Cryptocurrency is a favorite topic in the business world currently, but it’s not the coins or currency that are the star of the show. Bitcoin in and of itself is exciting and promising from several perspectives. However, the foundation of what these technologies run on is much more important. You likely already know what we’re going to talk about next: Blockchain.

To understand why blockchain is considered so crucial, you first need to delve into the core components of the technology. It’s basically a digital ledger, except it has some incredibly useful properties that make it uniquely lucrative. For starters, it’s public and transparent, so anyone with access to the network can see what’s happening in the moment, or what has been happening while they were away. However, the parties involved in a transaction or entry remain private, as do the materials or items exchanging hands.

Finally, because of the nature of blockchain, it’s secured and valid. The ledger itself is thoroughly protected, and no one can alter data save the parties involved. Even then, the relevant parties only weigh in with pertinent information such as time and date of the transaction and the amount transferred.

Most of what we’re talking about here is in reference to currencies and more traditional transactions. But it’s important to remember that we’re merely scratching the surface. As we speak, various organizations are working to adapt this technology for alternate industries and applications.

Still, what does any of this have to do with your average food supply chain?

Blockchain May Evolve the Food Supply Chain As We Know It

Believe it or not, blockchain can help improve the transparency and management of the food supply chain. It’s definitely needed. The world’s population continues to grow, and it’s expected to reach 10 billion by 2050. In food requirements, that means we’ll need to be increasing food production by as much as 70% to keep up. This puts a demand on the food supply chain to evolve and become more efficient, more accurate and more reliable.

The following are several ways blockchain can help achieve better transparency in and management of the food supply chain.

Preventing Foodborne Outbreaks, Enabling Fresher Goods

IBM has teamed up with several major suppliers including Wal-Mart, Dole and Nestle to come up with a blockchain-powered system that can be used to track a product’s journey from farm to store shelves. The goal is to create a more transparent deployment and transportation process so that interested parties can see exactly when and where certain foods might become contaminated.

Tracking this information will achieve a couple of things. For starters, public health officials, suppliers and management teams can help limit and prevent contagions from spreading. After the detection of Salmonella, for instance, they could mark all related goods as a risk and stop both stores from selling them and consumers from buying faster than ever before.

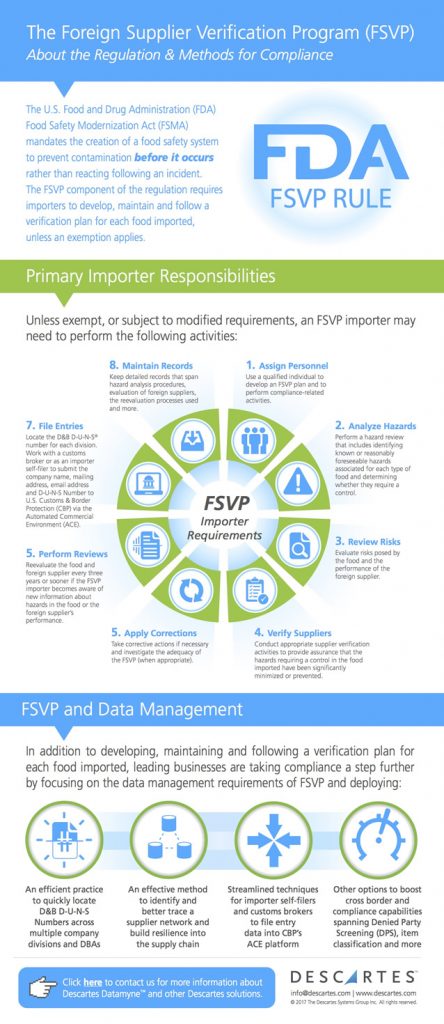

Second, it will help identify problematic systems and processes, hopefully cutting down on the risk of contamination in the future. If they know certain foods are going bad in transport, they can discern that it’s something to do with how they’re handled or stored along that segment of the journey. This would further enable them to identify and fix or optimize the issue. In other words, suppliers and retailers will use blockchain to keep food fresh. This is especially important since FSMA calls for reliable hygiene and storage methods during transportation.

More Accurate Inventory Tracking for Distributors

Unexpected shortages pose significant challenges to the food supply chain. A variety of external factors can contribute to a supply block, including inclement weather, poor soil, insect infestations, equipment failures and much more. When this happens, distributors are left to pick up the slack, but sadly, they often can’t do much to fix the problem.

Blockchain technologies, however, make the supply chain more transparent, which helps distributors get the information they need to address shortages. Through the use of blockchain, they’ll know exactly how much supply is available and what they need to do to ramp up their offerings.

For example, in the event of a shortage, they might connect with local farmers to make up the difference. Gathering the information needed to find the right partner, however, can take a long time when using traditional methods. Through blockchain, though, distributors could easily see product types, farming practices, harvest dates and amounts, treatment info, fair-trade certifications and other information. This would allow them ample time to find a suitable replacement or additional partner.

Transparent Safety Protocols

The food supply chain is lengthy, includes a lot of different parties and involves a lot of metrics and details that need to be recorded and monitored. The problem with having so many factors is that it can muddy the waters. It’s hard to keep track of what every party is doing, where problems exist and what improvements can be made.

Many modern food supply providers are as transparent as they can be with partners and colleagues, but it’s not an element you would describe as streamlined or accessible to all. Blockchain can completely alter and disrupt this for the better.

Since food safety is an enormous concern for suppliers, distributors and retailers, blockchain can offer more than just peace of mind. It can help organizations perfect the entire process, improving safety for consumers and even enhancing the freshness or quality of the products provided. Improper storage or transport, for instance, can have a detrimental effect on quality, before the goods even reach store shelves. Blockchain will enable better tracking and monitoring, and make the resulting details much more accessible and transparent.

It’s Time for the Food Supply Chain to Evolve

The coming change is warranted and welcomed by many. A more transparent process means a much more accessible system. Suppliers can better communicate with farmers and food sources. Distributors and retailers can keep a close eye on the goods they’re acquiring and offering to consumers. Furthermore, safety, quality and quantity can be more accurately monitored and measured by everyone along the way. It’s time for the food supply chain to evolve in this way — it’s been a long time coming.