As the movement among consumers for more information about the products they’re purchasing and consuming continues to grow, the food industry will experience persistent pressure from both advocacy groups and the government on disclosure of product safety information and ingredients. Top of mind as of late has been the debate over GMOs. “Given all of the attention on GMOs on the legislative side, there is huge demand from consumers to have visibility and transparency into whether products have been genetically modified or not,” says Mahni Ghorashi, co-founder of Clear Labs.

Today Clear Labs announced the availability of its comprehensive next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based GMO test. The release comes at an opportune time, as the GMO labeling bill, which was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives last week, heads to the desk of President Obama.

Clear Labs touts the technology as the first scalable, accurate and affordable GMO test. NGS enables the ability to simultaneously screen for multiple genes at one time, which could companies save time and money. “The advantage and novelty of this new test or assay is the ability to screen for all possible GMO genes in a single universal test, which is a huge change from the way GMO testing is conducted today,” says Ghorashi.

The PCR test method is currently the industry standard for GMO screening, according to the Non-GMO Project. “PCR tests narrowly target an individual gene, and they’re extremely costly—between $150–$275 per gene, per sample,” says Ghorashi. “Next-generation sequencing is leaps and bounds above PCR testing.” Although he won’t specify the cost of the Clear Labs assay (the company uses a tiered pricing structure based on sample volume), Ghorashi says it’s a fraction of the cost of traditional PCR tests.

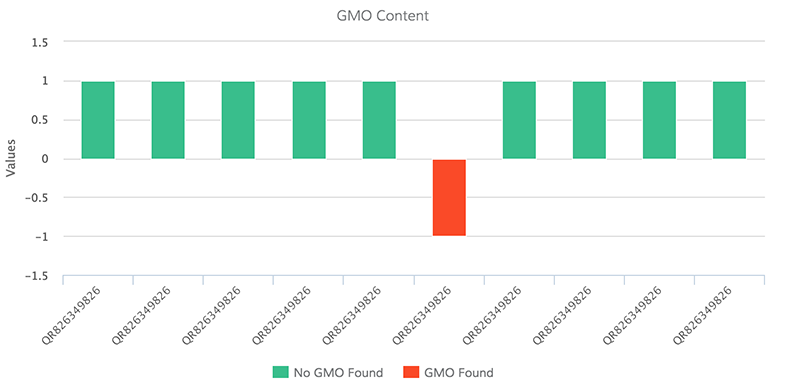

The new assay screens for 85% of approved GMOs worldwide and targets four major genes used in manufacturing GMOs (detection based on methods of trait introduction and selection, and detection based on common plant traits), allowing companies to determine the presence and amount of GMOs within products or ingredient samples. “We see this test as a definitive scientific validation,” says Ghorashi. The company’s tests integrate software analytics to enable customers to verify GMO-free claims, screen suppliers, and rank suppliers based on risk.

Clear Labs isn’t targeting food manufacturers of a specific size or sector within the food industry but anticipates that a growing number of leading brands will be investing in GMO testing technology. “We expect to see adoption across the board in terms of company size, related more to what their stance is on food transparency and making that information readily available to their end consumers,” says Ghorashi.