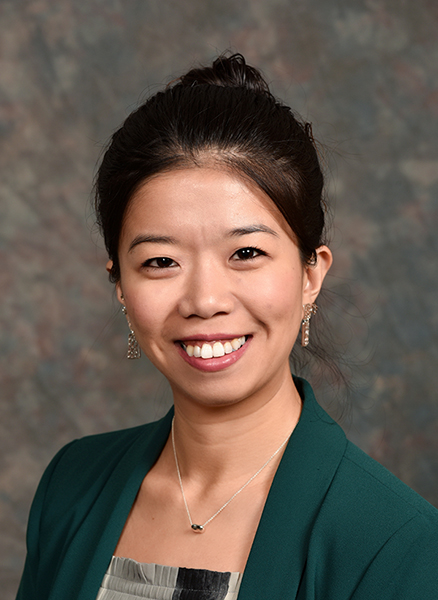

It’s always a pleasure to speak with LeAnn Chuboff, vice president of technical affairs at SQFI. On a cozy sunny afternoon, I chatted with her for more than an hour, and a lot of memories from when we worked together came back. Once again, it was another inspiring conversation.

LeAnn considered her sister as the first mentor who inspired her to take the food industry as her career path. When they were kids, they always visited test kitchens such as Betty Crocker. LeAnn found it fascinating to see how foods were made and developed. So when she went to Iowa State University, she pursued a bachelor’s degree in food science. After graduation, LeAnn took her first job as a food microbiologist, where she found her career. She liked the science and the mission in the food safety industry. During her career, LeAnn has worked for multiple food manufacturers, foodservice operations, the National Restaurant Association, and now is with FMI.

“I find it so fascinating to see the progress we have made in food safety since I started in this industry. I find us all so passionate with our purpose.” she said, adding how she persevered through her career when there were difficulties and challenges. “There will always be difficult decisions, but if you stick with your vision, mission and purpose, then those decisions will be made for you.”

During the interview, we spent some time discussing communication, how to get your voice heard, and how to effectively communicate. LeAnn provided some of her insights, although she said she is still working and learning on it.

- Listen; not ‘pretend’ listening but actually hear from your audience to understand what they are saying and their needs.

- Understand the problem before coming up with the solution. We all have great ideas but it’s always important to identify the problem we are trying to solve.

- Prepare a recommendation on a path forward. When you speak up and address a problem, try and have a recommendation on how to proceed.

At the end of the interview, I asked LeAnn whether she would do anything differently if the clocks turned back to right after her graduation from Iowa State. LeAnn’s answer was a solid no. She likes her career path. When she looks back now with her 30+ years’ experience and how she got to where she is currently, she has enjoyed every step. All the ups and downs through all her experiences have made her who she is today. “I do not think I would change anything, but I would give one piece of advice to my younger self: Be more open minded.”

“I believe there are glass ceilings in some areas, but it is cracking—it’s progress. We are all talented individuals, and we belong at the executive table. ” – LeAnn Chuboff

Melody Ge: Why do you prefer the food safety industry?

LeAnn Chuboff: I like the people and the working environment. There are so many opportunities. Like for myself, first, I was a food microbiologist working in a plant, then I managed a QA department where I think training and lab management are needed. Then, I was exposed to auditing when I was managing suppliers. There are a lot of open doors and opportunities of what you can do in this industry.

Ge: Do you have any tips for females who are working towards an executive position?

Chuboff: Aren’t you feeling sad that we are still talking about this? We, as women, have provided our points, and we are all talented individuals. We belong in this place, the executive team. We also belong in the environment. I think we need to recognize our talents and embrace ourselves. We bring valuable input to business. Second, we have to surround ourselves with people who are going to challenge us, encourage us, and provide us with the criticism that will help us grow and develop. No matter where we are in our professional career, we have to keep moving and learning, and make sure we know we belong.

Ge: I completely agree. I always think female/male is a personality. Individuals shall be seen objectively, when we work, we all have two sides, sometimes the male personality is stronger, sometimes, the female personality is needed. Do you believe in a glass ceiling, by the way?

Chuboff: I do believe that there is a glass ceiling in some industries and regions, but it’s cracking, and that includes in the food safety industry. However, I am very fortunate to work at where there are many examples of strong women in executive positions. We’ve made progress, but it takes time. I do believe we are in a unique environment where men recognize the talents of women; women recognize the talents of men. Four or five years ago, there were more ceilings, with more discussions revealed—it’s definitely shattering now

“As a leader, always treat people, all people, as I would like to be treated or how I wish I was treated.” – Chuboff.

Ge: There are always discussions about work-life balance. What is your vision of achieving balance?

Chuboff: To be honest, I have to say I am not good at this one, but I am trying my best. My best advice is to commit time for your family and personal life. For professional women, it’s not easy as it sounds to flip that switch, but we need to have the switch so we can turn off work mode. Especially with working from home, it always feels like we’re working. My other piece of advice is, don’t be afraid to ask for help. I think a lot of times, we feel like we are showing our vulnerabilities when we ask for help. Actually, we’re not! Asking for help doesn’t mean you are weak; asking for help can actually help you or the employer to balance resources.

Ge: Besides what you have shared today, if you could give one last tip for young female professionals who are entering the career or during the transition of their career, what would that be?

Chuboff: One thing I believe is that as long as you always represent who you are, and remain genuine with the expertise you have, you will shine!