There is no question that we are in the midst of a unique time period in history. Technology is continuing to innovate at an increasingly rapid rate, which has led to drastic changes that affect nearly every corner of day-to-day life. From the way we find information to our food choices, technology is influencing our lives in new ways.

The Rise of the Internet

Mary Meeker, the venture capitalist who was dubbed the “Queen of the Internet” more than 15 years ago, has described the current Internet age as a period of reimagining. At the heart of this reimagining has been the rapid growth, maturity and adoption of the Internet and Internet-enabled technologies.

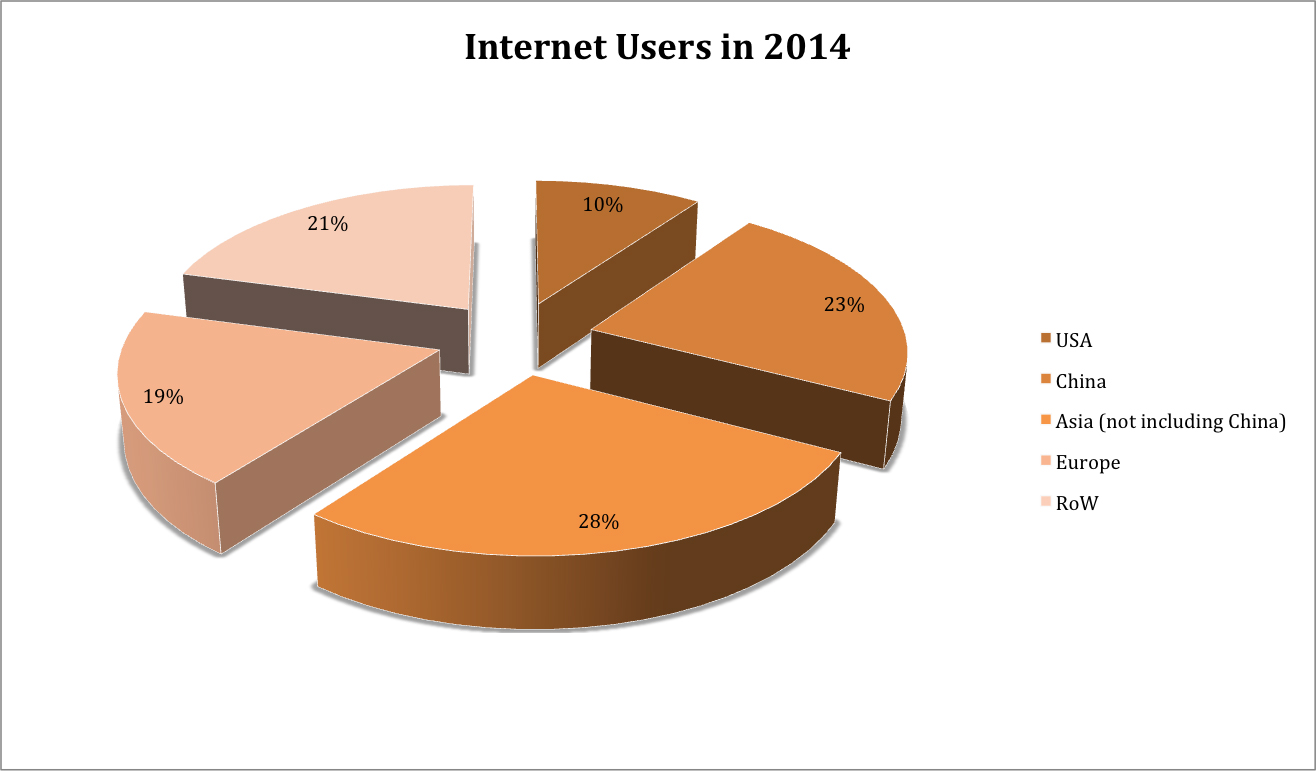

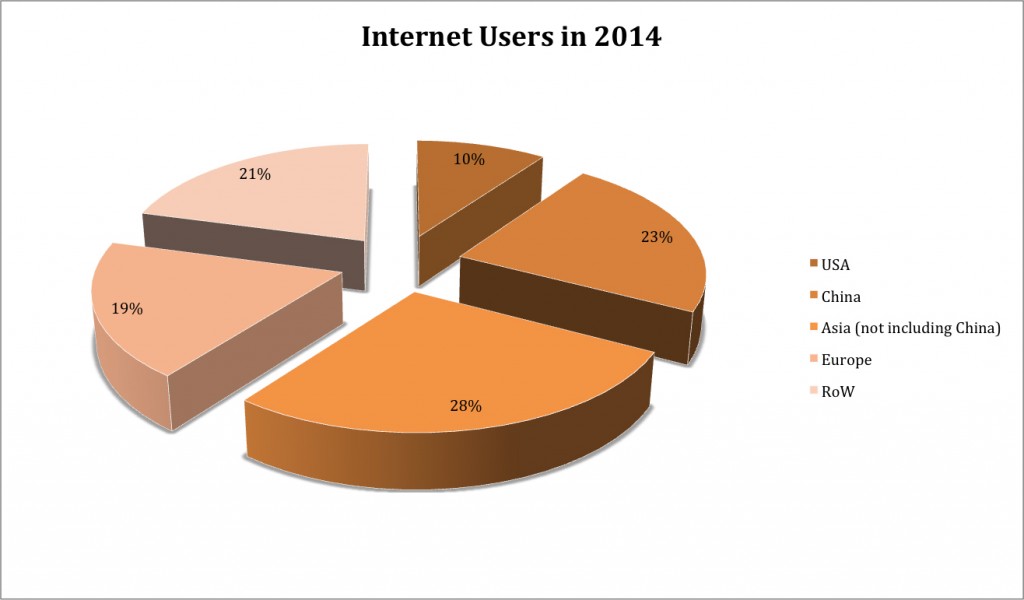

In her most recent 2015 research, Meeker published some fascinating statistics. The number of people online has ballooned more 80 times, from a user base of a mere 35 million in 1995 to a staggering 2.8 billion users in less than 20 years. This figure translates into nearly 40% of the total global population.

It hasn’t just been the volume of usage that has evolved radically. The nature by which those billions of users are signing online has also changed. It’s hard to believe that the original iPhone was released in 2007, less than 10 years ago. In that time, the mobile Internet has gone from a novelty to a necessity for many of us in our daily lives. This smartphone adoption has fueled Internet use and has drastically increased the ease with which consumers can get online.

Reimagining Communication and Compliance

The result of our new “always-on,” globally connected world (to borrow Meeker’s term) is a complete reimagining of communication. Consumers expect a velocity and volume of communication that the world has never before experienced. We now take for granted that we can reach friends, family and acquaintances anywhere in the world—at any time—in an instant. This has also drastically changed our expectations of business relationships.

Consumers in an ever-connected world have an expectation of availability and transparency of information from the brands with which they interact and the establishments they frequent. What this means for businesses is that customers expect to have a degree of access to business data that they’ve never asked for previously.

A tangible side effect of this desire for data transparency can be seen within the regulatory environment that organizations operate. Governments and regulatory bodies have increased their expectations of data access and availability over time, resulting in more stringent regulations across the board.

Research from Enhesa shows that the regulatory growth rate is nearly as staggering as Internet growth rates. According to the firm’s research, from 2007–2014 regulatory increases by region were as follows:

- North America: +146%

- Europe: +206%

- Asia: +104%

Impact on Food Safety: Consumer Engagement and Regulatory Growth

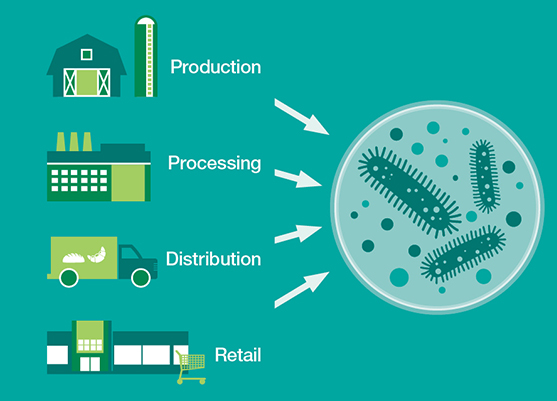

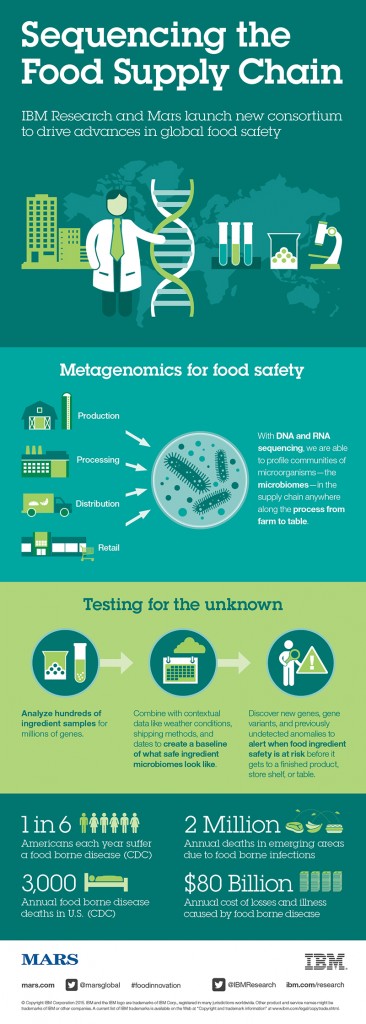

One particular area of regulatory growth has occurred within the food and beverage sector. Arguably no product category has a more direct impact on consumers than food, as it literally fuels us each day. It’s no wonder that in an environment of increasing regulations and more empowered consumers that food quality and food safety are under increased scrutiny.

In today’s environment, it becomes much more challenging to brush aside product recalls and food safety incidents or bury these stories in specialized media. The latest news is not just a fleeting negative headline. In a worst-case scenario these incidents are viral, voracious and more shareable than ever before. From Listeria outbreaks to contaminated meat to questionable farming practices—when fueled by the Internet, the negative branding impact of these stories can be staggering. Consumers are paying attention and engaging with these stories—for example, during a Listeria or Salmonella outbreak, online searches for these terms significantly rise.

The rise of hyper-aware consumers has had a measurable impact. As a result, governments have been quick to respond and have beefed up existing regulations for the food and beverage sector via FSMA and GFSI.