In order to ensure that a food testing laboratory maintains a quality management system that effectively manages all aspects of laboratory operations that affect quality, there are numerous records, reports and data that must be recorded, documented and managed.

Gathering, organizing and controlling all the data that is generated, managed and stored by food testing laboratories can be challenging to say the least. As the ISO Standards and regulatory requirements for food testing laboratories evolve, so does the need for improved quality data management systems. Historical systems that were very efficient and effective 10 years ago, may no longer meet the demanding requirements for ISO 17025 certification. One way to meet the challenge is to turn to automated solutions that eliminate many of the mundane tasks that utilize valuable resources.

There are many reasons for laboratories to seek this certification, including to enhance reputation, gain a competitive advantage, reduce operational costs, and meet regulatory compliance goals. A major advantage for food testing laboratories to obtain ISO 17025 Certification is that is tells prospective clients that the laboratory has a strong commitment to quality, and they hold the certification to prove it. This certification not only boosts a laboratory’s reputation, but it also demonstrates an organization’s commitment to quality, operational efficiency and management practices. Proof of ISO 17025 Certification eliminates the need for independent supplier audits, because the quality, capability and expertise of the laboratory have been verified by external auditors. Many ISO Certified laboratories will only buy products (raw materials, supplies and software) and services from other ISO-certified firms so that they do not need to do additional work in qualifying the vendor or the products.

There are many areas in which a LIMS supports and promotes ISO 17025 compliance. Laboratories are required to manage and maintain SOPs (standard operating procedures) that accurately reflect all phases of current laboratory activities such as assessing data integrity, taking corrective actions, handling customer complaints, managing all test methods, and managing all documents pertaining to quality. In addition, all contact with clients and their testing instructions should be recorded and kept with the job/project documentation for access by the staff performing the tests/calibrations. With a computerized LIMS, laboratory staff can scan in all paper forms that arrive with the samples (special instructions, chain of custody (CoC), or any other documentation). This can be linked to the work order and is easy assessable by anyone who has the appropriate permissions. The LIMS provides extensive options for tracking and maintaining all correspondence, the ability to attach electronic files, scanned documents, create locked PDFs of final reports, COAs (Certificate of Analysis), and CoCs.

Sample Handling and Acceptance

Laboratories are required to have a procedure that defines all processes that a sample is subjected to while in the possession of the laboratory. Some of these procedures will relate to sample preservation, holding time requirements, and the type of container in which the sample is collected or stored. Other information that must be tracked includes sample identification and receipt procedures, along with acceptance or rejection criteria at log-in. Sample log-in begins and defines the entire analysis and disposal process, therefore it is important that all sample storage, tracking and shipping receipts as well as sample transmittal forms (CoC) are stored, managed and maintained throughout the sample’s analysis to final disposal. To summarize, the laboratory should have written procedures around the following related to sample preservation:

- Preservation

- Sample identification

- Sample acceptance conditions

- Holding timesShipping informationStorage

- Results and Reporting

- Disposal

The LIMS must allow capture and tracking of data throughout the sample’s active lifetime. In addition, laboratories are also required to document, manage and maintain essential information associated with the analytical analysis, such as incubator and refrigerator temperature charts, and instrument run files/logs. Also important is capturing data from any log books, which would include the unique sample identifier, and the date and time of the analysis, along with if the holding time is 72 hours or less or when time critical steps are included in the analysis, such as sample preparations, extractions, or incubations. Capturing the temperature data can be automated such that the data can be directly imported into the LIMS. If there is an issue with the temperature falling outside of a range, an email can automatically be spawned or a message sent to a cell phone to alert the responsible party. Automation saves time and money, and can prevent many potential problems via the LIMS ability to import and act on real-time data.

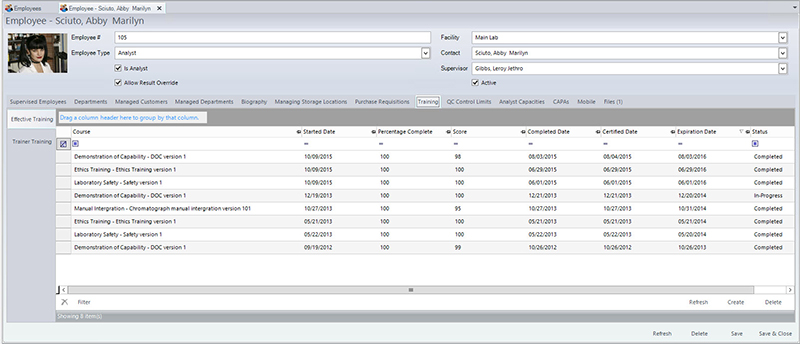

If any instrumentation is used in the analysis, the following information must also be recorded in the instrument identification (to ensure that it is in calibration, and all maintenance and calibration records are current), operating conditions/parameters, analysis type, any calculations, and analyst identification. In addition to analyst identification, laboratories must also keep track of analyst training as it relates to their laboratory functions. For example, if an analyst has not been trained on a particular method or if their certification has expired, the LIMS will not allow them to enter any result into the LIMS for the method(s) that they have not been trained/certified to perform. The LIMS can also send automated alerts when the training is about to expire. Figure 1 shows a screen in the LIMS that manages training completed, scheduled, tests scores, and expiration dates of the training, along with the ability to attach any training certificates, exams, or any other relevant documentation. Laboratory managers can also leverage the LIMS to pull reports that compare analyst work quality via an audit report. If they determine that one analyst has a significant amount of samples that require auditing, they can then investigate if there is a possible training issue. Having immediate access to data allows managers to more rapidly identify and mitigate potential problems.

Another major area that a LIMS can provide significant benefit is around data integrity. There are four main elements of data integrity:

- Documentation in the quality management system that defines the data integrity procedure, which is approved (signed/dated) by senior management.

- Data integrity training for the entire laboratory. Ensures that the database is secure and locked and operates under referential integrity.

- Detailed, regular monitoring of data integrity. Includes reviewing the audit trail reports and analyzing logs for any suspicious behavior on the system.

- Signed data integrity documentation for all laboratory employees indicating that they have read and understand the processes and procedures that have been defined.

The LIMS will enhance the ability to track and manage data integrity training (along with all training). The LIMS will provide a definition of the training, the date, time, and topic (description); instructor(s); timeframe in which the training is relevant, reminders on when it needs to be repeated; along with certifications, quiz scores, copies of quizzes, and more. With many tasks, the LIMS can provide managers with automated reports that are sent out at regular time intervals, schedule training for specific staff, provide them with automatic notification, schedule data integrity audits, and to facilitate FDA’s CFR 21 part 11 compliance (electronic signatures). The LIMS can also be configured to automatically have reports signed and delivered via fax or email, or to a web server. The LIMS manages permissions and privileges to all staff members that require access to specific data and have the ability to access that data, along with providing a secure document control mechanism.

Laboratories are also required to maintain SOPs that accurately reflect all phases of current laboratory operations such as assessing data integrity test methods, corrective actions and handling customer complaints. Most commercial LIMS provide the ability to link SOPs to the analytical methods such that analysts can pull down the SOP as they are doing the procedure to help ensure that no steps are omitted. Having the SOPs online ensures that everyone is using the same version of the locked SOPs, which are readily available and secure.

Administrative Records, Demonstration of Capability

Laboratories are required to manage and maintain the following information on an analyst working in the laboratory: Personal qualifications and experience and training records (degree certificates, CV’s), along with records of demonstration of capability for each analyst and a list of names (along with initials and signatures) for all staff that hold the responsibility to sign or initial any laboratory record. Most commercial LIMS will easily and securely track and manage all the required personnel records. Individuals responsible for signing off on laboratory records can be configured in the LIMS to not only document the assignment of responsibility but also to enforce it.

Reference Standards and Materials

Because the references and standards that laboratories use in their analytical measurements affect the correctness of the result, laboratories must have a system and procedures to manage and track the calibration of their reference standards. Documentation that calibration standards were calibrated by a body that can prove traceability must be provided. Although most standards are purchased from companies that specialize in the creation of reference standards, there are some standards that laboratories create internally that can also be traced and tracked in the LIMS. Most commercial LIMS will also allow for the creation, receipt, tracking, and management of all supplies in an inventory module, such that they document the reference material identification, lot numbers, expiration date, supplier, and vendor, and link the standard to all tests to which it was linked.

The ISO 17025 Standard identifies the high technical competence and management system requirements that guarantee your test results and calibrations are consistently accurate. The LIMS securely manages and maintains all the data that supports the Quality Management System.

Key advantages of food testing laboratories that have achieved ISO 17025 Certification with a computerized LIMS that securely and accurately stores all the pertinent data and information:

- Proof of ISO 17025 Certification eliminates the need for supplier audits, because the quality, capability and expertise of the laboratory have been demonstrated by the certification.

- Knowledge that there has been an evaluation of the staff, methods, instrumentation and equipment, calibration records and reporting to ensure test results are valid.

- Verification of operational efficiency by external auditors that have validated the quality, capability and expertise of the laboratory.

- Defines robust quality controls for the selection and authentication of methods, analyzing statistics, controlling and securing data.

- Clearly defines each employee’s roles, responsibilities and accountability.

- Confidence that the regulatory and safety requirements are effectively managed and met in a cost efficient-manner.