking can help you rapidly isolate the bad lot and know which production lines have already used the sub-standard materials.

- Labeling. If an inferior adhesive has been applied to a batch of labels, you can identify which product lots to pull from the distribution chain. You can do the same if your quality controls find a batch of inaccurate labels.

- Protective equipment and clothing. Gloves, masks and other protective gear must function properly to ensure the safety of your workers and also to prevent contamination from being introduced on the production line. An inferior batch of protective gloves that tear during use, for example, could violate your food safety practices. Identifying the bad batch quickly and removing it from the operations area immediately can save potential contamination.

- Cleaning solutions. Even a batch of cleaning solution can be sub-par. If tests show that cleaning has not eliminated the targeted bacteria, for example, you can more quickly take measures to determine whether the root cause of the problem was a procedural issue or a quality issue with the batch of cleaner.

Beyond the Production Line

The benefits of automated tracking systems to your food safety program extend beyond the production line. They can also enhance decision-making, vendor management and communications functions.

When it comes to potential contamination, decision making needs to be both timely and based on the best information available. Automated systems can provide you with accurate information quickly to help you answer these and other key questions, so that the decision on what actions to take can be based on good information:

- How widespread is the potential contamination?

- Where is the product in the production and distribution chains?

- Have we already exposed consumers?

These systems can put the answers to these questions in front of the appropriate decision makers early in the process. The technology can be configured to allow access to the data via a browser, so if those who make the final decisions are located elsewhere, they can see in real time the same information that you are seeing in the plant. This makes communication about potential contamination more effective and clear, since everyone can see the same thing at the same time, and it can eliminate the potential for miscommunication up the chain of command.

By identifying where bad lots entered your supply chain, automated track-and-trace can enhance supplier accountability. You can accurately see if you have vendors with recurring issues in the quality of the supplies they are providing.

Automated Inventory Tracking Technologies

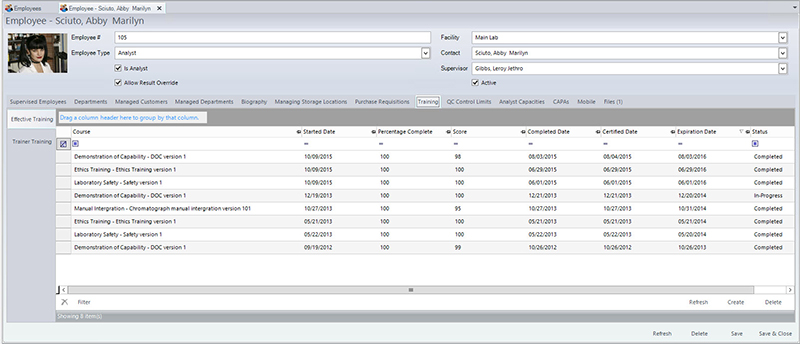

An automated inventory tracking system depends on three components:

- A physical component, such as a label or tag, which contains detailed information identifying the specific lot or item.

- A database, where each discrete data item is stored.

- A reporting interface that allows people to access and use the identification information. This is the programming code that performs searches, retrieves the data, and formats the information in a formatted report, which is then presented on the screen, saved to a file, or sent to a printer.

The most common physical components used by automated inventory tracking systems rely on barcode or RFID technology, or a combination of both. The choice of which technology to use to integrate into the inventory management database layer of the system depends on a number of factors, but both have been proven extremely accurate (some sources say up to 99%). What is more important than the choice of tracking tools is the quality of the data encoded in them.

The latest in tracking technology uses an engineered DNA marker, in the form of an edible spray. When applied to produce, this DNA marker can track the individual item (i.e., an apple, head of lettuce or onion), along the entire food supply chain, identifying where it was farmed, the date it was picked, and where it was processed.

Whatever form of technology you employ, ensuring that your data is complete and accurate and can be integrated into both your supply and distribution chain is critical to realizing the benefits of that system in supporting your food safety efforts.

The WDS Food Safety Team also contributed to this article.