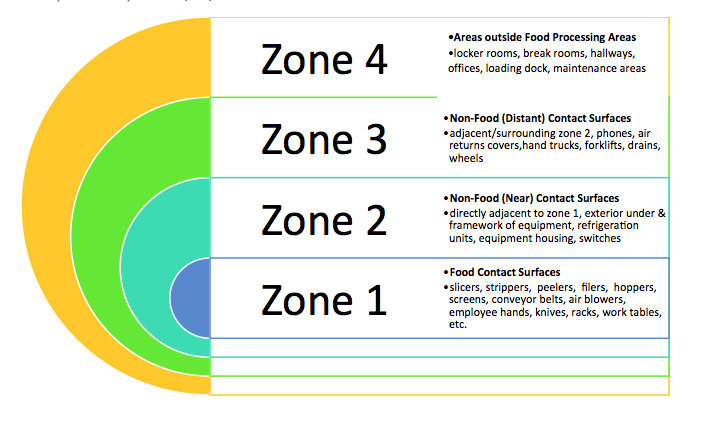

There are several ways in which pathogens can enter a food processing facility. Once inside, pathogens are either temporary visitors that are removed using cleaning and disinfection methods, or they can persist in sites such the floor or drains and require a more intense remediation process. As food processors take on the responsibility to prevent product adulteration in facilities, setting up and maintaining an environmental monitoring program (EMP) is critical. An effective EMP helps a company manage and potentially reduce operational, regulatory and branding reputation risks.

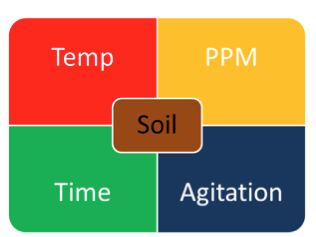

Establishing an EMP begins with identifying and documenting potential pathogen sources in all physical areas (including raw materials, storage and shipping areas) and cross-contamination vectors (employees, equipment, pests, etc.). These areas and vectors should be surveyed, controlled and when possible, eliminated. Implementing effective controls, including microbiological sampling of high-risk areas, should be part of the program. Sampling for pathogens or indicator microorganisms in food contact areas during production is also important. Additionally, the EMP elevates the awareness of what is happening in the plant environment and helps companies measure the efficiency of their pathogen-prevention program—for example, it is not only critical to test for pathogens, but also for the overall effectiveness of cleaning and sanitizing procedures. Both procedures are necessary and must be properly executed to reduce microorganisms to safe levels. The goal of a cleaning process is to remove completely food and other types of soil from a surface. Since soils vary widely in composition, no single detergent is capable of removing all types. In general, acid cleaners dissolve alkaline soils (minerals) and alkaline cleaners dissolve acid soils and food wastes. It is for this reason that the employees involved must understand the nature of the soil to be removed before selecting a detergent or a cleaning regime. The cleaner must also match with the water properties and be compatible (i.e., not corrosive) with the surface characteristics on which it will be applied. However, not only the correct choice of agent is necessary for an optimal result; it should be coupled with a mechanical action, an appropriated contact time and correct operating temperature. As the combination of these parameters is characteristic to each process, it becomes essential to verify effectiveness through sampling. Finally, cleaning is closely related to sanitation, because it can’t be sanitized what hasn’t been previously cleaned.

| “Not Your Grandfather’s Environmental Monitoring Program Anymore”: Learn more about this important topic at the 2016 Food Safety Consortium | EVENT WEBSITE |

The Association of Official Analytical Chemists defines sanitizing for food product contact surfaces as a process that reduces the contamination level by 99.999% (5 logs). Sanitation may be achieved using either heat (thermal treatment) or chemicals. Hot water sanitizing is commonly used where immersing the contact surfaces is practical (e.g., small parts, utensils). Hot water sanitizing is effective only when appropriate temperatures can be maintained for the appropriate period of time. For example, depending on the application, sanitation may be achieved by immersing parts or utensils in water at 770 C to 850 C for 45 seconds to five minutes. The advantages of this method include easy application, availability, effective for a broad range of microorganisms, non-corrosive, and it penetrates cracks and crevices. However, the process is relatively slow, can contribute to high energy costs, may contribute to the formation of biofilms and may shorten the life of certain equipment parts (e.g., seals and gaskets). Furthermore, fungal spores can survive this treatment.

Regarding chemicals, there is no perfect chemical sanitizer. Performance depends on sanitizer concentration (too low or too high is ineffective), contact exposure time, temperature of the sanitizing solution (generally, 210 C to 380 C is considered optimal), pH of the water solution (each sanitizer has an optimal pH), water hardness, and surface cleanliness. Some chemical sanitizers, such as chlorine, react with food and soil, becoming less effective on surfaces that have not been properly cleaned.

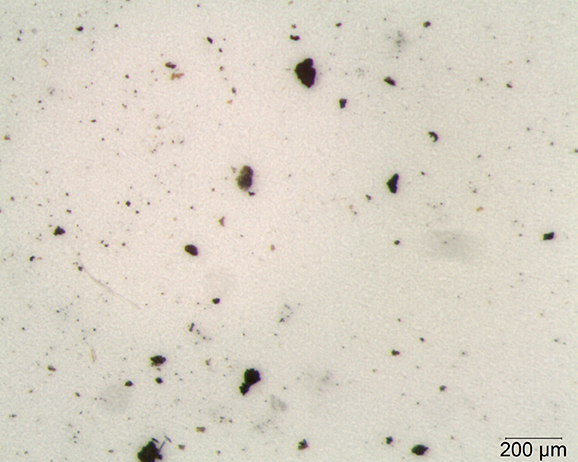

The effectiveness of a plant’s sanitation practices must be verified to ensure that the production equipment and environment are sanitary. Operators employ several methods of verification, including physical and visual inspection, as part of ongoing environmental hygiene monitoring programs. Portable ATP bioluminescence systems are widely used to obtain immediate results about the sanitary or unsanitary condition of food plant surfaces. ATP results should be followed up with more in-depth confirmation testing, such as indirect indicator tests and pathogen-specific tests. Indirect indicator tests are based on non-pathogenic microorganisms (i.e., coliform, fecal coliforms or total counts) that may be naturally present in food or in the same environment as a pathogen. These indicator organisms are used to assess the overall sanitation or environmental condition that may indicate the presence of pathogens. The principal advantages of using indicator organisms in an EMP include:

- Detection techniques are less expensive compared to those used for pathogens

- Indicator microorganisms are present in high numbers and a baseline can be easily established

- Indicator microorganisms are a valid representative of pathogens of concern since they survive under similar physical, chemical and nutrient conditions as the pathogen

However, indicator organisms are not a substitute for pathogen testing. A positive result indicates possible contamination and a risk of foodborne disease. It is recommended that samples be taken immediately before production starts, just after cleaning and sanitation have been completed when information regarding cleaning and sanitation are required. However, when sampling is conducted on surfaces previously exposed to chemical germicide treatment, appropriate neutralizers must be incorporated into the medium to preserve viability of the microbial cells.

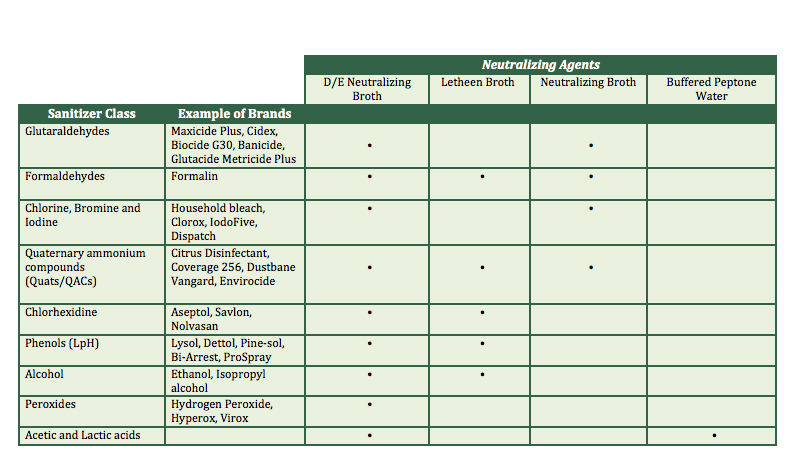

Neutralizers recommended for food plant monitoring include Dey-Engley neutralizing broth (DE), neutralizing buffer (NE), Buffered peptone water (BPW) and Letheen broth (LT) (see Table I). Most of these are incorporated into a support such as a sponge, swab or chiffon to neutralize the residues of cleaning agents and sanitizers that may be picked up during swabbing. The product should be selected based on the surface, the type of cleaning agents and the type of testing (qualitative or quantitative).

It is critical to verify that the chosen neutralizer has an efficient action against the used sanitizers. Table I show the most effective equivalence among the cleaning agents and the most common neutralizers.

For instance, if a quantitative method is to be used, it is very important to consider a neutralizing agent, such as the neutralizing buffer, that doesn’t support the bacterial growth.

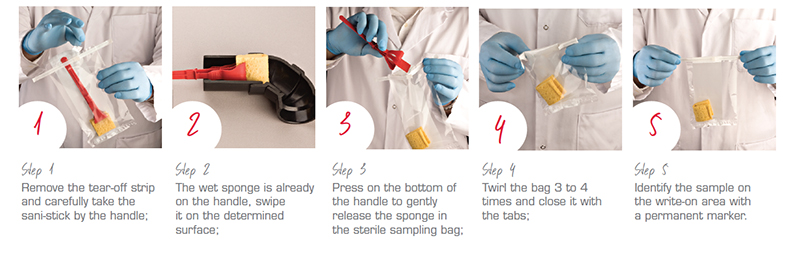

Finally the sponge is a very popular choice due to its versatility. Sponges are used for sampling equipment surfaces, floors, walls, work benches and even carcasses. They enable the sampling of large surfaces and the detection of lower levels of contamination at a lower cost of operation.

To summarize, environmental sampling is an important tool to verify sources of contamination and adequacy of sanitation process, helping to refine the frequency and intensity of cleaning and sanitation, identify hot spots, validate food safety programs, and provide an early warning of issues that may require corrective action. Over all, it provides the assurance that products being manufactured are made under sanitary conditions.