Traditional approaches to food safety no longer make the grade. It seems that stories of contaminated produce or foodborne illnesses dominate the headlines increasingly often. Some of the current safeguards set in place to protect consumers and ensure that companies are providing the freshest, safest food possible continue to fail across the world. Poorly regulated supply chains and food quality assurance breakdowns often sicken customers and result in recalls or lawsuits that cost money and damage reputations. The question is: What can be done to prevent these types of problems from occurring?

While outdated machinery and human vigilance continue to be the go-to solutions for these problems, cutting-edge intelligent imaging technology promises to eliminate the issues caused by old-fashioned processes that jeopardize consumer safety. This next generation of imaging will increase safety and quality by quickly and accurately detecting problems with food throughout the supply chain.

How Intelligent Imaging Works

In broad terms, intelligent imaging is hyperspectral imaging that uses cutting-edge hardware and software to help users establish better quality assurance markers. The hardware captures the image, and the software processes it to provide actionable data for users by combining the power of conventional spectroscopy with digital imaging.

Conventional machine vision systems generally lack the ability to effectively capture and relay details and nuances to users. Conversely, intelligent imaging technology utilizes superior capabilities in two major areas: Spectral and spatial resolution. Essentially, intelligent imaging systems employ a level of detail far beyond current industry-standard machinery. For example, an RGB camera can see only three colors: Red, green and blue. Hyperspectral imaging can detect between 300 and 600 real colors—that’s 100–200 times more colors than detected by standard RGB cameras.

Intelligent imaging can also be extended into the ultraviolet or infrared spectrum, providing additional details of the chemical and structural composition of food not observable in the visible spectrum. Hyperspectral imaging cameras do this by generating “data cubes.” These are pixels collected within an image that show subtle reflected color differences not observable by humans or conventional cameras. Once generated, these data cubes are classified, labeled and optimized using machine learning to better process information in the future.

Beyond spectral and spatial data, other rudimentary quality assurance systems pose their own distinct limitations. X-rays can be prohibitively expensive and are only focused on catching foreign objects. They are also difficult to calibrate and maintain. Metal detectors are more affordable, but generally only catch metals with strong magnetic fields like iron. Metals including copper and aluminum can slip through, as well as non-metal objects like plastics, wood and feces.

Finally, current quality assurance systems have a weakness that can change day-to-day: Human subjectivity. The people put in charge of monitoring in-line quality and food safety are indeed doing their best. However, the naked eye and human brain can be notoriously inconsistent. Perhaps a tired person at the end of a long shift misses a contaminant, or those working two separate shifts judge quality in slightly different ways, leading to divergent standards unbeknownst to both the food processor and the public.

Hyperspectral imaging can immediately provide tangible benefits for users, especially within the following quality assurance categories in the food supply chain:

Pathogen Detection

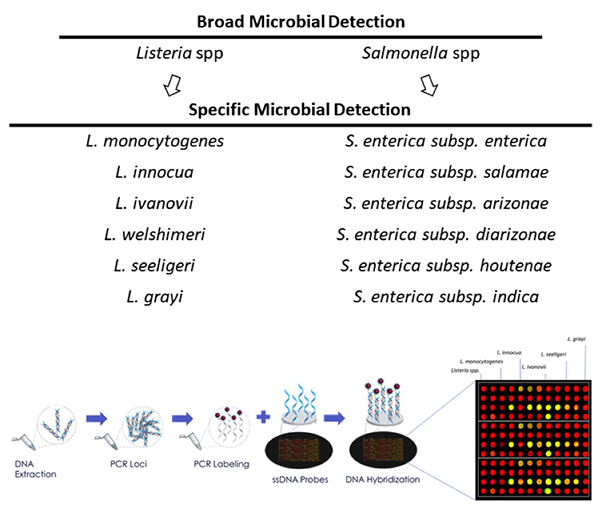

Pathogen detection is perhaps the biggest concern for both consumers and the food industry overall. Identifying and eliminating Salmonella, Listeria, and E.coli throughout the supply chain is a necessity. Obviously, failure to detect pathogens seriously compromises consumer safety. It also gravely damages the reputations of food brands while leading to recalls and lawsuits.

Current pathogen detection processes, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunoassays and plating, involve complicated and costly sample preparation techniques that can take days to complete and create bottlenecks in the supply chain. These delays adversely impact operating cycles and increase inventory management costs. This is particularly significant for products with a short shelf life. Intelligent imaging technology provides a quick and accurate alternative, saving time and money while keeping customers healthy.

Characterizing Food Freshness

Consumers expect freshness, quality and consistency in their foods. As supply chains lengthen and become more complicated around the world, food spoilage has more opportunity to occur at any point throughout the production process, manifesting in reduced nutrient content and an overall loss of food freshness. Tainted meat products may also sicken consumers. All of these factors significantly affect market prices.

Sensory evaluation, chromatography and spectroscopy have all been used to assess food freshness. However, many spatial and spectral anomalies are missed by conventional tristimulus filter-based systems and each of these approaches has severe limitations from a reliability, cost or speed perspective. Additionally, none is capable of providing an economical inline measurement of freshness, and financial pressure to reduce costs can result in cut corners when these systems are in place. By harnessing meticulous data and providing real-time analysis, hyperspectral imaging mitigates or erases the above limiting factors by simultaneously evaluating color, moisture (dehydration) levels, fat content and protein levels, providing a reliable standardization of these measures.

Foreign Object Detection

The presence of plastics, metals, stones, allergens, glass, rubber, fecal matter, rodents, insect infestation and other foreign objects is a big quality assurance challenge for food processors. Failure to identify foreign objects can lead to major added costs including recalls, litigation and brand damage. As detailed above, automated options like X-rays and metal detectors can only identify certain foreign objects, leaving the rest to pass through untouched. Using superior spectral and spatial recognition capabilities, intelligent imaging technology can catch these objects and alert the appropriate employees or kickstart automated processes to fix the issue.

Mechanical Damage

Though it may not be put on the same level as pathogen detection, food freshness and foreign object detection, consumers put a premium on food uniformity, demanding high levels of consistency in everything from their apples to their zucchini. This can be especially difficult to ensure with agricultural products, where 10–40% of produce undergoes mechanical damage during processing. Increasingly complicated supply chains and progressively more automated production environments make delivering consistent quality more complicated than ever before.

Historically, machine vision systems and spectroscopy have been implemented to assist with damage detection, including bruising and cuts, in sorting facilities. However, these systems lack the spectral differentiation to effectively evaluate food and agricultural products in the stringent manner customers expect. Methods like spot spectroscopy require over-sampling to ensure that any detected aberrations are representative of the whole item. It’s a time-consuming process.

Intelligent imaging uses superior technology and machine learning to identify mechanical damage that’s not visible to humans or conventional machinery. For example, a potato may appear fine on the outside, but have extensive bruising beneath its skin. Hyperspectral imaging can find this bruising and decide whether the potato is too compromised to sell or within the parameters of acceptability.

Intelligent imaging can “see” what humans and older technology simply cannot. With the ability to be deployed at a number of locations within the food supply chain, it’s an adaptable technology with far-reaching applications. From drones measuring crop health in the field to inline or end-of-line positioning in processing facilities, there is the potential to take this beyond factory floors.

In the world of quality assurance, where a misdiagnosis can literally result in death, the additional spectral and spatial information provided by hyperspectral imaging can be utilized by food processors to provide important details regarding chemical and structural composition previously not discernible with rudimentary systems. When companies begin using intelligent imaging, it will yield important insights and add value as the food industry searches for reliable solutions to its most serious challenges. Intelligent imaging removes the subjectivity from food quality assurance, turning it into an objective endeavor.